November 2 - 8, 2014: Issue 187

True Light and Shade: An Aboriginal Perspective of Joseph Lycett's Art by Professor John Maynard

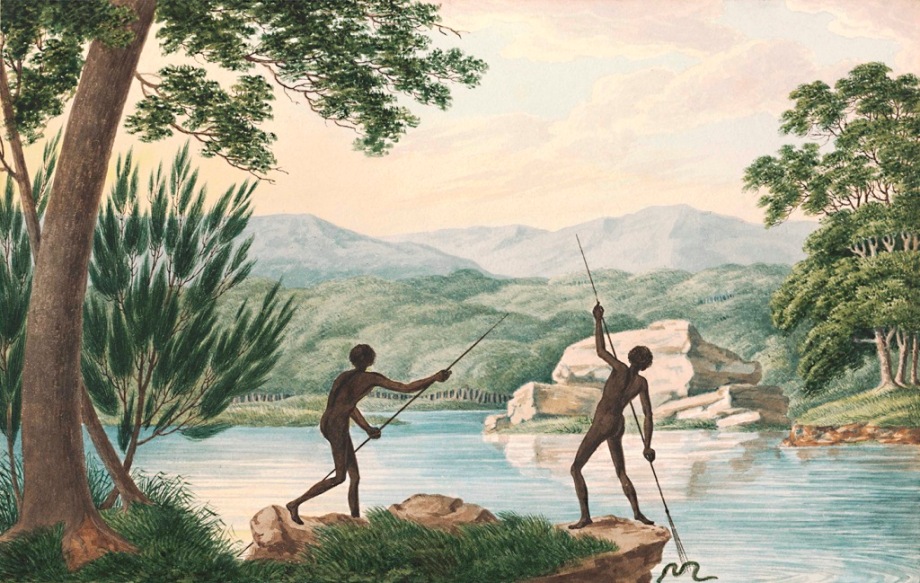

Aborigines Spearing Fish, Others Diving for Crayfish, a Party Seated beside a Fire Cooking Fish. P113-119.

True Light and Shade: An Aboriginal Perspective of Joseph Lycett's Art by Professor John Maynard

For those who love history and art this new book from the National Library of Australia with wonderful commentary by Professor John Maynard, Professorial Chair and Head of the Wollotuka School of Aboriginal Studies at the University of Newcastle and a Worimi man from the Newcastle - Port Stephens region, offers rare insights into the works of one of our premier convict artists and Newcastle as it was at the time of European settlement. Featuring 20 images from this renowned artist and a focus on the place where Bungaree originally hailed from, this should be of interest to all peoples of the Broken Bay and Pittwater regions.

The title quote ‘true light and shade’ comes from Lycett’s words: ‘I consider a complete drawing to be an accurate delineation of anything with its true light and shade.’

What was judged as the hell hole of New South Wales - Coal River, and present day Newcastle, the truer reflection of this landscape and its peoples can be seen in its Aboriginal name Mulubinba (the place of sea ferns).

During this past week we were able to speak to Professor Maynard about this book and chose a few of the 20 as our focus:

These pictures show a garden landscape of Mulubinbah (place of sea ferns) 'Newcastle' and land of plenty reiterate a seasonal abundance. Was life idyllic for the original custodians of this land or were there challenges and if so, what caused these ?

Clearly, as I state throughout True, Light and Shade, the Newcastle area including Lake Macquarie, mountains, Hunter Valley and Port Stephens was a ‘virtual paradise of plenty’ for Aboriginal groups. The abundance of rich and varied resources could support large populations of Aboriginal people who did not have to travel vast distances to acquire food. The sheer size and variety of marine delicacies readily available were commented upon by early British accounts including Lieutenant William Sacheverall Coke ‘we catch here eight or nine large fish called schnapper in an hour, numbers of salmon, mullet and we are obliged to kill four or five sharks there are so many… the blacks swam to the seabed returning with lobsters four times larger than those in England’.

Lieutenant James Grant, in Command of the Lady Nelson visiting the Hunter River in 1801, observed ‘the shore was covered to a great depth with oyster shells’. These massive middens were noted to have stretched from the present day Newcastle Harbor some eleven kilometres along the Hunter River. There was, as Lycett shows, plenty of time for leisure, sport and a rich ceremonial life.

That is not to say that the Aboriginal groups did not have to cope with Australia’s at times unpredictable climate and environment. The local groups witnessed great change going back some 10 to 20 thousand years of the last Ice Age. In the aftermath, rising sea levels submerged a third of what we know today as Australia. The coast was probably some 200 kilometres to the east.

