The Girl Who Stole Stockings by Elsbeth Hardie

Each time we delve into these records a story of family evolves as we collate more material and you do, quite honestly, fall a little in love with everyone you research: you feel sadness and even shed a tear when a mother loses a child, or children lost a mother during the hundreds of years when women did die in childbirth. You wonder what happened to fathers lost at sea when no records and no wreckage can point to their way they were lost and where they were lost.

Family Histories are a fascinating way of finding out more about where we came from, and in this instance, when Australia was first becoming a European colony and not so many people were here, a wonderful way of illustrating how entwined with the history of a place the footsteps of people may be and how this brings out what was happening and allows us insights into what people may have thought and how they reacted to the place they found themselves in.

Family Histories are a fascinating way of finding out more about where we came from, and in this instance, when Australia was first becoming a European colony and not so many people were here, a wonderful way of illustrating how entwined with the history of a place the footsteps of people may be and how this brings out what was happening and allows us insights into what people may have thought and how they reacted to the place they found themselves in.

What was invisible become visible.

A recent visitor to Manly, Elsbeth Hardie, spoke to us recently regarding searching for her great, great, great grandmother, Susannah Noon, work that took over seven years to trace those small threads and see how they wove together. In doing so she has produced a work, The Girl Who Stole Stockings, that traces the lives of women transported on the convict ship Friends which arrived in Sydney on October 10th, 1811.

Unlike other transports, virtually no records of the Friends’ voyage remain. In their absence, Ms Hardie has had to plough through early court records, colonial files and family history accounts to piece together what happened to the women after they arrived.

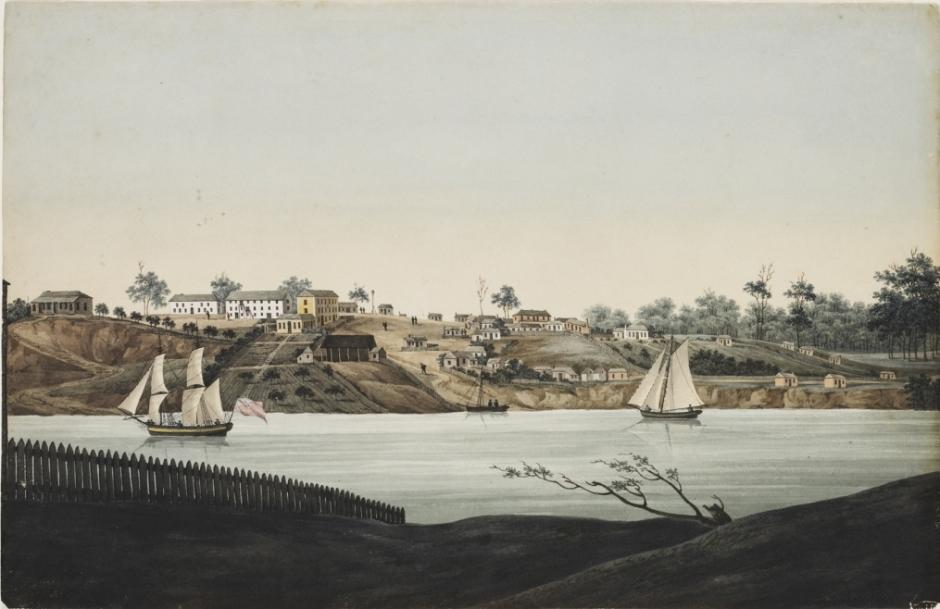

On Thursday arrived the Friends transport, Capt. Ralph, from England, having on board 100 female prisoners, all of whom are arrived in a healthy state.SHIP NEWS. (1811, October 12 - Thursday). The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article628340

While most of the women transported on Friends had been convicted of theft, there was also a young murderer on board and a woman who had tried to kidnap a child, both rare crimes among the women who were transported to New South Wales; more usually they earned a death sentence.

Elsbeth's book is a connection with the present too. Including Susannah, at least 23 women from the Friends had children in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). Between them they had at least 128 colonial-born children. A further 15 children arrived on the ship with their convict mothers. It is estimated there are over 100,00 people in Australia and New Zealand today who are descendants of the convict women from Friends.

