inbox and environment news: Issue 551

August 21 - 27, 2022: Issue 551

Masked Lapwing Plover Chicks Were In Danger: Now They're Dead

Local councils responsibilities as defined under the Local Government Act 1993 directs councils to properly manage, develop, protect, restore, enhance and conserve the local environment for which it’s responsible, in a manner that’s consistent with and promotes the principles of Ecologically Sustainable Development.

That's why it was so surprising to see the local council recommending formalising illegal bike tracks at Ingleside and North Narrabeen, where wildlife was once safe and could live in peace, and where at least one wallaby has already been run over by a biker. Visit: Council's Open Space and Outdoor Recreation and Action Plan Open For Feedback: Supports Formalising Illegal Bike Tracks In Bush Reserves and Public Parks feedback closed August 14.

Under the Local Government Act 1993 :

36E Core objectives for management of community land categorised as a natural area

The core objectives for management of community land categorised as a natural area are—

(a) to conserve biodiversity and maintain ecosystem function in respect of the land, or the feature or habitat in respect of which the land is categorised as a natural area, and

(b) to maintain the land, or that feature or habitat, in its natural state and setting, and

(c) to provide for the restoration and regeneration of the land, and

(d) to provide for community use of and access to the land in such a manner as will minimise and mitigate any disturbance caused by human intrusion, and

(e) to assist in and facilitate the implementation of any provisions restricting the use and management of the land that are set out in a recovery plan or threat abatement plan prepared under the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 or the Fisheries Management Act 1994.

36J Core objectives for management of community land categorised as bushland

The core objectives for management of community land categorised as bushland are—

(a) to ensure the ongoing ecological viability of the land by protecting the ecological biodiversity and habitat values of the land, the flora and fauna (including invertebrates, fungi and micro-organisms) of the land and other ecological values of the land, and

(b) to protect the aesthetic, heritage, recreational, educational and scientific values of the land, and

(c) to promote the management of the land in a manner that protects and enhances the values and quality of the land and facilitates public enjoyment of the land, and to implement measures directed to minimising or mitigating any disturbance caused by human intrusion, and

(d) to restore degraded bushland, and

(e) to protect existing landforms such as natural drainage lines, watercourses and foreshores, and

(f) to retain bushland in parcels of a size and configuration that will enable the existing plant and animal communities to survive in the long term, and

(g) to protect bushland as a natural stabiliser of the soil surface.

Councils also have a range of functions, powers and responsibilities that can influence NRM on public and private land. This includes strategic planning and development control, managing public land, and regulating private activities. Natural Resource Management (NRM) activities include biosecurity, stormwater, biodiversity, roadside environmental management, water quality, as well as restoration and rehabilitation of habitat and support to local bush care and land care activities. They do not as yet specify any required response to wildlife in peril in these LGA's.

However, no council in Sydney states it is or will be responsible for the wildlife living within these LGAs. No legislation compels them to do so.

All councils refer you on to wildlife organisations that exist solely because of volunteers who also pick up all the costs for saving local wildlife, as well as donating hundreds of hours each month to look after animals that come into care.

Council's Bushland and Biodiversity Policy Statement, published February 2021, outlines their own current commitments.

Public Meeting On Northern Beaches Aboriginal Lands Approval By State Government

Leopard Seal Visitor

.jpg?timestamp=1660590847423)

Echidna 'Love Train' Season Commences

Dogs Off-Leash On Beaches Open For Feedback

- Calls For Council To Address Dogs Offleash Everywhere After Two Serious Dog Attacks On Local Beaches In Same Week - owner has still not come forward or been identified as of Saturday August 6, 2022

- Sydney Dog Attack Victim Awarded $225, 000: July 2022

- Council Push For Dogs Off Leash On Family Beaches Among Wildlife Habitat

White faced heron landing at north Palm Beach, March 7th, 2022 during storm event. All native birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals (except the dingo) are protected in New South Wales by the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (BC Act).

Magpie Breeding Season: Avoid The Swoop!

- Try to avoid the area. Do not go back after being swooped. Australian magpies are very intelligent and have a great memory. They will target the same people if you persist on entering their nesting area.

- Be aware of where the bird is. Most will usually swoop from behind. They are much less likely to target you if they think they are being watched. Try drawing eyes on the back of a helmet or hat. You can also hold a long stick in the air to deter swooping.

- Keep calm and do not panic. Walk away quickly but do not run. Running seems to make birds swoop more. Be careful to keep a look out for swooping birds and if you are really concerned, place your folded arms above your head to protect your head and eyes.

- If you are on your bicycle or horse, dismount. Bicycles can irritate the birds and the major cause of accidents following an encounter with a swooping bird, is falling from a bicycle. Calmly walk your bike/horse out of the nesting territory.

- Never harass or provoke nesting birds. A harassed bird will distrust you and as they have a great memory this will ultimately make you a bigger target in future. Do not throw anything at a bird or nest, and never climb a tree and try to remove eggs or chicks.

- Teach children what to do. It is important that children understand and respect native birds. Educating them about the birds and what they can do to avoid being swooped will help them keep calm if they are targeted. Its important children learn to protect their face.

