May 12 - 18, 2013: Issue 110

THE KANGAROO

HUNT;

OR, A MORNING IN THE MOUNTAINS.

BY CHARLES

HARPUR.

AT length a belt of cedars tall

In a broad scoop,

[a] and undertwined

With brushwood of each gadding kind.

And with

the rankest vines,-is all

That interposing hides a scene

Where hunter

never hath bootless been.'

'Tis entered-and a sound up springs,

Of lashing

boughs and rushing wings!

In a desultorious throng,

Before, athwart,

above, along,

What birds their varied plumes display

Many and beautiful

are they!

The dove on burnished pinion strong

Hurries afar in sounding

flight,

And the yevowalas (b) unfold

Their pointed wings of

verdant gold

And fleetly flaming to the light

Above the doming cedars'

height,

Each one singly hits the view

Like a volant crystolite.

And the

rosella flashes through

The foliage orange, green, and blue

Mingling to

one checkered hue,

It seems a creature of rainbow birth,

Though somewhat

tarnished by the damp

Of its after life on earth ;

Or the scarlet satin

bird (c)

Hangeth like a golden lamp

Where the berried bird is

stirred :

While haply the king parrot, showing

Fall aloft his broad red

breast,

Like a vast blood-rich ruby glowing,

Near it boldly sits at

rest.

Or troops of rooks in loud Alarm

Mount the trees from arm to arm;

(d)

While crowds of nameless twittering things

With rich-ringed

glossy eyes, and necks

A]1 streaked and interstreaked, and wings

Spangled

with rows of spark-like specks,

And tails with broad bailed

blazonings.

And crimson backs, and bosoms bright

As the breast of a cloud

in a sunset sky,

Or glance afar in gleamy flight

O'er the leafy domes of

the cedars high,

Or lighten through the nearer shade,

Or sparkle aloft

like stars new-rayed,

Or stream in flocks, fright-disarrayed,

Like

shattered meteors by (e)

With these the noisy yellow-bill,

And

the ground parrakeet, (f) screaming shrill

About of some high

tussock near

It starts at once into the clear,

And seems while swiftly

shooting higher

Imped with plumes of subtle fire;

So vividly it hues the

light

As thus it blazes forth in flight;

And the whining quail that skims

the brush,

And the soaring pie, (g) and the dodging

thrush,

Precede the hunter as he pushes

Through clinging vines and

flaunting bushes,

Or sternly chides the loitering dog

That scents the wild

cat in the hollow log,

Or one that in pursuit would fly

As oft the

dooaralli (h) rushes bounding by.

(a) Or delve, as I had written in explanation, but looking into Johnson, I find the word delve defined as a ditch, a pitfal, a den, &c. I had previously understood it to mean a broad dip in the land, regularly bevelling' from side to side, as if scooped out by art; and I still fancy that this is the idea it would convey to the country English, and to all those who have ruralised somewhat more than great lexicographers are in the habit of doing.

Delves, then, or scoopes of the kind mentioned in the text, are often several miles long, by about a quarter of a mile wide, though in places much narrower. And even when they occur on tablelands, or on the backs of broad ridges, the soil in them is more than commonly fertile, it being chiefly an alluvion from the rising grounds on either tide. Hence they are always thickly timbered, and with trees of an extraordinary height, and are densely brushed besides with white cedars, kerrijongs, and a great variety of wild vines and wood-creepers. Out of this undermas.s of umbrage, the boles of the taller trees shoot up like crowds of pillar?, supporting faralott a second edition of dense foliage intertwined with runners of the kind described in a note to a subsequent portion of the Poem; and which mass of greenery, but for these its pillary supporters, were not unlike in distant appearance to a long and heapy stratum of darkly verdant cloud.

The multitude and variety of the feathered inhabitants of

localities such as these are easily accounted for, by the fact, that many of the

vines and creepers peculiar to them, are exceedingly prolific of seed-berries,

and are besides the murmevrous haunts' of innumerable insects.

[b)

Yeroncala is an aboriginal name of the blue mountain

parrot*-the most splendid, to my thinking, of all our parrots.