"Women who went on to Van Diemen’s Land were Margaret Hughes, Martha Rowe, Margaret McDonald, Ann Osbourn, Mary Shadwell, Rachel Wright, Mary French, Mary Burgess, Mary Murphy and Sarah Wilson. " Elsbeth recounts.

“The colony was operating like an open prison at the time,” says Ms Hardie. “Women were assigned to work in the homes of settlers, administrators and officers in the NSW Corps. After a period of good behaviour they could go off and work on their own account, even before the end of their sentences.

“The women could also marry straight away. One woman, Elizabeth Brown, married just 10 days after the Friends arrived. Some of the women chose their partners well. Mary Norman – who had been convicted of passing forged banknotes - married another convict, Arthur Little, who later became a successful merchant and landowner. Mary moved with him into Rockwall, a listed building in Woolloomooloo that sold for just over $10 million last year.”

Ms Hardie says many of the women from the Friends disappeared into uneventful lives in New South Wales and Tasmania overtaken by respectability as they became wives and mothers in the colony. However, a handful of women remained in and out of trouble with the law. The child kidnapper Rachael Wright had over 20 convictions in Tasmania. Alcohol was often a factor in colonial crime and even led to the deaths of several of the women. London prostitute and thief Elizabeth Durant had a more savage death – the victim of a retribution killing by local Aborigines.

‘The Girl Who Stole Stockings’ focuses on the story of one of the youngest convicts on board Friends, and Elsbeth's predecessor, Susannah Noon, who was convicted at about 12 years of age in Essex and spent a year in goal before her long voyage here.

Prison Hulks on the River Thames, Woolwich, c.1856. © Greenwich Local History Library.

Set in the Macquarie convict era, this comprehensively researched non fiction account follows the lives of these women from a female perspective.

While researching Andrew Thompson, who left so much of his estate to Macquarie, we collected a lot of information regarding Hawkesbury River Whalers, both vessels and peoples, a series of stories we shall run at a later date. What surprised us in this research was how far such small vessels would go, even to New Zealand and back, or to the Bass Strait, well known for its testing weather patterns.

The Girl Who Stole Stockings shares records of this early European settlement of New Zealand and the shore-based whaling industry in the South Island, as this was Susannah Noon's ultimate destination.

“In telling Susannah’s story, this book has become an account of the women she travelled with to the colony, how they fared on the voyage, the unique convict regime of the Macquarie era, and the society that these women all helped to create,” says Ms Hardie. “For Susannah, that society extended to the shore-based whaling industry of New Zealand where she ended up living with a second husband though he had been already transported for bigamy.”

Her life in New Zealand made her a first-hand witness to the events that led to the fight at the Wairau between the land-grabbing New Zealand company and Te Rauparaha and his followers. This remains the only armed conflict between Maori and Pakeha in the South Island of New Zealand since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi.

Elsbeth's odyssey finding her relatives fascinated us of course. The extent of her work itself speaks volumes for its author, but did the experience of this research into something so personal as finding an ancestor bring something with it, as we so often find when following Pittwater history threads?; we took the opportunity to ask Elsbeth during her recent visit to our shores:

Did you see Susannah out the side of your eye while doing this work - or have a sense of your relative being 'present' with you? And if so, did she help you find 'things' or confirm 'things' where/when the trail disappeared?

Susannah was like a will o' the wisp; she was very hard to get a fix on. There was not enough information to form a complete impression of her. She lived before photography; there was no painting. I wondered continually what she looked and sounded like. I had a graphologist examine her signature and he told me that she was courteous, generous, a reasoned thinker, genuine, anxious, unsure of herself and that making a decision was not easy for her. That fitted with the few records left about her but I didn’t mention this in the book as graphology is not an exact science (it’s viewed a bit like astrology).

Susannah was like a will o' the wisp; she was very hard to get a fix on. There was not enough information to form a complete impression of her. She lived before photography; there was no painting. I wondered continually what she looked and sounded like. I had a graphologist examine her signature and he told me that she was courteous, generous, a reasoned thinker, genuine, anxious, unsure of herself and that making a decision was not easy for her. That fitted with the few records left about her but I didn’t mention this in the book as graphology is not an exact science (it’s viewed a bit like astrology).