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

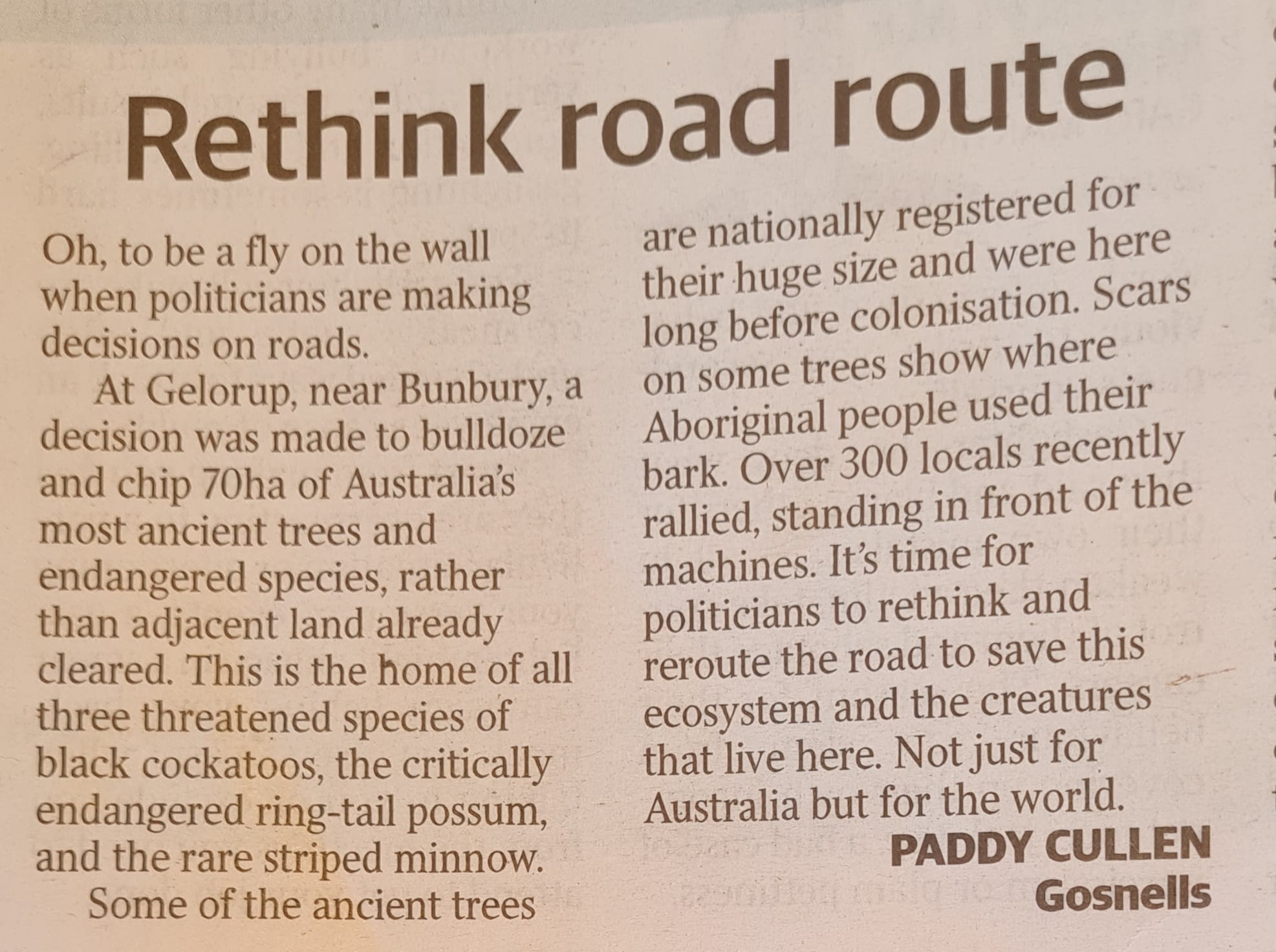

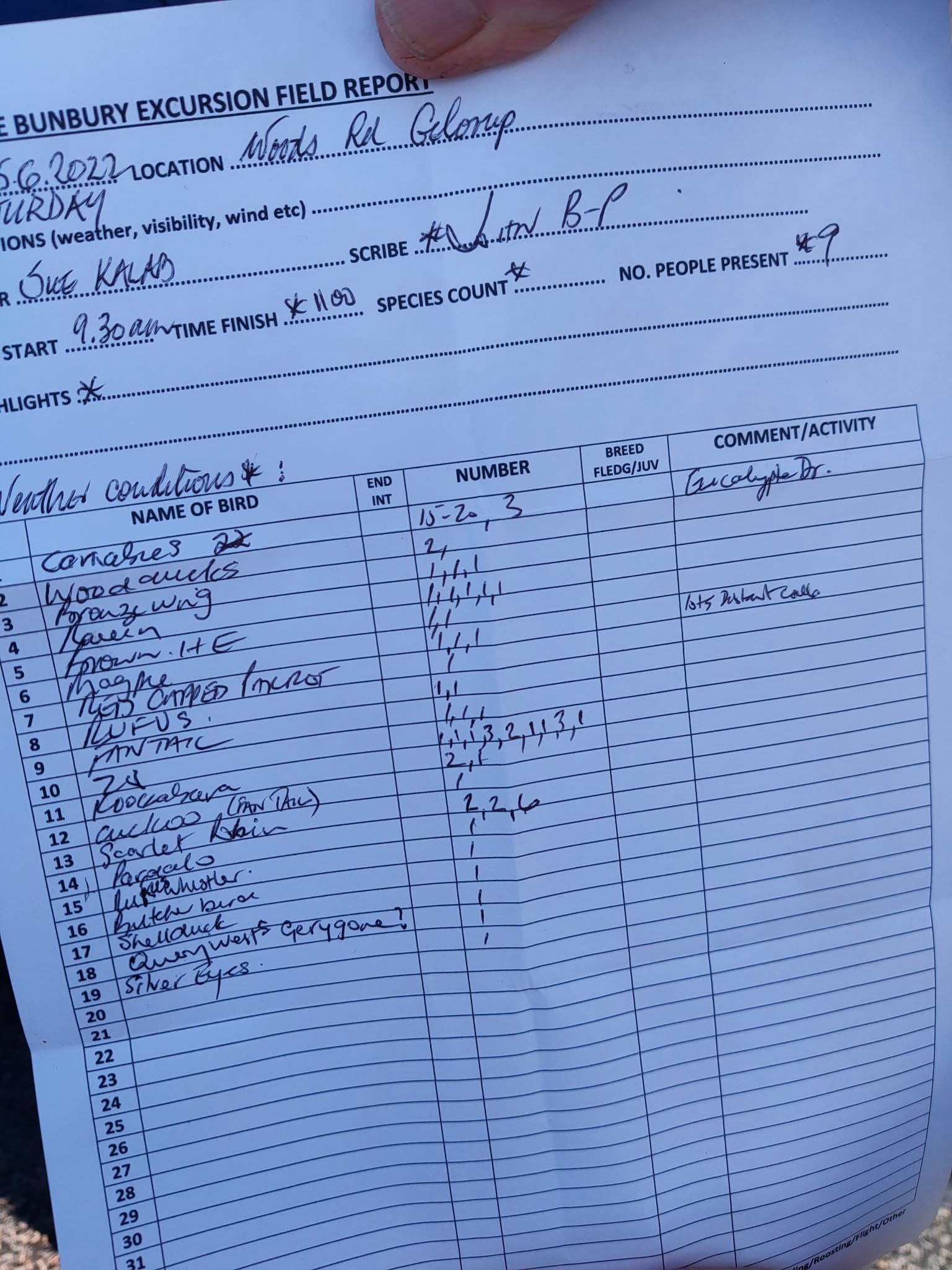

Plibersek Wins Federal Court Backing To Destroy Habitat Of Critically-Endangered Species In Gelorup Corridor: Roads Plan Ignores Already Cleared Land Alongside

Formal Consultation On Safeguard Mechanism Reform Opens

- setting baselines for existing and new facilities;

- setting indicative rates for baseline decline;

- lowering costs through crediting over performance and the use of offsets;

- identifying options for tailored treatment for emissions-intensive, trade-exposed businesses; and

- taking account of available and emerging technologies.

Dungowan Dam Evauluation 'Costs Far Outweigh Any Benefit'

'While the New Dungowan Dam and Pipeline will have community benefit and increase resilience, it is a significant infrastructure intervention with costs that far outweigh the benefits that will be delivered. Based on our assessment, the Increased Urban Reserve option (Chaffey Dam), which is also considered in the business case, appears to be a feasible, lower cost solution that addresses the problem and warrants further detailed consideration.'

Infrastructure Australia has finalised its independent assessment of the business case for the New Dungowan Dam and Pipeline in accordance with the Infrastructure Australia Assessment Framework. The proposal has not been added to the Infrastructure Priority List at this time.The New Dungowan Dam and Pipeline aims to increase town water supply for Tamworth and maintain water reliability for agricultural production in the Peel Valley. The proposal was developed in response to long periods of drought and water restrictions. At a time in 2019, Tamworth was 12 months away from running out of water from its primary water source, the Chaffey Dam.The project has a capital cost of more than $1 billion and a benefit cost-ratio of just 0.09. Although it offers sustainability and resilience benefits, our assessment found that similar community benefits could be achieved through a combination of lower cost build and non-build options.This includes increasing the amount of water from Chaffey Dam that is available for urban use, along with policy changes such as demand management and water use efficiency measures.We would welcome a revised business case for an investment solution that better aligns to the identified problems and opportunities for providing increased water security to the Tamworth region.Infrastructure Australia Chair Col Murray declared a conflict of interest in relation to this project and was not present during any discussion or decision-making relating to the business case assessment, in line with Infrastructure Australia’s Conflict of Interest Policy.

''The option has been recommended on the basis that “the other options do not develop new capacity and therefore focus on shifting the burden of the existing level of service, which is expected to decline, between different stakeholders either within the Peel Valley or Namoi region.” This is inappropriate, as the problem that has been identified is the need to address Tamworth’s water security risk (i.e. access to water), rather than increasing the storage capacity in the region. Economic analysis of the three options presented in the business case demonstrates that the water security risk is more efficiently addressed by options that do not involve the development of new capacity. The Increased Urban Reserve option returns a significantly better BCR and NPV result than the other shortlisted options, outperforming the New Dungowan and Pipeline option in terms of the quantified benefit from improved water security ($3.85 million compared to $3.43 million).The recommendation of the preferred option is based primarily on the outcomes of a Strategic Merit Test, which has not been well explained. Specifically, the Increased Urban Reserve option scored poorly in relation to investment decision readiness and stakeholder acceptance. This is not supported by the results of the cost-benefit analysis or other information in the business case. In relation to the risk associated with stakeholder acceptance, the cost-benefit analysis includes quantification of the disbenefit attributable to the reduced reliability of supply for irrigators in the Peel Valley. This disbenefit is quantified at only $660,000 in PV terms under the Increased Urban Reserve option. This indicates the adverse impact on irrigators is highly likely to be mitigable at low cost.Compensation to non-urban users was not considered in the Increased Urban Reserve option. In addition, the poor performance of this option in terms of investment readiness gives insufficient consideration to the lack of infrastructure required to implement it, whereas the New Dungowan Dam and Pipeline option would not be completed until 2029.Further assessment, including hydrological, economic, and ecological analysis, will provide greater understanding of the feasibility of the Increased Urban Reserve option. Hence, having regard to the results of the cost-benefit analysis and justification of the assessment of the shortlisted options in the Strategic Merit Test, the identification of the New Dungowan Dam and Pipeline option as the preferred option appears inappropriate. The Increased Urban Reserve option achieves greater benefits at significantly lower economic cost, with limited deliverability risk.

- Local water utility and Domestic and Stock water access licence holders received an allocation of 70% of entitlement.

- High security water access licence holders in the Peel Regulated River water source and its sub categories received an allocation of 50% of entitlement.

- General security water access licence holders received an allocation of 0% of entitlement.

- All local water utility and Domestic and Stock water access licence holders in the Peel Unregulated River, Peel Alluvium and Peel Fractured Rock water sources received an allocation of 100% of entitlement.

