September 8 - 14, 2013: Issue 127

Shelagh Bokenham

On Saturday 12th of October, 2013 Shelagh Bokenham will be part of the ‘Say It With Music’ concert at St Marks, Avalon with special guests Soloist Greg Van Struik accompanied by Krisitie Van Der Struik, all ably supported by The Singers For Joy choir. This wonderful concert will be an entry by donation affair to raise funds for one of this church’s missions, the Malami school in Africa.

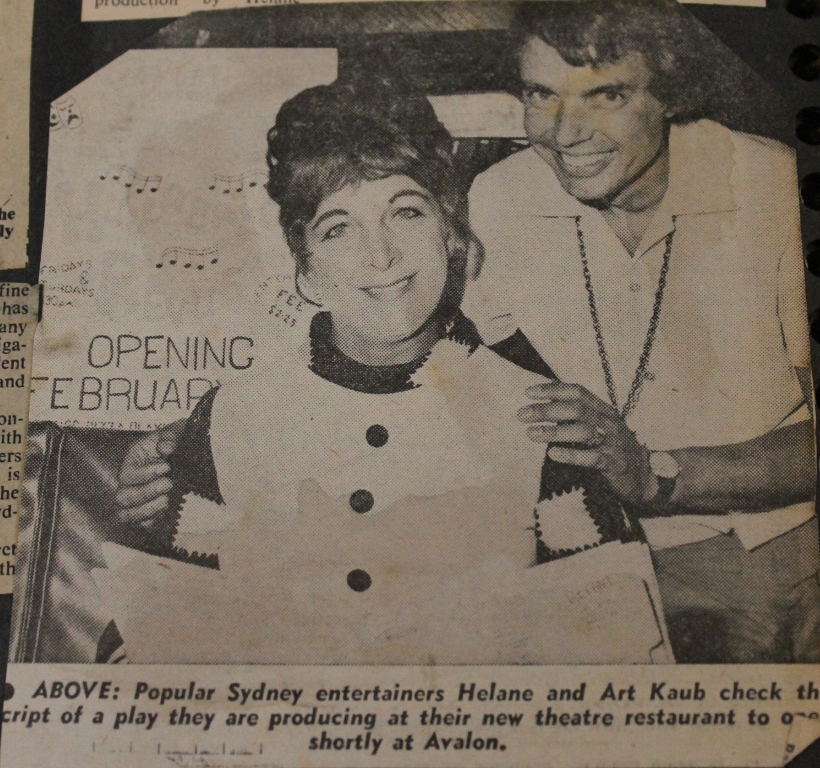

Many people will remember Shelagh from the Pizza Playhouse theatre restaurant opened by Helane and Art Kaub in the upstairs area of Barefoot Boulevarde in 1970 or as a vital member of the New Athenians, or the St Marks Players but the story, as with all of us, is much bigger and deeper then that.

Where and when were you born?

I was born in England, I’m a Navy brat. Our family has been in the Navy for generations –my nephew has been doing the family tree and has gotten to the 11th century and we’re all still in the Navy. My mother was in the Navy at Portsmouth Base – my father took one lot of the ships over to Dunkirk, we were right opposite France.

Shelagh with brother Kerrell

I grew up there during the war (WWII). I was 16 when we came to Australia. It was one of the worst winters we’d ever had and my mother said “that’s it, we’re going to Australia.”

They chose Australia primarily because of two people we met

during the war. During the war if you had ships coming in because they were

damaged, you also had sailors of all nationalities coming in too who would have

ten hours liberty or so on while the ships were being worked on (at the Naval

Dockyards – Portsmouth). People would take them home with them and feed them and

they slept on the floor, this is what you did then.

They chose Australia primarily because of two people we met

during the war. During the war if you had ships coming in because they were

damaged, you also had sailors of all nationalities coming in too who would have

ten hours liberty or so on while the ships were being worked on (at the Naval

Dockyards – Portsmouth). People would take them home with them and feed them and

they slept on the floor, this is what you did then.