Newcastle and the Hunter, besides earthquakes, has witnessed catastrophic flooding as seen with the 1955 Maitland flood. There are accounts of Aboriginal men pointing to marks high in the treetops and explaining to white settlers, with a warning, that this was the high water mark in this vicinity. The advice, in most instances, was laughed at and ignored. Aboriginal people themselves had built up thousands of years of knowledge on these dramatic events and heeded their warnings.

I believe catastrophic bushfires were not as prevalent prior to 1788. The continual burning off by Aboriginal groups had transformed the Australian landscape into what early settlers described as parklands. Bill Gammage’s recent award winning book The Biggest Estate on Earth – How Aborigines Made Australia - details these Indigenous influences upon the landscape.

The bush we know today is very different to that encountered by settlers in 1788. The massive cedar forests that came to the very shores of the Hunter River in Newcastle and were prevalent across the state were decimated. The introduced European weeds, scrubs, plants and trees spread rapidly and were in most instances highly combustible. The land without constant burning and these introduced species (pests) transformed a highly controlled bush environment into one of catastrophic unpredictability. No greater example need be put forward than the 2003 Canberra bush fires culminating in several deaths, hundreds injured and over 250 million dollars in damage.

Aboriginal use, knowledge and respect for their environment was all about ensuring that the land was cared for and protected and passed on to the following generations.

The ceremonial aspects of Aboriginal life appear time and again in each picture of Lycett's - why would he have been given access to these and permission to depict them?

The detail captured by Joseph Lycett in his coverage of Aboriginal ceremonial life can only have been gained by someone who had established great trust and respect within the local Aboriginal groups. Clearly Lycett had a great interest in Aboriginal life and he operated in a culturally appropriate and sensitive manner. In saying that, Aboriginal people would not have allowed the presence of someone at secret/sacred initiation ceremonies. The events that Lycett captured are open access events with no barriers to attendance (as an example young children are present pg. 105). The event is more performance-based – a corroboree with lots of dancing and singing, a night of great entertainment. Everything was not always a secret sacred ceremony, Aboriginal people could obviously enjoy a night out.

Aborigines Resting by a Camp Fire near the Mouth of the Hunter River, Newcastle: This beautiful picture shows Nobby's Island and you explain in the text 120 feet (37 metres) was taken off the top of this island to be used in the construction of a break-wall to connect the island with the mainland. How many physical changes to the landscape can you chart through these pictures and why couldn't the 'dreamtime' forming of the landscape and its sacred value, just as it is, be communicated to Europeans to stop such changes?

It was a collision of seismic proportions of two completely differing cultures. One culture that respected the land, environment, flora and fauna in religious terms of veneration and one that saw the land and all within as a commodity to be taken, conquered and controlled. The land could then be bought and sold and plundered for every possible gain economically with no consideration of the future. When one looks at the Lycett images and visits those sites today you are immediately struck by the incredible change in just a few hundred years. Those locations had been nurtured for thousands of years basically without a stone being disturbed by human hands

The Giant Kangaroo of Whibay-gamba tells of landscape, traditions for law, and also of the landscape being prone to earthquakes through this cultural knowledge. Have you found much evidence of settlers being aware of seeing the landscape and its forms as a divinity?

I can’t say I have found any early evidence of settlers viewing the landscape in religious terms of understanding. As I have said above, land and its resources in the most brutal fashion are measured as a commodity to be exploited and make profit from with no consequence of the end result. Still today we are witnessing this stampede for profit at all cost with little thought for future generations and their very survival. It is important to also note the impact of religion. Despite the missionary Lancelot Threlkeld being a supporter, Aboriginal people were nevertheless categorised as heathen savages who needed saving.