- In the Peel Alluvium water source, aquifer access licence holders received an allocation of 100% of entitlement, while aquifer (general security) access licence holders received an allocation of 51% of entitlement.

- Peel Unregulated River water access licence holders received an allocation of 100% of entitlement.

- Aquifer access licence holders in the Peel Fractured Rock water source received an allocation of 100% of entitlement.

Water For Brewarinna Update (February 2020 Community News Page)

#YaamaNgunnaBaakaBusy couple of days delivering 15L water bottles throughout the Brewarrina Community especially to the Elders and those on dialysis.Hopefully this will go some way to helping the people before clean drinking water becomes available again. Those of you with water bottles please keep for refills, we don’t want to have plastic waste #SavingOurWater #NoPlasticWasteSpecial thanks to-Neil and the Northern Beaches mob- and Robert and staff from IGA in Bourke for their support.

- Yamma Ngunna Baaka - From The Northern Beaches To Bre: Our Sister City Shares Its Water Woes - October 2019

- Water Activists United Call At Newport Meeting For Greater Flows In The Baaka – The Murray-Darling Basin - November 2019

- Christmas Appeal Launched For Aboriginal Kids In Sister City Brewarrina - November 2019

- Narrabeen Bridge Protest Demands Water For Rivers - March 2020

Wilcannia Weir Project Delivers Water And Jobs

Miner MMG Remove Machines From Tasmania’s Forests Under Environmentalists Supervision

Climate Driver Update - Wet Outlook Continues With An Increased Chance Of La Nina Developing This Spring

Governments And The Healthcare Sector Must Lead On Climate Change AMA And DEA Say

- A net zero Australian healthcare system by 2040 with majority of emission cuts by 2030.

- The development of a national climate change and health strategy to facilitate planning for climate health impacts, which the federal government has committed to.

- Establishing a National Sustainable Healthcare Unit to support environmentally sustainable practice in healthcare and reduce the sector’s own emissions.

- Education of current and future doctors to:

- be well equipped to care for patients and populations impacted by the adverse health effects of climate change, and

- provide sustainable health care to support sector-wide emissions reduction.

- Collaboration on climate change mitigation strategies with populations most at risk of climate-related adverse health impacts, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Applications Now Open For 2022 Gone Fishing Day Grants

It’s Raining PFAS: Even In Antarctica And On The Tibetan Plateau Rainwater Is Unsafe To Drink

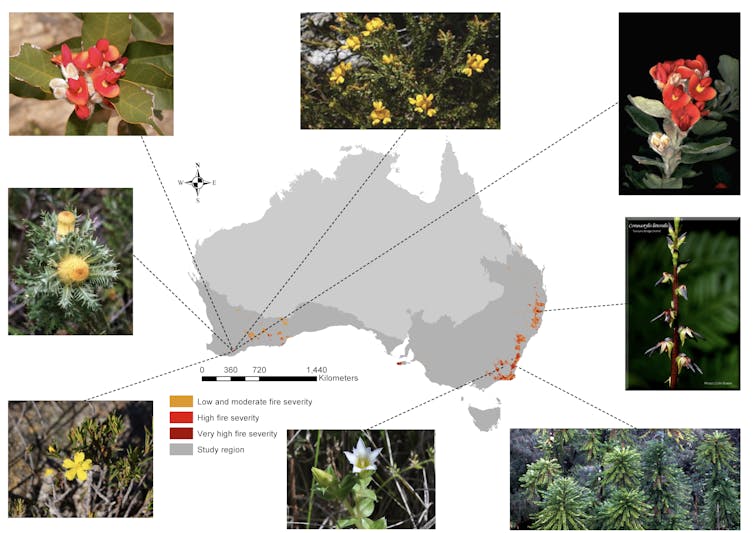

Wildlife recovery spending after Australia’s last megafires was 13 times less than the $2.7 billion needed

Few could forget the devastating megafires that raged across southeast and western Australia during 2019-20. As well as killing people and destroying homes and towns, the fires killed wildlife and burnt up to 96,000km² of animal habitat – an area bigger than Hungary.

Under climate change, megafires will become increasingly common. This is likely to leave many species needing help at the same time, over vast areas. So our new research, released today, devised a way for conservation scientists and others to determine which actions, and where, will best help wildlife recover.

We also put a price tag on these measures. We found about A$2.7 billion should have been spent across Australia in the year after the megafires to mitigate all threats to 290 severely affected threatened animal and plant species. This is almost 13 times the funding dedicated by the former federal Coalition government.

The paltry spending means many species severely harmed by the megafires were left in desperate trouble, potentially pushing some closer to extinction.

The First Year Is Crucial

Many plant and animal species are especially vulnerable in the first year after a fire.

Fires can allow invasive weeds to invade and dominate burnt areas. This can hinder the ecosystem’s recovery, including making it more fire-prone.

Many native animals such as Kangaroo Island dunnart and long-footed potoroo rely on vegetation cover to avoid invasive predators such as feral cats and foxes. When fire removes this vegetation, native animals have nowhere to hide.

After a fire, any patches of unburnt vegetation are crucial for animals that survived. But invasive herbivores such as horses, deer, and pigs can graze on these food sources, leaving little for native wildlife.

For these reasons, the first year after a fire is usually the most important time to implement actions to help vulnerable species recover. Such actions can include:

- protecting habitat

- managing invasive plants and animals

- stopping native forest degradation associated with logging

- limiting damage from recreation activities

- managing disease.

But in the immediate aftermath of a fire, how do conservation scientists and others decide which species to help, and how? Which locations should they prioritise? And how does all this interact with other threats to wildlife such as land clearing and feral predators?

To date, decision-makers around the world have largely used a method known as the “site richness” approach to prioritise conservation actions. This approach concentrates actions in locations where the greatest number of species can be recovered.

But this approach can mean some high-risk species may not get the help they need, while other less critical species receive disproportionately high assistance.

For example, research from China has showed relying entirely on this method meant species of woody plants found only across a small range – and therefore potentially vulnerable – missed out on conservation actions.

Our New Approach

Our new research devised and assessed an alternative method. Known as the “complementarity” approach, it ensures conservation actions occur across the habitats of all threatened species. It involves combining data about:

- the distribution of species and threats

- fire extent and intensity

- a species’ risk of severe, irreversible decline after a fire.

From that, decisions can be made about which of the 22 conservation actions should be carried out first, and where. It prioritises locations where threats affect multiple species – making it more cost-effective to deal with them – and where actions at one site can be easily extended to nearby areas.

We then applied our framework to the 2019–2020 bushfires to identify the most at-risk species, the actions needed to save them, the best locations for these actions, and the costs.

Our approach identified 290 threatened species needing immediate conservation attention. They spanned mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs, insects, and plants.

Each species required, on average, three conservation actions to mitigate threats. The top three were habitat protection (all species), fire suppression (57% of species) and invasive plant management (36% of species).

We then prioritised cost-effective actions after the fires, using our approach. We found actions should take place in 179 geographic areas, including the Snowy Mountains in New South Wales and Gippsland in Victoria.

Actions in these regions recovered the highest number of at-risk species – such as koalas, greater gliders and regent honeyeaters – for the least cost.

We found A$2.7 billion would be needed to mitigate all threats to 290 species in the year after the megafires.

But the previous federal government committed just $200 million to post-fire recovery actions. Some $50 million of this was delivered relatively quickly. But the remainder was to be delivered over two years from July 2020 – beyond the timeframe in which many species required urgent help.

Heeding The Lessons

Our research shows the potential gains from alternative approaches to conservation after devastating fires. It also underscores the need for adequate government funding, delivered quickly, to help species most in need.

It’s worth remembering the loss of habitat from bushfires often compounds decades of land clearing. As Australia faces an ever-worsening bushfire risk, we urge Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek to prevent further loss of threatened species habitat.

Michelle Ward, Postdoctoral research fellow, The University of Queensland; Ayesha Tulloch, ARC Future Fellow, Queensland University of Technology, and James Watson, Professor, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No, not again! A third straight La Niña is likely – here’s how you and your family can prepare

Mel Taylor, Macquarie University and Katharine Haynes, University of WollongongHearts sank along the Australian east coast this week when the Bureau of Meteorology announced a third consecutive La Niña was likely this year. La Niña weather events typically deliver above-average rainfall in spring and summer.

But the last two La Niñas mean our catchments are already full. Dams are at capacity, soils are saturated and rivers are high. In some cases, there’s nowhere for the rains to go except over land.

Over the past 18 months, many communities have been hit by floods – some more than once. For these residents, the prospect of a third La Niña will be extremely concerning. And some people who’ve never experienced floods may now be at risk.