The rosella may be the more showy bird for a mouient, but even it will bear no

comparison with the blue-mountainer. Those persons who have only seen this bird

encaged, can have but a very imperfect notion of its native beauty. To arrive at

an adequate ideaof this, we must snare or shoot in the forest afull plumed cock

yerowala; and then the lustrous green of the whole back and wings, the

bright yellow of the breast, and the indescribable blue of the head, do indeed

compose for it an array most royal,

(c) This species of the satin-bird is somewhat rare. The whole

of the back, including the wings, is of a bright red or scarlet. In a commoner

sort the back and wings are of a glossy black; and in another 6pecies (if I

recollect aright) the same divisions of the plumage are of a vivid straw colour

our future ornithologists will look in vain for many kinds of birds which they

will find mentioned in the earlier colonial records. Being rare even at first,

these beautiful creatures often become exi met, and partly for the reason, that

not only species, but whole genera of birds are confined in Australia to

special, and, in some cases, very limited localities. I do not know whether this

is so much the case in other new countries, but any observer of such matters who

has travelled far into our interior, must be well aware that such is very

remarkably the fact here. I have myself seen two sorts of parrots in the

Kerrijong district thatI have never seen elsewhere, and particular birdsi n

particular localities that I have beheld out of them. Nay, I saw, when a boy, in

the wood about Windsor, no less than four peculiar kinds of birds, which I have

never since met with, although.

I have travelled extensively over the

country, and in almost every direction.

The unchecked increase of the large tree climbing guana in the waste portions of those districts in which the aboriginals have become extinct or nearly so, is a main cause of the extinction also of many kinds of our native birds. So numerous have these guanas become in the woods of our partly located districts, that in passing through these a mid-summer, we are apt to start one of them up every second or third tree ; Midhence, in such places only the nests of those birds that incubate early in the Spring and wholly exempt from the liability of being plundered by them. And if only for this reason, it is a pity that we Colonists do not esteem them as great a table delicacy as our sable forerunners-the former lords of the soil-undoubtedly did. For no doubt, when not too old, they are excellent eating,-something in taste between fish and fowl; and when baked, as the Blacks bake them,-that is covered up like a damper in hot ashes, they have an exceedingly rich and stomach-provoking savour.

(d) What is here called the rook is a gregarious bird having much the appearance of our black magpie, but with less white under the wings and none in the tail. When at rest or alight, it appears to be thoroughly black, the white places under the wings being only perceptible while they are spread in flight. On being started from the ground, where it feeds, it, flies heavily to one of the lower arms of the nearest tree, from which it then hops to a higher, and a higher, as described in the text, rounding the trunk at each stage of ascent, until it reaches the top,-when, deeming itself pretty safe it would seem, it quietly looks down upon the cause of its previous alarm.

(e) Those persons who are unacquainted with the surprising brilliancy of many of our native birds, may be inclined to question the descriptive veracity of the text. They may suspect that its illustrations are too glossy, as the phrase goes. ,Yet its most vivid pictures are but faint copies of the originals. How indeed could the splendour of the regent bird, for example, be adequately compassed in words, or fully granted even in idea ? That superb creature must be seen with the bodily eveind in the full plumed glow of its forest freedom ere we can have a believing conception of anything so gorgeous. Then the diamond -bird, with its sky blue wings be-droptd with miniature stars,-how flight a poet fully describe it, or a painter, even sufficiently paint it? And so of many others of our Australian birds - things of beauty' that Poetry can only catalogue at the best, and Palatine suggest.

(f) What is here called the ground parrakeet, from its always feeding upon the ground-on grass seed it is likely-is a small bird of exceeding beauty. To some extent it is even more splendid than the Yerowala. Its prevailing colour is green, variagated with bright yellow blazes in the wings and tail. While at rest, however, it is a small queen bird of no very brilliant appearance; but no sooner are its wings and tail dispread in flight, than it becomes vivid as fire. There are, however, several varieties of this kind of parrot, all somewhat different coloured ; and one of these, though less splendid than the one above described, is yet more intensely beautiful upon a close inspection.

(g.) As I have before noted, there are at least two kinds of so called magpies - the ' black and white,' or Australian magpie proper, and the' black' or migratory magpie, a bird less spotted. Both of these birds are remarkable for the beauty of their eye, though the former is not in this respect at all comparable with the latter; the eyes of which are so strikingly fine, that my son Washington, when about four years old, was wont to refer to it through this characteristic-calling it' the big black bird with the new eyes.'

(h) Dovralli is the name the Blacks of some parts of

the interior give to the animal commonly called the Kangaroo-rat.

(To be

continued.)