Mum brought these two home and they were Australian. They rang a bell with us because, you know how in America they had that famous comic strip Dick Tracy, well in England they had one equally famous, Buck Ryan, and this fellow’s name was ‘Buck Ryan’, with his friend was Jimmy Green, who we used to call ‘Bluey’.

I said ‘why do you call him ‘bluey’?’ and he said “Don’t be silly, he’s got red flaming hair!”.

And I said, ‘what’s that got to do with it?’

He said “Everybody with flaming red hair is a ‘Bluey!’

We got to know them and they used to visit every time they did come into port because repairs were always being done there. When things were really bad mum would say, “Tell us about Australia.” And he’d pop his hat on the back of his head, I don’t know how they keep it there but he did, and then… ‘Ahhh now, Australia… and Sydney, now there’s a bloody beaut country…’.

Unfortunately they both went down on The Hood but, we never forgot that and mum said, Buck was right, we’re off to Australia and that’s what we did, just out of the blue, and I was about sixteen then.

So you came to Sydney?

Well, there was a delay, the post-war delays, and we also found that if you did have a job to go and speak the language then you didn’t get on very quickly but if you didn’t then you did, it was one of those times. We were nominated by a friend of mothers, Commander Kitchen, and of course by the time we got here he was at Northbridge, he was still a serving officer and had been posted to Melbourne. So there we were. We bought a business in Normanhurst because it had, if you’ll pardon the expression, ‘live-in premises’.

The premises in Normanhurst was three shops – grocery, library, mixed goods ironmongers. He knew business, dad was a very good businessman.

What did your dad do during WWII?

He was serving in an occupied job and was part of the Home Guard, and I don’t mean Dad’s Army – my mother was in the Navy, and all her side of the family were too – I mean, is there another Service? I remember doing relief (holiday) for my mother on the Eastern Queen at one stage, a Merchant Navy ship, and was the only woman on board.

Shelagh's father is the gentleman at front of picture - 1940

So how long did they have the business at Normanhurst?

At that time in Australia, post-war, you couldn’t get the goods. You couldn’t get the materials, everything was scarce. So we bided our time, and of course we delivered. In a short street at Bryan Avenue there were people we got to know very well and Tom Raywood, I’ll never forget him, he was an Aussie builder, and he said to dad – you don’t want to buy a house, you want to build it.

My father had always been very good with his hands, we’d always been sailing and he always built his own boats. And he said to Tom “Can I?” to which the answer was “of course you can, no problem, we’ll help you.”

So that’s what we did. Dad nearly died of shock when they burnt the Normanhurst block off, all we’d heard of Australia was ‘strike a match and you’ll get a bushfire’ ...so he was lighting these little fires and then putting them out, and Tom said “What do you think you’re doing?!” and he set fire to the whole block and my father nearly died…he said they were squatting there, rolling a cigarette and leisurely smoking it, just watching.

What was Normanhurst like then?

Thornleigh was completely in the bush, dad delivered to people there out on the track; there were no factories, none of that, it was completely in the bush. On a Saturday night we’d walk from Normanhurst to Hornsby to go to the pictures. Normanhurst was five shops, that was it. Our three on the corner, which was called ‘Martin’s corner’ and there was a butchers.

The biggest obstacle for me to begin with was the English language. I can remember someone asking me for six buckets and I gave him six galvanised buckets and he said “I wanted six buckets of ice-cream.”

We lived there for quite a while and then unfortunately my father died when he was quite young, only 52, it was all the stress and strain from the war. My brother married and his wife liked the house so my mother gave it to them and we came down here – I bought a place at Avalon.

How did you get into theatre? How old were you?

The first part I ever took was when I was one of the Babes in the Woods and I was about two years old. I was. I’m quite sure, a very precocious child, although some would called it ‘artistic whatsit’ but I was never happy being in the chorus, I went to dancing school because I wanted to do ballet and did so for about ten years before I twisted my knee and that was that, and I brought the house down because they put me without 30 other children in this dance routine. My father said, your uncle Richard and I were paralytic – we were holding up the wall, everybody noticed you.