Our current research project is examining the experiences of flood-hit communities in New South Wales and Queensland – and our interviews have already yielded useful insights. So let’s take a look at what we should be thinking about now as another wet summer looms.

Water Isn’t Always Fun

Floods are among the deadliest natural hazards in Australia. Yet in Australian culture, water often equates to fun. From a young age we’re taught to swim, enjoy and “master” the dangers that water poses.

So during floods we often see risky behaviours such as driving and playing in dangerous water.

Recent floods, however, brought home the reality of the threat. Few could forget images of frightened families being winched off roofs by helicopter, water rushing from spilling dams and everyday people rescuing their neighbours.

The NSW government on Wednesday released an independent report into this year’s floods. It examined flooding from February to April and again in July – mostly around the Northern Rivers, Sydney’s Hawkesbury-Nepean and the central to north coasts.

The report contained troubling statistics, including:

- nine people tragically died

- 7,700 people sought emergency accommodation

- 14,600 homes were damaged

- 5,300 homes were left uninhabitable.

Releasing the report, NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet said up to 40,000 Western Sydney residents risked flood evacuation by 2040, if flood conditions similar to those in July were repeated and no mitigation action was taken.

The inquiry revealed a central theme: the need for a renewed and stronger emphasis on sustained disaster preparedness. Otherwise, as the report noted, the emergency response becomes harder:

Preparedness is discussed in relation to emergency management and our natural and built environment. But an important component of preparedness is at a personal or family level. Failure to prepare at this level makes preparations at other levels more difficult and expensive.

‘Don’t Worry. Your House Won’t Get Wet’

Our current research is examining the experiences of those affected by this year’s floods to gather insights on preparedness and response. Participants can take part in an interview, a survey or both.

Our interviews are already providing useful insights. They include the possibility that prior experience of flood, and the well-meaning reassurances of others, can hinder preparations. As one respondent said:

the house, having been built on a mound, has never been flooded and that’s why my neighbour said, ‘Don’t worry. Your house won’t get wet. It’s never got wet in 70 years’. But this was unprecedented.

With another wet summer likely, interviewees are starting to see major flooding as a “new normal” rather than a once-in-a-lifetime experience. This is causing them to question the future of their communities. As another respondent told us:

that’s the part that I’m struggling with now is that it feels like it’s unviable to live here because there’s no security, and when you take away people’s security, your life tends to unravel.

We hope our research will influence policy and practice on flood preparation, community engagement and risk messaging, and shed light on more permanent changes required.

Be Prepared

So what should you do if flooding is forecast and you need to evacuate? Here’s what experts recommend:

identify the safest route to your nearest safe location and leave well before roads flood

move vehicles, valuables, outdoor equipment, garbage and poisons to higher locations

enact safety plans for pets and other animals

take medications and identification with you

tell friends, family and neighbours of your plans

know where to go for information. Monitor alerts and stay aware of changing situations

keep your mobile phone charged and have at least half a tank of fuel in your vehicle

turn off electricity, gas, and water at the mains before you leave.

Of course, flood preparation should not be left until the last minute. Now is a good time to think about what might happen in the months ahead. Things you can do now include:

clean up outside and inside, move or secure items that could float or create a hazard

move valued possession to higher places in your home

pack an emergency bag and keep it at the ready

consider which friends or family you might stay with if needed.

For further advice, head to the website of your state’s emergency service agencies.

Thinking Long-Term

Climate change will exacerbate floods and other natural hazards. Communities must be supported to prepare as best they can.

More permanent measures are also needed, such as land buybacks to move people out of flood-prone areas. And importantly, planning systems must ensure we don’t keep building on floodplains.

Our approach to disaster readiness will continue to change. Already, experts are providing advice on matters such as emotional preparedness and recovery in the aftermath.

One thing is clear: in the face of the increasing disaster threat, temporary and seasonal preparations are no longer enough. ![]()

Mel Taylor, Associate Professor, Macquarie University and Katharine Haynes, Honorary Senior Research Fellow, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Drought: five ways to stop heavy rains washing away parched soil

When William Blake described England’s “green and pleasant land” in his poem Jerusalem, he was actually writing during a prolonged drought. Two centuries later, much of Europe is withering under successive heatwaves amid one of the most extreme droughts ever recorded.

The latest satellite image of England captured by Nasa shows not a green and pleasant land but one which is brown and parched. Under all that dry vegetation is sun-baked, dusty and desiccated soil.

Heavy rain and thundery showers are now forecast for much of the UK. No doubt the promise of a good downpour will please farmers, for whom the drought has been particularly punishing. Bizarrely though, heavy rain may not be what their thirsty soil needs right now.

A soil normally acts like a sponge which soaks up moisture when it rains. Having been baked for weeks by intense heat with little respite, soil surfaces have hardened.

As a result, the soil’s infiltration capacity (the maximum rate at which soils can absorb moisture) has diminished. If rain falls at such an intensity that this rate is exceeded, the water will run off the soil surface, potentially triggering flash floods and other hazards downslope.

When heavy rain falls, tonnes of soil can be eroded into the flow and rushed out of farm gates. There, it is washed into rivers, and spat out to sea in a brown plume that can occasionally be seen from space.

Likewise, flash floods can leave thousands of households with thick carpets of sand, silt and clay. Cleaning up after extreme rainfall can drain wallets very quickly, but there is a larger and longer-term cost.

Soil erosion is a major threat to the resilience of the environment. Proactive measures to curb erosion are essential to ensure soils continue supporting food production, sustaining habitats and biodiversity, cycling nutrients and safely storing the carbon fuelling climate change.

Here are five options for preventing soil running off the land.

1. Don’t Leave Soils Bare

A bare soil is particularly vulnerable to erosion. Extreme heat can make some harvests come early, leaving soils bare for longer. Farmers can grow cover crops such as brassicas, legumes and grasses to protect soils from being exposed between periods of crop production.

As well as shielding the soil from rain splash, some cover crops can suppress weeds and fungal diseases, replenish carbon and offer food and habitat to wildlife.

2. Adapt Tillage Practices

Soil tillage (digging, stirring and overturning it) is one of the most practised methods of preparing the land for growing crops. But tilling the soil too vigorously can damage its internal structure.

A healthy soil has a continuous network of pores and channels capable of storing and transporting air and water. Lining this network are mineral and organic aggregates. Maintaining the soil’s structure is vital, not only for bolstering its resistance to erosion, but for enhancing how much water can infiltrate it.

Shifting towards less intensive tillage practices – reduced or zero tillage farming – has been shown to be effective at curbing soil erosion. Ploughing across slopes rather than down them can reduce it even further.

3. Watch Out For Overgrazing

Grazing livestock like cattle can maintain grassland habitats and support native wildlife, but overgrazing can be a problem. If vegetation is stripped from the land faster than it can naturally recover, soils are left bare and prone to erosion.

Overgrazing can also compact the soil, making it less effective at soaking up moisture and increasing the likelihood that water will run off the surface.

4. Consider Terracing Steep Slopes

Steep slopes funnel water downhill fast. Building a series of level steps into the slope where food can be grown, a practice known as terracing, is an effective engineering solution.

Hillslope terracing has been adopted by farmers for millennia, and can be particularly good at reducing water runoff and sediment erosion, especially if regularly maintained. Levelling the slope can also help water infiltrate the soil and increase how much water it can hold.

5. Grow A Buffer Strip

For fields bordering rivers and streams, planting buffer strips of vegetation on the boundary with the watercourse can offer multiple benefits beyond reducing soil erosion.

Comprised of grass and shrubs, buffer strips increase the roughness of the land which slows the water running off it. Planting trees in buffer strips can help stabilise riverbanks, shade livestock and reduce the runoff of agricultural chemicals into rivers. As well as combating soil erosion, buffer strips feed and shelter pollinating insects, enriching a farm’s biodiversity.

Be Proactive Not Reactive

It only takes a second to open an umbrella and protect yourself from a downpour. Protecting soil from erosion demands more proactive measures.

These five recommendations can build a soil’s resistance to erosion, particularly during the spells of heavy rain which often follow heatwaves. If implemented and maintained, these strategies can have lasting additional benefits for soil fertility, biodiversity and slowing climate change.![]()

Dan Evans, 75th Anniversary Research Fellow, Soil and Agrifood Institute, Cranfield University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

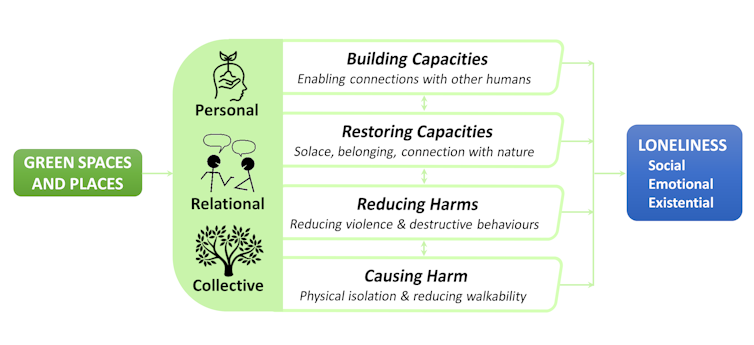

1 in 4 Australians is lonely. Quality green spaces in our cities offer a solution

One in four Australian adults feel lonely, and the impacts can be dire. Loneliness increases our risks of depression, diabetes, dementia, self-harm and suicide. But likening it to a disease and proposals to treat it with a pill miss the point: we’ve been building for loneliness over many decades and decision-makers have been asleep at the wheel.