Right: Elsbeth Hardie

I didn’t feel directed in any way by her, but I did “chance” upon a lot of information over the long period of research, particularly about other women who travelled with her on the Friends. I do know that she would have been horrified to think that I had revealed her life as a convict; something she would have striven to conceal in the latter part of her life.

During the first 100 years of European settlement in the New Zealand/Australian colonies there was a constant back and forth between the two, in fact, they were originally considered 'one station' - what was the New Zealand/er perspective on this?

The research for my book did not consider this extended period of history. Certainly when Susannah and her family arrived in New Zealand in the 1830s they looked to NSW to supply funding of the shore-based whaling stations and supplies, and a market for the oil and bone: the NZ whaling stations were satellites of the Australian whaling industry to a large extent. As you mention, many whalers lived between the two countries, returning to NSW after the end of each year’s whaling season.

After New Zealand became a formal colony of Britain at the end of 1840, it also started to export its oil and bone, as well as other raw materials, direct to Britain. Australia and New Zealand became economic competitors and also competitors for investment and settlers from Britain. The two countries continued to cooperate politically, to some extent, and there was an expectation in some quarters that NZ would federate with Australia in 1901 but this was not a popular move in New Zealand. By this time New Zealanders had established their own national identity and wanted to remain independent.

Whaling in Port Underwood - many locals travelled to New Zealand from the Hawkesbury to go whaling while it was still profitable - why live there, why not return to - did her husband have a position there that required being 'stationed'?

I think her husband Samuel saw a move to New Zealand as a chance to both acquire some capital running a whaling station and as the chance to cheaply obtain land. And, according to family accounts, he loved the area of the Marlborough Sounds which he considered a paradise. By the time he had served his sentence there were no longer free grants of land in NSW to former convicts. He did acquire land in Port Underwood. Personally, I think his history showed he was always looking for shortcuts to prosperity. It was a chance too to get away from officialdom. He could be his own man in New Zealand. And he could - eventually - leave his convict past behind him.

During your visit to Port Underwood did you find what you were looking for?

At the end of the book – in the Postscript - I describe running into the local farmer in Ocean Bay, Port Underwood, where they lived, who was able to point out various archaeological sites to me from the whaling days. I had visited the port several times before; this was the first time I looked so closely at how Susannah could have lived there. It was also very fortuitous that in the next bay south, an old and very small whaler’s cottage from the 1840s still survives there. So yes, I did get a sense of their lives there.

The final piece of the puzzle came only months before the book went off to the printers, when I found the long missing deed to the land Samuel acquired in Ocean Bay which confirmed they lived right in the middle of the bay, in the thick of the whaling activity.

____________________________________

With an extensive reference for each thread woven here The Girl Who Stole Stockings is a resource for all who are interested in this colonial period in the history of Australia and New Zealand and would make a valuable addition for all our schools and libraries.

Family Histories are a fascinating way of finding out more about where we came from, and in this instance, when Australia was first becoming a European colony and not so many people were here, a wonderful way of illustrating how entwined with the history of a place the footsteps of people may be and how this brings out what was happening and allows us insights into what people may have thought and how they reacted to the place they found themselves in.

Family Histories are a fascinating way of finding out more about where we came from, and in this instance, when Australia was first becoming a European colony and not so many people were here, a wonderful way of illustrating how entwined with the history of a place the footsteps of people may be and how this brings out what was happening and allows us insights into what people may have thought and how they reacted to the place they found themselves in.

Susannah was like a will o' the wisp; she was very hard to get a fix on. There was not enough information to form a complete impression of her. She lived before photography; there was no painting. I wondered continually what she looked and sounded like. I had a graphologist examine her signature and he told me that she was courteous, generous, a reasoned thinker, genuine, anxious, unsure of herself and that making a decision was not easy for her. That fitted with the few records left about her but I didn’t mention this in the book as graphology is not an exact science (it’s viewed a bit like astrology).

Susannah was like a will o' the wisp; she was very hard to get a fix on. There was not enough information to form a complete impression of her. She lived before photography; there was no painting. I wondered continually what she looked and sounded like. I had a graphologist examine her signature and he told me that she was courteous, generous, a reasoned thinker, genuine, anxious, unsure of herself and that making a decision was not easy for her. That fitted with the few records left about her but I didn’t mention this in the book as graphology is not an exact science (it’s viewed a bit like astrology).