We were all dancing around in a circle like this and every time I’d come to the front, (shows big smile) pulling this face to everybody – I was obviously a star at that time.

I did it off and on while at school too – I wrote plays and directed them and ended up School Captain, breaking rules all along the way.

Which school was this?

Well, then it was whichever school wherever you could get.

A lot of the schools had been bombed along with Portsmouth, which was bombed

very very heavily, but we ended up at Court Lane. I did a year-eighteen months

in a castle in Scotland in Dunoon, lovely place but the Scots didn’t take kindly

to all these Sassenachs coming in so we had to fight battles all the time. I

came back with a bit of an accent as a matter of fact. I have an ear for accents

and use them in plays all the time.

Well, then it was whichever school wherever you could get.

A lot of the schools had been bombed along with Portsmouth, which was bombed

very very heavily, but we ended up at Court Lane. I did a year-eighteen months

in a castle in Scotland in Dunoon, lovely place but the Scots didn’t take kindly

to all these Sassenachs coming in so we had to fight battles all the time. I

came back with a bit of an accent as a matter of fact. I have an ear for accents

and use them in plays all the time.

So you were sent away like so many children were in England?

They sent us away at first, then two things happened – we got separated, my brother and I, and we were more or less like twins so that didn’t work. So my grandmother said, look this is my war job, if we’re going to die then we’ll all die together so we came back from the evacuation. The evacuation wasn’t good for some – they’d machine gun the streets after school. You couldn't find your way home sometimes - the whole stret was ruble on either side, you couldn't recognise where you were. So we stayed at home and with our grandmother, whose house was in the same row as ours. When you got to go to school, as you didn’t always get to go you see, and mum would set lessons for those days, when she was there – she had a lot to do with the D Day landings and was often away. We were never children, none of us were. We were little adults.

Were you still I school when you came to Australia?

I’d finished off before we came out here. It’s hard to explain, but in England at that time, so many schools had been bombed and, as anybody will tell you, after a war, any war, the people to be are the ones who were conquered or lost because you rebuild their cities long before you get to your own. England and English people were on rations for ten years after the war finished…and rationing like people wouldn’t believe – you couldn’t get any elastic to pull your drawers up – you couldn’t get cotton. My father said “I can’t remember when I had a tail to my shirt.” You used to cut the tail off to line the collars and then fix the tail with flour sacks, whatever you had.

Dad sold the car before the war and we didn’t have another car until we came out here because if you could get the car you’d be darn lucky and if you did you couldn’t get the petrol. I have a giggle when it rains and children are run to school. We used to cycle through the snow, we just did it, we got on with it.

When we first came out here I wanted to do my nursing

training. We were told that my school passes, I had my certificate, the

equivalent of your leaving certificate, and I had matriculated, weren’t

sufficient. So I did a lot of swotting up.

When we first came out here I wanted to do my nursing

training. We were told that my school passes, I had my certificate, the

equivalent of your leaving certificate, and I had matriculated, weren’t

sufficient. So I did a lot of swotting up.

I went for the Nurses Entrance Exam and we had four hours to complete this and after an hour and a half I was just sitting there. One of the Examiners asked me if I couldn’t complete it and I said ‘I’ve finished.’

They told me afterwards that they couldn’t give me 100% - it was a composition, dictation, sums – not maths and a spelling bee – that was it. So I went into nursing then.

Did you have to stay on the premises ‘in quarters’?

Yes we stayed in quarters, 40 people in a Nissen Hut, with the university students raiding us every five minutes. I was at Prince Alfred to begin with and then, living at Normanhurst, I went to Hornsby. Hornsby then was very small, it only had one ward upstairs, which was called ‘Upstairs’. We used to have to carry the patients up from the theatre and then up the steps. It was a lovely hospital to work at.

Which area of nursing were you most interested in?

I was going into neurosurgery but then dad died and I had a mother to look after and Kerrell, my brother, was going into engineering and was in the wilds of Africa plugging his electric shaver into the nearest tree. I left the nursing because I had to be on something where I wasn’t on shifts.