Having studied the issue, we view loneliness as largely a product of our environment – what we call a “lonelygenic environment” – not a disease or a problem with any particular individual. So what is this “lonelygenic environment”?

Over decades, our cities have become sprawling low-density agglomerations. Many places are too far to walk from home. Short errands are routinely done by car, erasing opportunities to stop and chat with locals.

Large-scale felling of street trees has not only obliterated natural shade, but severed our connection with the “more than human” world. Car traffic dominates residential roads, which are also clogged with parked cars.

We have lost the people-friendly streets that we once used for regularly gathering, playing and celebrating with neighbours. No wonder we now know so few by name.

If the determinants of loneliness are largely environmental, so too must be the solutions. Yet we hear so little about this.

How Much Difference Can Green Space Make?

In a previous Conversation article, we suggested investing in public green space is part of the solution to the epidemic of loneliness. The article was based on our longitudinal study that reported a greening target of 30% local landcover could cut the odds of becoming lonely by a quarter. Among people living alone, who tend to be more vulnerable to loneliness, green space cut those odds by up to a half.

But how can green space reduce loneliness? That’s the focus of our new review of studies from around the world. Two-thirds of the studies found green space potentially protected people against loneliness.

Our review identified multiple pathways for reducing loneliness. These included:

- building capacities for connection with community

- restoring our sense of belonging and connection with nature

- reducing harms, such as violence, that may otherwise lead to loneliness.

The Quality Of The Green Space Matters

During the COVID-19 pandemic we undertook a nationally representative survey and found the odds of connecting with neighbours were five times higher for people who visited high-quality green space than for those who didn’t or couldn’t.

Related benefits were also much stronger if green spaces were higher quality. For example, exercise and relief from stress were both more commonly reported by people visiting higher-quality green spaces.

Quality was defined by participants’ views on things such as access, aesthetics, facilities, incivilities (e.g. litter, disrepair) and safety. Perceptions are important because the qualities of a green space need to resonate for people to visit them.

Regular visits to green spaces foster attachment and belonging. These spaces permit quiet contemplation in solitude, but also bring people together and connect people with nature. They become revered as settings for gatherings, bonding, cheering and shared memory-making.

By encouraging relaxation and playfulness – which can be frowned upon in other settings – green spaces may also enable connection for people who otherwise find it difficult, such as those with highly introverted personalities.

The psychologically restorative benefits of green space are now well-documented. Green spaces such as healing gardens can serve as therapeutic landscapes, offering refuge and respite for those experiencing loneliness, which can stem from some form of trauma. While usually provided for patients, these settings might also offer sanctuaries for health professionals experiencing burnout.

The bottom line is that higher-quality green space maximises opportunities for both social connection and health. While our previous research and other studies highlight inequities in access to green space, we must pay even more attention to inequities in the quality of green space.

Consult Communities To Get It Right

This may all sound like we think the impacts of green space are universally positive; we don’t. For instance, many studies in countries such as Denmark, Poland and New Zealand report that some people with disabilities, who are already vulnerable to loneliness, face significant barriers to visiting green spaces and may feel “out of place” within them.

Other research indicates that the creation or regeneration of green spaces in communities may be associated with disempowerment and dispossession, by making nearby housing less affordable.

In other words, a nearby green space that is highly attractive and a source of joy for some people may for others be a symbol of processes that aggravate loneliness and perpetuate misery.

That is why community views on the design of green space really matter. Consultation is key to ensure everyone feels meaningfully engaged in the process.

Our program of work, and our new review in particular, shows green space qualities depend on the context, preferences and needs of local residents. It is clear we need local networks of green spaces that provide something of value for everyone.

Finally, the process of urban greening itself can help counter loneliness by empowering communities to actively participate in creating and maintaining local green spaces. This has been done successfully over decades by the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney’s Community Greening program. By bringing people together to create green spaces, the garden has been quietly showing us the solution to our lonelygenic environment all along.![]()

Xiaoqi Feng, Associate Professor in Urban Health and Environment; NHMRC Career Development Fellow, UNSW Sydney and Thomas Astell-Burt, Professor of Population Health and Environmental Data Science, NHMRC Boosting Dementia Research Leadership Fellow, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia may be heading for emissions trading between big polluters

Could Australia soon have a form of emissions trading? Yes, if Labor’s much-anticipated paper on fixing Australia’s mediocre emissions-reduction framework, released today, is any guide.

At present, Australia relies on the controversial safeguard mechanism to encourage big emitters such as fossil fuel power plants and manufacturers to reduce their pollution. This framework – alongside the Emissions Reduction Fund – was introduced during the Coalition years to reduce carbon dioxide pollution at low cost.

The problem is, it didn’t work. Emissions from large polluters have remained high since it was introduced in 2016. As the discussion paper states:

Emissions limits, known as baselines, have allowed business-as-usual operations and aggregate emissions from Safeguard facilities to grow.

Labor’s discussion paper flags ways to make the mechanism work as intended – most significantly by letting companies sell credits created by cutting emissions by more than they are required to. Companies finding it harder to slash emissions can buy these. Creating this market would effectively create a very useful carbon currency.

You might think this sounds abstract. It’s not. Fixing this mechanism would have a major impact on our future emissions – and the likelihood of reaching our committed emission goals. Getting this right matters.

So What Is The Safeguard Mechanism And Why Does It Matter?

The safeguard mechanism is a framework to control emissions from large polluters – defined as those emitting more than 100,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent annually.

This includes industries such as electricity generation, mining, and oil and gas extraction.

It works by giving each facility a benchmark level of emissions they are not allowed to exceed.

If a facility does exceed their benchmark, the regulator gives them a few easy options: reduce emissions, ask for their benchmark to increase, or buy and surrender Australian Carbon Credit Units. These credits come from someone else’s emissions reductions, which the original polluter has to pay for.

The problem is the current safeguard mechanism is not fit for purpose.

As I’ve previously pointed out, the system is easily gamed. Many high-polluting firms have simply asked for larger benchmarks – and often got them. You can see the incentive – asking for a larger, “better fitting” benchmark is the cheapest option of all, requiring absolutely no change on the company’s part.

This is the fundamental flaw: there is no economic incentive for large polluters to cut their emissions.

Better systems already exist in other countries. For instance, large polluters in the United States and European Union are targeted using pollution markets that have robust economic incentives.

In such schemes, companies that find it very expensive to reduce pollution can buy pollution credits from the market. Alternatively, companies that find it cheap to reduce emissions can sell their credits and make money. Labor’s new discussion paper draws heavily on these successful schemes.

Even better, the government can raise serious revenue from this market by initially auctioning off pollution credits. It’s a win-win: polluters pay and gain a strong incentive to reduce emissions, and the government obtains much-needed revenue at a time when budgets are stretched from the pandemic.

The public funds raised can be significant: the carbon market set up by 12 states in the eastern US has auctioned off pollution allowances since 2008, raising A$5.45 billion to date.

If we want to reach Labor’s target of cutting emissions by 43% (relative to 2005 levels) over the coming eight years, we need a fully functional market-based approach.

So What Are The Proposed Changes?

The paper sets out the main proposals for developing the safeguard mechanism, including how to set a baseline of emissions for polluters (and how this should decline over time), the use of offsets, and the introduction of trading.

Trading would be the most significant change. Some companies will pursue emissions reduction with greater vigour – or may find it easier to do so than those in harder-to-abate sectors such as aluminium smelting or steel-making. The ability to sell these avoided emissions rewards these companies. The companies buying the credits have an incentive to cut emissions over time to avoid this cost.

Another proposal is to allow banking and borrowing of these credits over time. This would allow firms reducing emissions today to save credits for the future or, if needed, borrow some from the future.

The Big Question: Will It Work?

From an economist’s perspective, this is good news.

Allowing firms to trade credits will make the safeguard mechanism more cost-effective and create incentives to actually cut emissions – something lacking in the old version.

But it could work even better.