THE KANGAROO HUNT; OR, A MORNING IN THE MOUNTAINS. (1860, October

6). The Australian Home Companion and Band of Hope Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1859 -

1861), p. 13. Retrieved May 11, 2013, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article72484897

* Blue mountain parrot is what we call now rainbow lorrikeet

Judith Wright, in Authority and Influence: Australian Literary Criticism 1950-2000, states, "Charles Harpur seems to have chosen his calling early. His life from his youth onward was to be remarkable for the tenacity and dedication with which he clung to the almost impossible task of laying the foundation for an Australian poetry, under conditions that would have discouraged most writers."

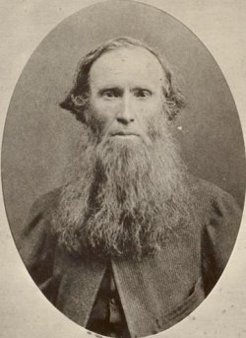

Charles Harpur

(1813-1868) Determined to be labelled Australia’s ‘first poet’ Charles

Harpur pursued a literary career and was known as a critic through publication

of many pieces in colonial Australia. Born on 23 January 1813 at Windsor on the

Hawkesbury river to Joseph Harpur and Sarah, née Chidley, both convict

transportees who arrived in 1800 and 1806 respectively, Charles Harpur seemed

determined to become a respected amateur naturalist (a then popular fashion) and

was aided in this pursuit as is father became a schoolmaster and taught him or

gave him access to English poets.

Charles Harpur

(1813-1868) Determined to be labelled Australia’s ‘first poet’ Charles

Harpur pursued a literary career and was known as a critic through publication

of many pieces in colonial Australia. Born on 23 January 1813 at Windsor on the

Hawkesbury river to Joseph Harpur and Sarah, née Chidley, both convict

transportees who arrived in 1800 and 1806 respectively, Charles Harpur seemed

determined to become a respected amateur naturalist (a then popular fashion) and

was aided in this pursuit as is father became a schoolmaster and taught him or

gave him access to English poets.

The patronage of Governor Lachlan Macquarie, John Macarthur, Samuel Marsden and theThomas Hassall family benefited Joseph Harpur materially and in social status, so that a prosperous home and its leisure, access to private libraries, and his father's encouragement enabled Charles to acquire an education beyond what would otherwise have been his lot. During four decades Harpur's contributions to the periodical press were undoubtedly more numerous than those of any other Australian writer. These were either literary: verse and criticism; or political: republican, against transportation, for self-government and adult franchise, for opening up of the land. His writings were given these directions very early, for even in the 1820s other Australian youths, Currency Lads, had literary as well as political ambitions for their country. Among these were Charles Tompson, Joseph Harpur, John Walker Fulton and Horatio Wills. William Charles Wentworth was their hero. Horatio Wills's paper, the Currency Lad, published Harpur's early verse.

Harpur associated with, and his work was admired by, literary men of the day: Duncan, Nicol Stenhouse, Henry Halloran, Henry Parkes, W. G. Pennington, James Norton, Dr John Le Gay Brereton, D. H. Deniehy and Henry Kendall. The last two were ardent admirers, though there were less panegyrical critics. After a period of belittlement some modern critics have come to claim a higher place in our estimation for a poet who, in the words of Henry Mackenzie Green, was 'the first to break through the tough crust of a crude materialistic age and compel the attention of at least a few to the fact of poetry's emergence in this new country' and who, as Judith Wright sees him, 'remains the most significant, because the most many-sided and thoughtful, of our nineteenth-century poets, until Brennan began writing at the end of the century'.

Besides being a poet, Harpur saw his role as that of a patriot, not a chauvinist, whose task it was to help make his country worthy of esteem, and to lead and to warn and to strike at wickedness in high places and in low, and like some Hebrew prophet to thunder judgment. While, he said, nothing could shake his belief in God, he rejected all Christian sects, Unitarianism coming nearest to his conception of religion. But his standards were high, his standards for individual righteousness and for collective and governmental morality. He could not keep silent, whether it were friend or foe who offended. There was much to thunder about in mid-century Sydney and much to sadden a sensitive poet with the outlook of a seer and prophet.1.

1. J. Normington-Rawling, 'Harpur, Charles (1813–1868)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/harpur-charles-2158/text2759

Charles Harpur (1813-1868), by unknown photographer,

1860s

National Library of Australia, nla.pic-an23436164