I worked for Elizabeth Arden, I was one of their leading consultants. At one stage I worked on the Sundowners set as they were having problems with their makeup and the Elizabeth Arden range solved this.

ELIZABETH ARDEN AND DAVIES PHARMACY IN KINGSTON - Today and every day until Saturday next Elizabeth Arden's personal consultant offers appointments with as many as possible to give instruction in the expert use of these lovely cosmetics. Miss Bokenham will give a limited number of "make ups" free and without obligation. Learn to use Miss Arden's products in your own home. Make an appointment and seek Miss Bokenham's advice on the "care of the skin' —Davies Pharmacy at Kingston. ELIZABETH ARDEN AND DA VIES PHARMACY IN KINGSTON. (1959, November 10). The Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 - 1995), p. 18. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103106632

I was doing commercials and things like that as soon as I

got here and I’d joined Anthony Horderns ‘Hordernians’. On their fifth floor

they had a beautiful theatre and a society called the ‘Hordernians’ and I met a

director there – my name was changed to Shelagh Page. I did a lot of fashion

compering – some for Carla Zampatti – and then McDowell’s head-hunted

me.

I was doing commercials and things like that as soon as I

got here and I’d joined Anthony Horderns ‘Hordernians’. On their fifth floor

they had a beautiful theatre and a society called the ‘Hordernians’ and I met a

director there – my name was changed to Shelagh Page. I did a lot of fashion

compering – some for Carla Zampatti – and then McDowell’s head-hunted

me.

When I was working for Elizabeth Arden, McDowell’s were the first big retail store to move into the suburbs – they were a wonderful firm, a family firm, they had been in business for 75 odd years by then. Sir Frank McDowell ran the whole place, lovely people, lovely man, a real gent. So the McDowell’s started their first suburban store at Hornsby, everybody said they were mad, no one had moved out into the suburbs yet, just they did, and they came to me and said “we’ll offer you this.”

They hadn’t finished building it yet but asked me to join them because they said, you know the area, we don’t. And they’d go up to check on the works every two or three days and asked me ‘what do you think?’ and I said, well, the aisles for one thing are not wide enough. And he’d say, well they’re as wide as the city ones – to which I answered, don’t think city-Hornsby, think Hornsby – Berowra. At that time you had hundreds and hundreds of Italians and Lebanese out there working on the railways and they all have children – and this was before they had twin strollers – the aisles need to be wider to accommodate families shopping – so I was advising them all the way through this. When it went up it was the number one store in suburban retail. They rebuilt it later on but it was still number one, it took more money then anybody.

Once it was opened I did modelling as well in this store.

How was your theatre interests fitting in at this time?

You do it at night and on the weekends; I belonged to theatre groups and the Hordernians for a while and then I was hunted by the Chatswood Musical Society for Oklahoma. That was the first musical I did.

My mother Muriel Guy was a concert pianist before she was married, and she said, you can act, you can write, you can dance – why do you want to do singing when you can’t sing? Red flag to a bull really – so I sang and that was it.

I remember another one where they reviewed me – they wanted a torch singer, so I sat on this piano and sang this song about five keys lower then it should be …and luckily it was a big hit but I have since learnt to sing properly!

Then I discovered you don’t have true pantomimes out here so I wrote pantomimes and we did those too – where principal boy is a girl and there’s a demon king and the dame is a fellow and there’s always a scene where he takes his corsets off which are closed with big brass bolts. Pantomime is a certain style – out here they put pop singers in and this is not the answer, the principal girl must be a boy with a good pair of gams (legs). There’s a lot of traditional things incorporated. Then I wrote Robin Hood’s Wedding – I played Robin Hood and I married the sheriff !

People will remember the Chatswood Musical Society, not to be confused with Willoughby – Willoughby was not in it then – Chatswood had been going for years before then – very successfully. When Willoughby started up we’d help them out – lend them costumes and things like that because theatre people are like that. I was with them even after I moved to Avalon – there wasn’t so much traffic then and they were a lovely group.