Under the current proposal, companies in the scheme cannot trade with firms outside it. This cuts the number of market participants and could limit the cost-effectiveness of the scheme. Labor should look at widening the scope and creating a fully fledged market.

And while banking and borrowing pollution credits has been shown to work reasonably well in other countries, we know it has to be managed well.

If the scheme isn’t properly managed, companies could borrow credits and simply never pay them back. Banked carbon credits could actually lead to higher emissions in the future, when companies draw down on them.

In the EU this became a real concern when the stockpile of banked allowances grew too large. In response, the European scheme’s regulator had to remove them from the market. The Australian government must learn from this and design the scheme carefully.

But overall? Take this as good news. It is a step towards a goal that has long been out of reach: a well-functioning pollution market.![]()

Ian A. MacKenzie, Associate Professor in Economics, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Should we bring back the thylacine? We asked 5 experts

In a newly announced partnership with Texas biotech company Colossal Biosciences, Australian researchers are hoping their dream to bring back the extinct thylacine is a “giant leap” closer to fruition.

Scientists at University of Melbourne’s TIGRR Lab (Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research) believe the new partnership, which brings Colossal’s expertise in CRISPR gene editing on board, could result in the first baby thylacine within a decade.

The genetic engineering firm made headlines in 2021 with the announcement of an ambitious plan to bring back something akin to the woolly mammoth, by producing elephant-mammoth hybrids or “mammophants”.

But de-extinction, as this type of research is known, is a highly controversial field. It’s often criticised for attempts at “playing God” or drawing attention away from the conservation of living species. So, should we bring back the thylacine? We asked five experts.

![]()

Signe Dean, Science + Technology Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How to deal with fossil fuel lobbying and its growing influence in Australian politics

Will climate action undermine Australia’s democracy? This question might not be as outlandish as it seems.

A recent investigation details a campaign by the car industry to have its (low) voluntary standards on fuel efficiency legislated into national standards. This campaign fits into a broader pattern of lobbying by the fossil fuel industry to hinder effective climate action and highlights the importance of democratic integrity in addressing the climate crisis as well as the urgent need for robust regulation of lobbying.

The Fossil Fuel Lobby And Climate Inaction

University of Melbourne professor Ross Garnaut has observed that “(e)missions-intensive industries have invested heavily to influence climate change policy since the early days of discussion of these issues”.

We see the influence of these investments in various ways:

- the resources industry is by far the biggest donor in Australian politics

- the $22 million advertising campaign by mining companies against the Rudd government’s resource super profits tax was such a success that it’s now become routine for industry groups to threaten a “mining tax style campaign” every time they don’t get their way with government

- fossil fuel industry employees and lobbyists have included former Liberal Party, National Party and ALP ministers.

Rise Of The ‘Greenhouse Mafia’

Marian Wilkinson’s book The Carbon Club provides a compelling account of how a network of climate-science sceptics, politicians and business leaders brought about decades of climate inaction in Australia.

Under the Howard government, climate change policy was determined by fossil fuel lobbyists who likened themselves to organised crime through a self-styled label — the greenhouse mafia.

The group has contributed to the outsized role the fossil fuels industry has in steering government policy. Perhaps most importantly, fossil fuel companies have played an instrumental role in ousting two out of the six prime ministers Australia has had since 2007; Kevin Rudd and Malcolm Turnbull.

The term, “policy capture” is described by the OECD to mean when public decisions over policies are consistently directed away from the public interest towards a specific interest, leading to inequalities and undermining democratic values, economic growth, and trust in government. The use of the phrase in this context has a certain validity.

The Lobbying Risks Of Climate Action

Paradoxically, the risks associated with fossil fuel lobbying increase with higher levels of climate action.

Effective climate action will mean increased regulation of fossil fuel industries, such as more stringent emission standards for the largest greenhouse emitters under the ALP’s Powering Australia plan. Under the plan, substantial amounts of public funds will go towards climate action.

As a result, the fossil fuel industries and other sections of the community will naturally seek to influence government climate decisions. That in itself is not undemocratic – fossil fuel industries have a legitimate role in influencing government policy.

However, what is undemocratic is their disproportionate influence and how it is often wielded behind closed doors.

Regulatory Failures Of Federal Lobbying System

Lobbying regulation in Australia is particularly scant. It currently takes the form of a public lobbyist register and a code of conduct.

The secrecy and lack of integrity around fossil fuel lobbying stems directly from the shortcomings of federal lobbying regulation. This lack of transparency also includes:

- lobbying coverage that has been confined to commercial lobbyists, who only comprise 20% of the lobbyist population, excluding other “repeat players” such as in-house lobbyists

- Dismal disclosure obligations that require only the name and contact details of the lobbyist and the client they are representing. There is a vacuum of knowledge about when lobbyists are contacting government officials and over what issues.

Enforcing violations is also a huge concern. In 2018, the Commonwealth Auditor-General found the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, which oversaw the federal lobbyist register, did not take any action against lobbyists despite identifying at least 11 possible breaches.

The Way Forward

Three essential reforms will make federal lobbying regulation more effective, while also assisting with effective climate action.

First, coverage under federal lobbying regulation should extend to both commercial lobbyists and in-house lobbyists. Following the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption’s (ICAC) Operation Eclipse, the NSW government will implement lobbying laws that will regulate these two classes of lobbyists (as is done in Canada and the United States).

Second, there should be greater transparency of lobbying activity by requiring:

- lobbyists to disclose every lobbying contact (such as in Queensland, Canada and Scotland)

- ministers, senior ministerial advisers and senior public servants to provide monthly disclosures of who has contacted them and why. Currently, Queensland discloses ministerial diaries, while NSW will disclose diaries of ministers and MPs

- the establishment of an independent regulator or commissioner to regularly monitor and take action in these matters if needed, such as the NSW government has committed to do.

Safeguarding democracy is imperative in the climate crisis and to the functioning of government overall. Robust lobbying regulation is an essential measure to ensure that all are protected.![]()

Joo-Cheong Tham, Professor, Melbourne Law School, The University of Melbourne and Yee-Fui Ng, Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

After floods will come droughts (again). Better indicators will help us respond

Neal Hughes, Deakin UniversitySince late 2020, the La Niña climate pattern has led to two years of above-average rainfall across much of Australia, and severe floods in parts of the country.

In areas spared the flooding, this rainfall has been good news for farmers, with improved conditions and high prices driving production and profits to record highs.

But the next drought is rarely too far away. For a reminder, we only need to look overseas, where the same La Niña weather system is combining with climate change to produce severe droughts in the United States, eastern Africa and South America.

Unfortunately, drought can be difficult to define and measure. Determining whether a region or farm is “in drought” is a longstanding and complex problem, which remains important to our future drought response.

Drought Is About More Than Rainfall

For a long time, Australia’s standard measure of drought has been rainfall. But while rainfall indicators are easy to produce and interpret, they can be a poor measure of a farm’s prospects.

For one thing, the impact of drought depends on the timing of rain.

Even when the year’s total rainfall is okay, if most of it arrives at the wrong time of year (such as outside the crop season) it can have the same impact as a drought.

Temperatures are also increasingly important, with record heat waves having an important effect in recent years.

The story gets more complicated still when droughts affect the prices of inputs to farms. For example, during the 2018-19 drought many dairy farms were impacted by high hay and water prices, even where they received rain.

Measuring Farm Impacts

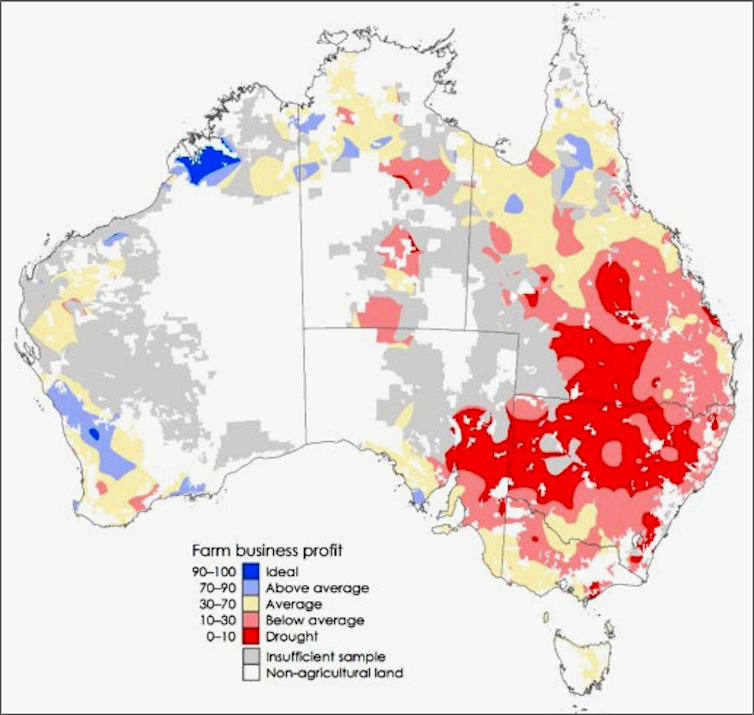

In response, researchers including myself at the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) have developed a new drought indicator based on predictions of farm financial outcomes, with some advantages over measures based on only rain.

