inbox and environment news: Issue 592

July 30 - August 5, 2023: Issue 592

National Tree Day 2023: 3 Sites For Our Area This Year - Planting Out Takes Place Sunday July 30 At Avalon Beach, Duffys Forest, Curl Curl

.jpg?timestamp=1679635455680)

Photo: A J Guesdon

Council and Planet Ark are inviting local residents to dig in and do something good for nature and their community as part of National Tree Day 2023.

National Tree Day is a great opportunity to maintain and enhance our beautiful environment for our local wildlife as well as ensuring the region continues to be a great place to live and getting all the benefits that come from spending time outdoors..

Over 26 million trees have been planted by volunteers since 1996 as part of the program and we are excited for the community to support the goal of getting another million native plants in the ground this year.

Schools Tree Day (July 28) and National Tree Day (July 30) are Australia’s largest annual tree-planting and nature care events, with plantings taking place across the country on the last weekend of July. Each year, around 300,000 people volunteer their time to engage in activities that encourage greater understanding of the natural world and how we can protect it.

National Tree Day event is taking place in three locations in our area on Sunday July 30th. Native trees, shrubs and grasses will be planted at the sites. Residents can register to volunteer at the event via the National Tree Day website at treeday.planetark.org/find-a-site/.

Details of each run below

“Our research clearly shows the many benefits that time outdoors in nature has for our physical and mental health, our children’s development, the liveability of our communities and the robustness of local ecosystems,” said Planet Ark co-CEO Rebecca Gilling.

“With the simple action of planting a tree you can help cool the climate, provide homes for native wildlife and make your local community a happier and healthier place to live.”

National Tree Day is an initiative organised by Planet Ark in partnership with major sponsor Toyota Australia and its Dealer Network. For more information and to find events in your local area, please visit treeday.planetark.org.

National Tree Day 2023: Local sites

Avalon Beach: Palmgrove Road

In the grass area between Dress Circle Road and Bellevue Ave, Avalon

DATE & TIME: Sunday, 30 July 2023, 10:00am to 2:00pmSite Organiser: Michael Kneipp

RSVP Contact: Michael Kneipp, 1300 434 434

Suitable for Children: Yes

Accessible for Wheelchairs: No

VOLUNTEER INFORMATION: Please wear long pants, long sleeve shirt, sturdy shoes, gloves and a hat. Everyone is invited to help us regenerate this important wildlife corridor with native plants. Make Avalon a cooler, greener and more connected place for our community and wildlife.

WHAT'S PROVIDED?: Gloves, Tools and equipment for planting, Watering cans / buckets, Refreshments, BBQ

Volunteer at this site: https://treeday.planetark.org/find-a-site/volunteer/10028078

Duffys Forest Residents Association

DATE & TIME: Sunday, 30 July 2023, 9:00am to 1:00pm

LOCATION: 13 Namba Road, Duffys Forest

Site Organiser: Jennifer Harris

RSVP Contact: Jennifer Harris, 0408512060

Suitable for Children: Yes

Accessible for Wheelchairs: Yes

DIRECTIONS: You can enter the site at the end of Namba road. Proceed through two large metal gates, to picnic area to sign on for the event.

VOLUNTEER INFORMATION: Volunteers must wear suitable clothing & protective gear including covered shoes, gloves and a hat. It is proposed that volunteers plant up to 600 indigenous native tube stock in degraded areas of the park to create additional canopy species, establish ground cover, reduce weed invasion and to improve biodiversity & wildlife habitat. The activity is located in an iconic park, formerly known as Waratah Park, the home of "Skippy". The event will be supervised by a qualified bush regenerator & aims to inspire & educate participants to become custodians and actively care for our unique environment. Last year we planted over 450 tube stock with 35 volunteers in just over 3 hours. These tube stock have thrived due to ongoing maintenance and watering by volunteers.

WHAT'S PROVIDED?: Gloves, Tools and equipment for planting, Watering cans / buckets, Snacks, Refreshments, BBQ

Volunteer at this site: https://treeday.planetark.org/find-a-site/volunteer/10027702

Curl Curl

DATE & TIME: Sunday, 30 July 2023, 10:00am to 2:00pm

Location: Griffin Road, North Curl Curl

VOLUNTEER INFORMATION: Please wear long pants, long sleeve shirt , sturdy shoes, gloves and a hat. There are also public transport and cycling options. Everyone is invited to help us regenerate this important wildlife corridor with native plants. Make Curl Curl a cooler, greener and more connected place for our community and wildlife. Please wear long pants, long sleeve shirt , sturdy shoes, gloves and a hat.

Enter via the car park or footpath on the Southern side of the Greendale Creek bridge. Look for our Northern Beaches Council Marquees.