Then of course, when I moved to Avalon, I formed my own society – first off we were called The New Athenians, and then when Lloyd Bennet was the minister at St Marks, we took over Keen Hall and rehearsed there and would do at least three shows a year of six performances each and after expenses we gave the money to the church. We then changed our name to the St Mark’s Players. We were there for years and highly successful until I went to Tamworth.

When did you move to Avalon?

I can’t remember the year but I was 23. Avalon hasn’t

changed that much since then – people here resist that kind of thing. Where we

were in Ryan avenue at Normanhurst, we were number 14 and we were at the end of

the street, so it only had a few houses there. One of those living in this short

street was whom we bought the business from and we became firm friends, and they

were only too happy, and that was the thing, they wanted you to like their

country, and they said “On a Sunday we all go down to a beach, we go to Collaroy

beach.”

I can’t remember the year but I was 23. Avalon hasn’t

changed that much since then – people here resist that kind of thing. Where we

were in Ryan avenue at Normanhurst, we were number 14 and we were at the end of

the street, so it only had a few houses there. One of those living in this short

street was whom we bought the business from and we became firm friends, and they

were only too happy, and that was the thing, they wanted you to like their

country, and they said “On a Sunday we all go down to a beach, we go to Collaroy

beach.”

We had an old truck which went with the business which we called ‘Leaping Lena’ , it was a 1938 Chevy or something like that which was falling to bits – we’d get her chugging along and she’d get up to the top of a hill and you’d have to stop and let her have a blow. We had her for years, she was wonderful.

The ritual was everyone in the street would get into the truck or Tom Raywood’s car and we’d all go to Collaroy and then on the way back we’d stop at this little shop just outside of Narrabeen and everyone would have a bag of chips. That’s what you did then.

Because of these visits we’d also drive around here; my father loved this country and there was this house there that had the chimney breast outside and it was all colours and dad used to call it ‘April Cottage’ and he’d say ‘one day, we’ll have an April cottage of our own’…and he always wanted to come here. I was a swim freak, and my brother loved the beach too.

When my brother married they bought a place at 18 Elaine avenue, and my sister-in-law preferred a more metropolitan lifestyle then the beach lifestyle, and much preferred the house at Normanhurst. So we did a house swap; they had Normanhurst and we had Elaine Avenue. This was a solidly built house but had been built to be a weekender and had many kinds of paints inside, which is what you did then with what was available. It had a dark blue on two walls, the other one was pink and the ceiling was rancid butter yellow.

I took that place apart and put it back together – we had a piano of course. Every party I ever had we ended up with people around the piano singing. When I was first down here Maureen Stiles and I would load my piano onto the back of a truck and go all around the area singing Carols.

I sold the place in Avalon, bought a place in Palm Beach and fixed that up then sold that and then bought at the corner of Wollstonecraft and paid out that place completely. My mother then got Alzheimer’s very badly and had other health issues. She had a younger brother who had come out here and moved to Tamworth and I took mum up there for a visit and she wanted to go there – that was her younger brother.

For her it was very good. It’s a lovely place Tamworth and theatrically, for me, I’ve never done so well in all my life and am now a Life Member of the Tamworth Dramatic Society and the Musical Society and had my own theatre there which was a 100 year old church. I was in Tamworth for around 18 years. I got some television commercials, which don’t pay as well as they do in Sydney of course, and was looking after mum full time too.

For the last ten years, there was a theatre restaurant there, Riley’s, and he wanted to have a theatre restaurant like the good old days music halls, they used to be on the ABC – they came from England. He did the décor, got in touch with Bill Gleeson who was extremely well known then, and Bill couldn’t do it but said ‘I know someone who could do it for you for the first three months and then I’ll be available.”