In some cases it presents a very different picture.

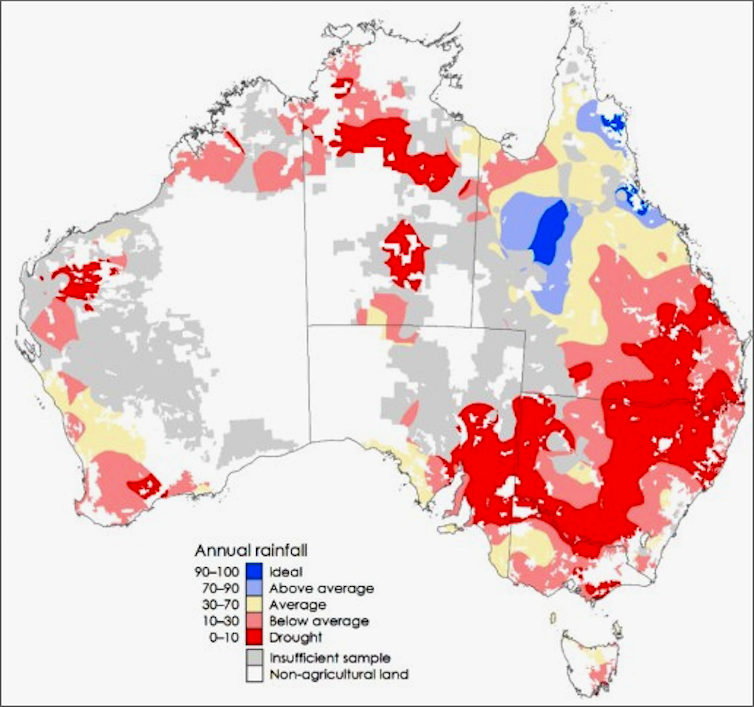

In the example below, for 2018-19, the indicator shows more severe impacts in parts of New South Wales than the rainfall model (because low rainfall was compounded by high temperatures and input prices), and less severe impacts in Western Australia (partly because of high grain prices resulting from shortages on the east coast).

Rain-based indicator:

Model-based indicator:

Drought Declarations Are Mattering Less

Since the early 2000s, drought policy has evolved away from in-drought support of farm businesses to an approach that emphasises preparedness and resilience, making explicit drought “declarations” less common.

While this change has been welcome, it also led to a reduced focus on drought impact measurement (with the exception of some state-level systems).

But as recent droughts have shown, information on the extent and severity of drought impacts is still very important.

For one, it can help governments anticipate and prepare for increased demand for farm programs such as the Farm Household Allowance or the Rural Financial Counselling Service.

It can also help to better target resources for community, animal welfare or mental health drought impacts.

Better indicators can also support the development of new insurance products such as index-based weather insurance.

Such products are more likely to take off where indexes (and therefore payouts) can closely match real-world outcomes.

Early Warnings Are Mattering More

While there is some evidence climate change has exacerbated recent droughts in Australia, there remains much uncertainty over the longer term effects.

Regardless, the potential for more extreme weather events is generally increasing the importance of early warning systems.

ABARES is working with the CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology to develop a Drought Early Warning System that will use this new indicator and a range of other tools to translate weather data into estimates of likely farm impacts.

Predicting these impacts remains very difficult, with challenges both in weather forecasting (particularly on monthly or longer time scales), and in translating these forecasts into agricultural outcomes.

But any improvements we can make will help us better respond to what the future has in store.![]()

Neal Hughes, Adjunct Associate Professor, Centre for Regional and Rural Futures, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Soviet Union once hunted endangered whales to the brink of extinction – but its scientists opposed whaling and secretly tracked its toll

Every year, an estimated 13 million people go whale-watching around the world, marveling at the sight of the largest animals ever to inhabit Earth. It’s a dramatic reversal from a century ago, when few people ever saw a living whale. The creatures are still recovering from massive industrial-scale hunting that nearly wiped out several species in the 20th century.

The history of whaling shows how humans have wreaked careless havoc on the ocean, but also how they can change course. In my new book, “Red Leviathan: The Secret History of Soviet Whaling,” I describe how the Soviet Union was central both to this deadly industry and to scientific research that helps us understand whales’ recovery.

From Wood To Steel And Bad To Worse

At the start of the 20th century, it seemed whales might gain a reprieve after years of hunting. The era of whaling from sail boats, depicted in such memorable detail by Herman Melville in “Moby-Dick,” had nearly wiped out slow, fat species like right and bowhead whales, and also wreaked substantial harm to sperm whales.

In the 1800s, U.S. whalers sailed without restraint or hindrance into every corner of the world’s oceans, including waters around Russia’s Siberian empire. There, tsarist officials watched in helpless rage as Americans slaughtered whales upon which many of the region’s Indigenous peoples relied.

In the 1870s, petroleum began to replace whale oil as a fuel. With few catchable whales remaining, the industry appeared to be near its end. But whalers found new markets. Through hydrogenation – a chemical process that can be used to turn liquid oils into solid or semi-solid fats – manufacturers were able to transform smelly whale products into odorless margarine for human consumption.

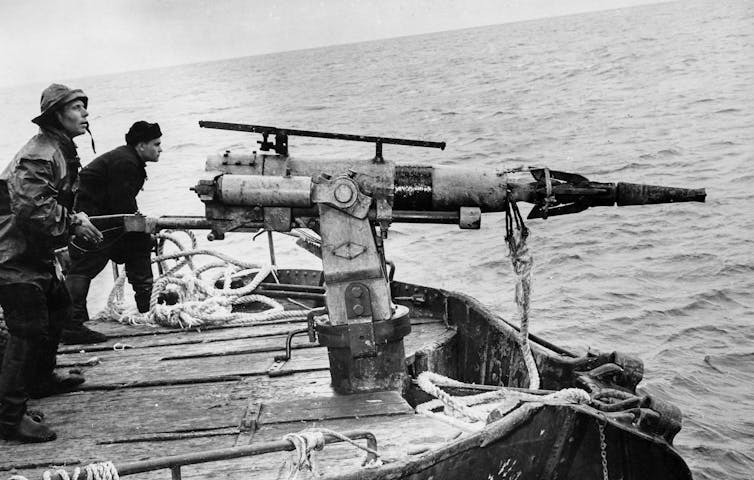

Around the same time, Norwegians invented the explosive harpoon, which killed whales more efficiently than hand-thrown versions, and the stern slipway, which allowed whale carcasses to be processed on board ships. Along with diesel engines and steel hulls, these technologies enabled whalers to target previously untouched species in once-inaccesible locations, such as the Antarctic.

Late To The Party, Late To Leave

As mechanized whaling gained force in the 1920s and ‘30s, Norwegian, British and Japanese whalers cut through populations of blue, fin and humpback whales on a scale that is hard to believe today. In what scientists once thought was the peak catch year, 1937, over 63,000 large whales were killed and processed.

World War II briefly suspended this slaughter, which many governments were starting to realize threatened the survival of some whale species. In 1946, whalers, statesmen and scientists created the International Whaling Commission in hopes of heading off a return to disastrous prewar levels of whaling.

That same year, the USSR joined the IWC and took control over a former Nazi whaleship, which it renamed the Slava, or Glory. No one suspected the central role the country would play in the most disastrous two decades of whales’ long history on Earth.

The Madness Of Modern Whaling

Despite the IWC’s best intentions, postwar catches rose quickly. By the mid-1950s, even longtime whalers had to admit that big whales were becoming too scarce for their industries to be profitable. All nations except Japan began to ponder the end of whaling.

It thus came as a shock when the Soviet Union announced in 1956 that it planned to build seven new “floating factories” – gigantic industrial processing ships, accompanied by fleets of smaller “catcher” boats that would scour the oceans for whales.

Soviet whale scientists were as stunned as observers elsewhere. These biologists and oceanographers had been watching the decline from ships and from their labs in the Fisheries Ministry and Academy of Sciences since the 1930s.

Instead of supporting the fleet expansion, they argued forcefully that whales stood on the brink of extinction, and whaling should decrease radically, not expand. This was how the Soviet planned economy was meant to work: Science, not profit, would help guide economic decisions, letting planners know how much could be extracted from the natural world and when to stop.