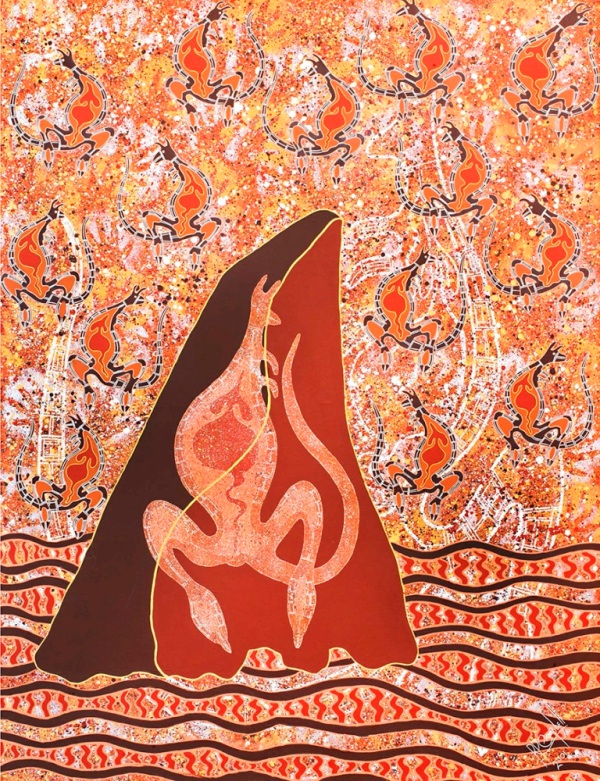

Richard P. Campbell, The Giant Kangaroo of Whibay-gamba (p. 103)

Two Aborigines Spearing Eels; throughout this book you have shared insights, not only the seasonal produce that came in seasonal tides but also the cultural aspects of who ate what within a group - could you share with us an insight into this?

Aboriginal people advanced through varying steps of the initiation process. In some ways it was like progressing through a Diploma, Degree, Honours, Masters and PhD at university. One was demonstrating that they had successfully passed the requirements of each stage and step of education and knowledge. The steps recognized progress with the opening up of intricate stages of knowledge and wisdom and various food items that were only available to those at the differing levels of knowledge. This also established a form of pension or aged care scheme where those who had attained the position as Aboriginal people of high degree had access to all forms of food whilst the young fit and agile were restricted to what they could consume. The end result of such rules and regulations ‘are to prevent the young men from possessing themselves, by their superior strength and agility, of all the more desirable articles of food’.

Which is your favourite among the Lycett pictures and why?

I truly have so many favourites of Lycett’s work but if I had to choose one I guess it would be ‘Aborigines Resting by a Camp Fire, near the Mouth of the Hunter River, Newcastle, NSW (P113). As someone who was born in Newcastle it grounds an Aboriginal presence in the here and now of the city with prominent land marks clearly visible. The image captures beautifully the serenity and closely connected communal feeling of traditional Aboriginal life. Mulubinba (the place of sea ferns) unlike the European description as the ‘hell-hole’ Coal River was a place of incredible beauty. The British imposed their strict laws, regulations and firm control. Mulubinba as a penal settlement for convict confinement, complete with the brutal use of the lash and destruction of the environment was an attempt to transform, erase and disguise the landscapes beauty.

Aborigines Resting by a Camp Fire near the Mouth of the Hunter River, Newcastle.

True Light and Shade: An Aboriginal Perspective of Joseph Lycett's Art by Professor John Maynard.

Publisher: National Library of Australia. Edition: 1st Edition. Pages: 172. Publication Date: 01 November 2014. Price $49.99

Publisher: National Library of Australia. Edition: 1st Edition. Pages: 172. Publication Date: 01 November 2014. Price $49.99

True Light and Shade is filled with beautiful images by convict artist Joseph Lycett that powerfully capture in intimate detail Aboriginal life, a rare record of Aboriginal people within the vicinity of Newcastle and how they adapted to European settlement before cultural destruction impacted on these groups.

John Maynard writes an engaging short biography of Lycett and his life in Australia and follows this with a detailed commentary on each of the 20 images in the album. Each image is reproduced in full on a double page spread and then, on the spreads following, details have been enlarged to accompany John's text as he takes us through exactly what is happening in every picture: ceremony, hunting and fishing, carrying food (carving up whalemeat), land management and burning, interactions with Europeans, family life, dances, funeral rituals, and punishment. When you return again to examine the full image, you see it in a completely different light. John also includes written records from the time that corroborate Lycett's views.

Some dreamtime stories connected with the areas Lycett depicted are also included, with accompanying Indigenous art. One story explains the earthquakes in the area (kangaroo jumping up and down).

The title quote ‘true light and shade’ comes from Lycett’s words: ‘I consider a complete drawing to be an accurate delineation of anything with its true light and shade.’

As a Worimi man from the Newcastle/Port Stephens region, John Maynard brings his own knowledge and insight to his exploration of the drawings, and to the fascinating character of Lycett himself. John is currently a Director at the Wollotuka Institute of Aboriginal Studies at the University of Newcastle and Chair of Indigenous History. He has held several major positions, including as Deputy Chairperson of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies and Deputy Chair Humanities, National Indigenous Research and Knowledges Network.