I got my special people together – Trish, who is a beautiful singer, and Max – audiences adored him, and Ken and I explained to them, they were all top-flight amateurs, that I had this for three months and if I got it the way I wanted to get it it may be longer then that. I explained that as professionals they would be doing 52 shows a year, two hour shows, that will involve a lot of singing and a lot of costume changes plus, on top of that, you’ve still got to rehearse two times a week; you have to turn the quarters of the shows over and so it’s changing all the time. You think you know what it is going to take, but I’m telling you now, you don’t.

What advice would you give to anyone who wants to get into theatre now?

The common thing is, particularly if they’re young people, is that people may say ‘they’re born actors or actresses’ and I’m sorry, there’s no such thing. People are born with talent but the other…what it requires to make a good actor or actress are three things: discipline, discipline and discipline.

I’ve had some people, extremely talented, whom I wouldn’t touch with a barge pole – they had no discipline. In themselves they are funny and the audience loves them, they upstage everybody they’re with – but it’s a team job out there and you have to work hard.

This group did and they loved it – we were performing every Saturday night. They were good and they got better and better and did things they thought they never could do. We travelled the show – made sets and cut them in half so they could load them into this trailer, and we went all over the place.

What is the best thing about being involved in theatre for you?

There’s nothing like it.

There’s no business like show business?

We’re doing that number in October! When people ask me that

there’s one huge factor – I have worked with all these women – gorgeous, much

better singers then me, and they’ve all said to me, and I don’t take this as a

boast, I take this with great gratitude, ‘what have you got that we don’t? - I

have a better voice then you, I look better then you, but it’s you they fall

over’.

We’re doing that number in October! When people ask me that

there’s one huge factor – I have worked with all these women – gorgeous, much

better singers then me, and they’ve all said to me, and I don’t take this as a

boast, I take this with great gratitude, ‘what have you got that we don’t? - I

have a better voice then you, I look better then you, but it’s you they fall

over’.

My answer was and still is – LOVE Your Audience ! Love them.

I have never got over, in all the years I’ve been doing this, the sound of people applauding you and knowing – they want me.

You have got to love them – when I do the shows here, I don’t have the houselights completely out, I want to see their faces – I work to their faces – I say all sorts of things, I don’t know what I’m going to say.

There are a lot of unwritten rules in theatre of course – you never mention the name of that play about the Scotsman…you can say it but I mustn’t.

King Lear or Macbeth?.. oh Macbeth, yes…MacDuff

Yes! It’s bad luck to.

Why do people say ‘break a leg’? How is that lucky, telling someone to break their leg?

That is a comical good luck – of course it has gotten a little distorted. The person who is supposed to say it is of course the understudy – there is a story that goes with that originally of course – a very famous person got her break because of that – and Carol Channing was the star and her understudy said ‘break a leg’ and she did. The understudy had to go on, it was the beginning of the run, and the understudy was Shirley MacLaine, and that gave her her start.

There’s other things – you don’t whistle in a dressing room. You don’t put a hat on the table. You mustn’t quote form the Scottish play – that thing about kindness – you must go outside the theatre, turn around three times and then come back in. I don’t observe all of them but I do observe most of them because you will be surprised how many people who work in theatre are superstitious – I’m not but as I say, I don’t name the Scottish play as it affects other people.

After all you’ve done, nursing, helping people, open big stores, commercials, theatre, musical theatre, looking after your mum; what is your favourite thing?

I’m an actress who sings, and director – that’s what I enjoy most. At present of a Tuesday afternoon, at Newport Civic centre, we’re very fortunate to have a lady named Diana Arfaras who is a professional and I’m just loving it.

What is your favourite place in Pittwater and why?

Avalon of course; because I love the way people will just come to the back door, as they did with me and make the tea on thew way in – or somebody you haven’t seen for six months will just turn up and say ‘where’s my coffee?’ I love the informality. I love the people, the people we have here; as I said the U3A choir – they’d never done anything outside, and I said I want you to – you’ve got to have a goal – it makes it all better, something to aim for. What makes you so good is all of you, the collective, and we can’t afford to not have one of you there. It’s all of you singing together that makes you work.

What is your ‘motto for life’ or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

Copyright Shelagh Bokenham, 2013.