But Soviet officials were determined to finally catch whales on a large scale, as Western nations had done for so long. The Fisheries Ministry ignored its scientists’ recommendations and built five of the seven planned floating factories over the next decade.

By the 1960s, the Soviet Union was the world’s largest whaling nation. Whalers such as the legendary captain Aleksei Solyanik were celebrated as superstars, comparable to astronauts like Yuri Gagarin.

But the scientists had been right: Many whales species were nearly gone. To produce large catches, Solyanik and other captains decided to ignore international quotas and secretly targeted the most endangered whale species, including blue, humpback and fin whales in the Antarctic and the North Pacific.

In 1961, for example, Soviet fleets killed 9,619 rare humpbacks south of New Zealand, while reporting only 302 to the IWC. This was only a portion of their global catch, which the Soviet Union continued to underreport for years. Driven by Moscow’s demands for ever-increasing production, whalers worked at reckless speed, wasting much of the fat and meat taken from the dead whales. It is doubtful the industry was ever profitable.

Thanks to Soviet scientists who preserved some records of these illegal kills and to subsequent work by other scholars, it now appears likely that the Soviet Union killed around 550,000 whales after World War II while reporting only 360,000. We now know that global whale harvesting peaked in 1964, not 1937, with a total of 91,783 whales killed – about 40% by Soviet whalers.

Not Quite Extinct

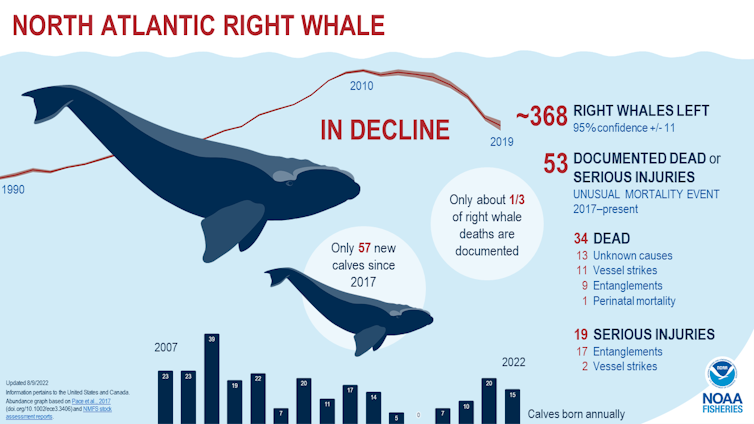

By the 1970s, populations of large whales had dwindled to insignificance. Many observers were sure extinction was inevitable. But momentum for whale conservation was growing.

The U.S. listed blue, fin, sei, sperm and humpback whales under the law that preceded the Endangered Species Act in 1970, then continued to protect them under that law, enacted in 1973. Whales also received protection in U.S. waters under the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Thanks to pressure from environmentalists and its own citizens, the Soviet Union ended its whaling industry in 1987. The country accepted a global moratorium on commercial whaling, which remains in force today with only three holdouts: Norway, Iceland and Japan.

Whale numbers almost immediately began to rebound. Humpback whales were especially successful, but populations of bowhead, fin and sperm whales also expanded in the near absence of commercial whaling. However, some species, notably North Atlantic right whales, remain endangered or critically endangered.

In one of the greatest conservation successes, Eastern Pacific gray whales are today estimated to have returned to pre-exploitation abundance, and may actually be reaching the limits of what their primary foraging grounds in the Bering Sea can support. And in 2018 and 2019, German scientists and researchers from the BBC observed and filmed fin whales feeding around the Antarctic peninsula in vast pods that recalled the way the ocean must have looked before the 20th century.

Thanks to the Russian scientists who opposed their country’s disastrous whaling expansion and kept its records, we know how many whales were lost in the 20th century. That information can also help scientists, governments and conservationists judge whales’ remarkable but far from complete recovery.![]()

Ryan Jones, Associate Professor of History, University of Oregon

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Influential oil company scenarios for combating climate change don’t actually meet the Paris Agreement goals, our new analysis shows

Several major oil companies, including BP and Shell, periodically publish scenarios forecasting the future of the energy sector. In recent years, they have added visions for how climate change might be addressed, including scenarios that they claim are consistent with the international Paris climate agreement.

These scenarios are hugely influential. They are used by companies making investment decisions and, importantly, by policymakers as a basis for their decisions.

But are they really compatible with the Paris Agreement?

Many of the future scenarios show continued reliance on fossil fuels. But data gaps and a lack of transparency can make it difficult to compare them with independent scientific assessments, such as the global reviews by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

In a study published Aug. 16, 2022, in Nature Communications, our international team analyzed four of these scenarios and two others by the International Energy Agency using a new method we developed for comparing such energy scenarios head-to-head. We determined that five of them – including frequently cited scenarios from BP, Shell and Equinor – were not consistent with the Paris goals.

What The Paris Agreement Expects

The 2015 Paris Agreement, signed by nearly all countries, sets out a few criteria to meet its objectives.

One is to ensure the global average temperature increase stays well below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 F) compared to pre-industrial era levels, and to pursue efforts to keep warming under 1.5°C (2.7 F). The agreement also states that global emissions should peak as soon as possible and reach at least net zero greenhouse gas emissions in the second half of the century. Pathways that meet these objectives show that carbon dioxide emissions should fall even faster, reaching net zero by about 2050.

Scientific evidence shows that overshooting 1.5°C of warming, even temporarily, would have harmful consequences for the global climate. Those consequences are not necessarily reversible, and it’s unclear how well people, ecosystems and economies would be able to adapt.

How The Scenarios Perform

We have been working with the nonprofit science and policy research institute Climate Analytics to better understand the implications of the Paris Agreement for global and national decarbonization pathways – the paths countries can take to cut their greenhouse gas emissions. In particular, we have explored the roles that coal and natural gas can play as the world transitions away from fossil fuels.

When we analyzed the energy companies’ decarbonization scenarios, we found that BP’s, Shell’s and Equinor’s scenarios overshoot the 1.5°C limit of the Paris Agreement by a significant margin, with only BP’s having a greater than 50% chance of subsequently drawing temperatures down to 1.5°C by 2100.

These scenarios also showed higher near-term use of coal and long-term use of gas for electricity production than Paris-compatible scenarios, such as those assessed by the IPCC. Overall, the energy company scenarios also feature higher levels of carbon dioxide emissions than Paris-compatible scenarios.

Of the six scenarios, we determined that only the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero by 2050 scenario sketches out an energy future that is compatible with the 1.5°C Paris Agreement goal.

We found this scenario has a greater than 33% chance of keeping warming from ever exceeding 1.5°C, a 50% chance of having temperatures 1.5°C warmer or less in 2100, and a nearly 90% chance of keeping warming always below 2°C. This is in line with the criteria we use to assess Paris Agreement consistency, and also in line with the approach taken in the IPCC’s Special Report on 1.5°C, which highlights pathways with no or limited overshoot to be 1.5°C compatible.

Getting The Right Picture Of Decarbonization

When any group publishes future energy scenarios, it’s useful to have a transparent way to make an apples-to-apples comparison and evaluate the temperature implications. Most of the corporate scenarios, with the exception of Shell’s Sky 1.5 scenario, don’t extend beyond midcentury and focus on carbon dioxide without assessing other greenhouse gases.

Our method uses a transparent procedure to extend each pathway to 2100 and estimate emissions of other gases, which allows us to calculate the temperature outcomes of these scenarios using simple climate models.

Without a consistent basis for comparison, there is a risk that policymakers and businesses will have an inaccurate picture about the pathways available for decarbonizing economies.

Meeting the 1.5°C goal will be challenging. The planet has already warmed about 1.1°C since pre-industrial times, and people are suffering through deadly heat waves, droughts, wildfires and extreme storms linked to climate change. There is little room for false starts and dead-ends as countries transform their energy, agricultural and industrial systems on the way to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions.![]()

Robert Brecha, Professor of Sustainability, University of Dayton and Gaurav Ganti, Ph.D. Student in Geography, Humboldt University of Berlin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

America Bay Track Walk - photos by Joe Mills

An Aquatic June: North Narrabeen - Turimetta - Collaroy photos by Joe Mills

Angophora Reserve Angophora Reserve Flowers Grand Old Tree Of Angophora Reserve Falls Back To The Earth - History page

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek by Joe Mills

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Pittwater's Lone Rangers - 120 Years of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase and the Men of Flowers Inspired by Eccleston Du Faur

Pittwater's Parallel Estuary - The Cowan 'Creek

Resolute Track at West Head by Kevin Murray

Resolute Track Stroll by Joe Mills

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Seagull Pair At Turimetta Beach: Spring Is In The Air!