Site Organiser: Michael Kneipp

RSVP Contact: Michael Kneipp, 1300 434 434

Suitable for Children: Yes

Accessible for Wheelchairs: No

Volunteer at this site: https://treeday.planetark.org/find-a-site/volunteer/10028073

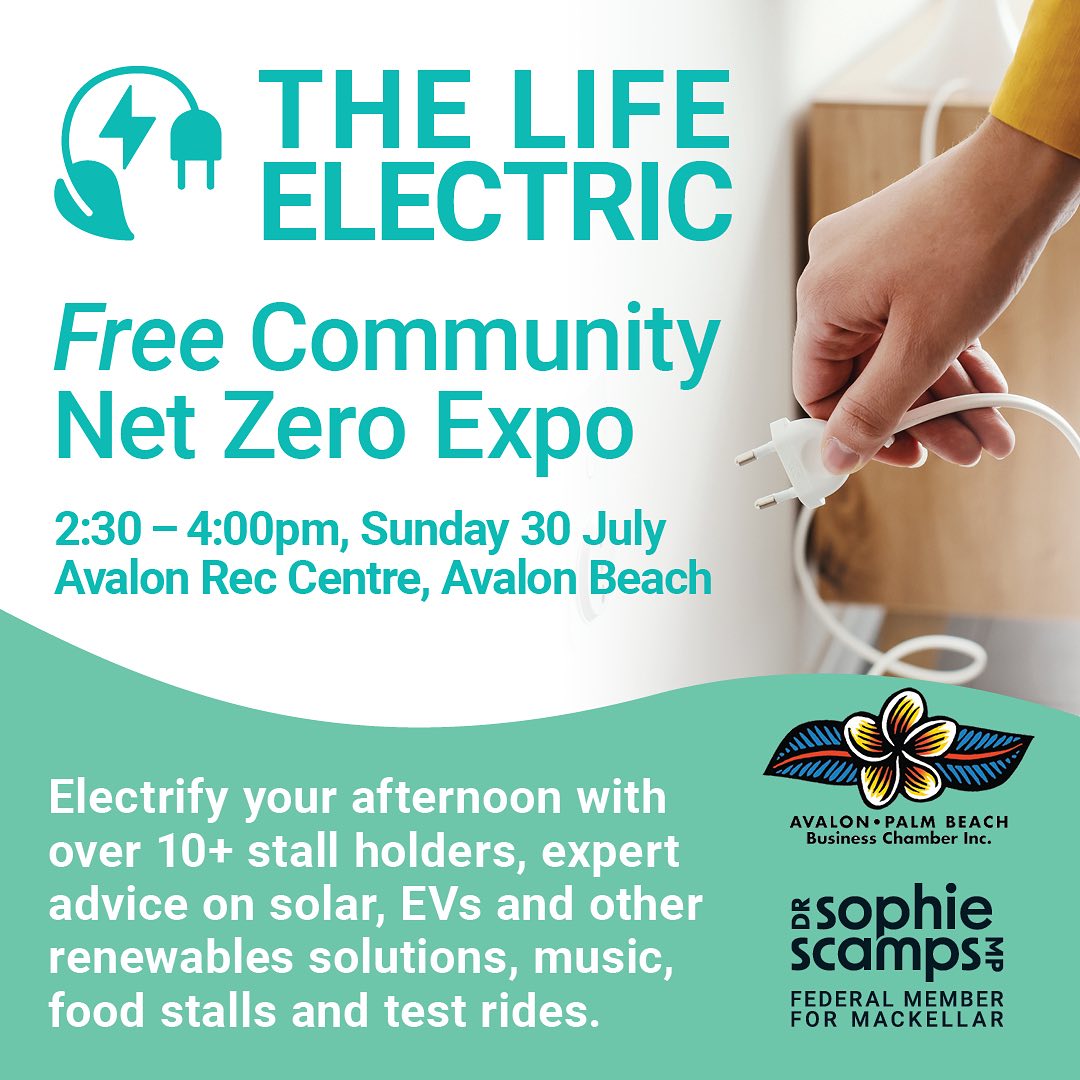

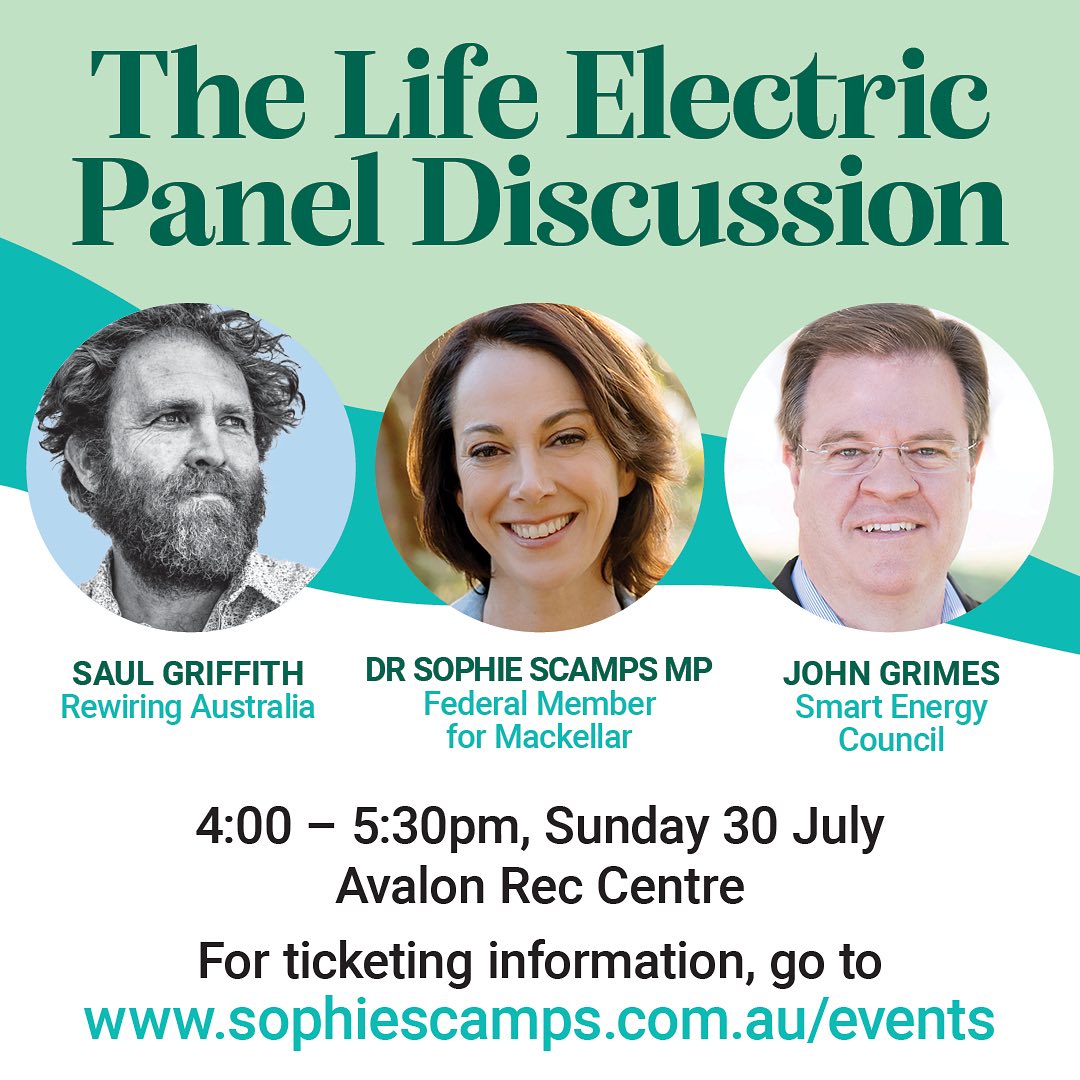

The Life Electric Expo And Forum: July 30th At Avalon Rec. Centre

The Life Electric Community Expo is hosted by Avalon Palm Beach Business Chamber Inc. Entry is free with 10+ stalls, expert advice, food, music and test rides. You can also purchase tickets to the live panel featuring Saul Griffith and John Grimes.

Book your tickets ($10) at the link here: https://www.trybooking.com/events/landing/1076483

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Dee Why Lagoon Beach Side Clean Up, 30th Of July, 2023, At 10am

Come and join us for our family friendly July clean up, in Dee Why Lagoon on the 30th at 10am. We meet in the grass area close to the council car park, and the surf life saving club at the north end of Dee Why. Please note that this is a different meeting point to where we were last time.

We have gloves, bags, and buckets, and grabbers. We're trying to remove as much plastic and rubbish as possible before it enters the water. Some of us can focus on the bush area and sandy/rocky areas, and others can walk along the water and even clean up in the water (at own risk). We will clean up until around 11.15, and after that, we will sort and count the rubbish so we can contribute to research by entering it into a marine debris database. The sorting and counting is normally finished around noon, and we'll often go for lunch together at our own expense. We understand if you cannot stay for this part, but are grateful if you can. We appreciate any help we can get, no matter how small or big.

No booking required - just show up on the day - we will be there no matter what weather. We're a friendly group of people, and everyone is welcome to this family friendly event. It's a nice community - make some new friends and do a good deed for the planet at the same time.

For everyone to feel welcome, please leave political and religious messages at home - this includes t-shirts with political campaign messages.

Message us on our social media or send us an email if you are lost. All welcome - the more the merrier. Please invite your friends too! All details in our Facebook event, Instagram or on our website.

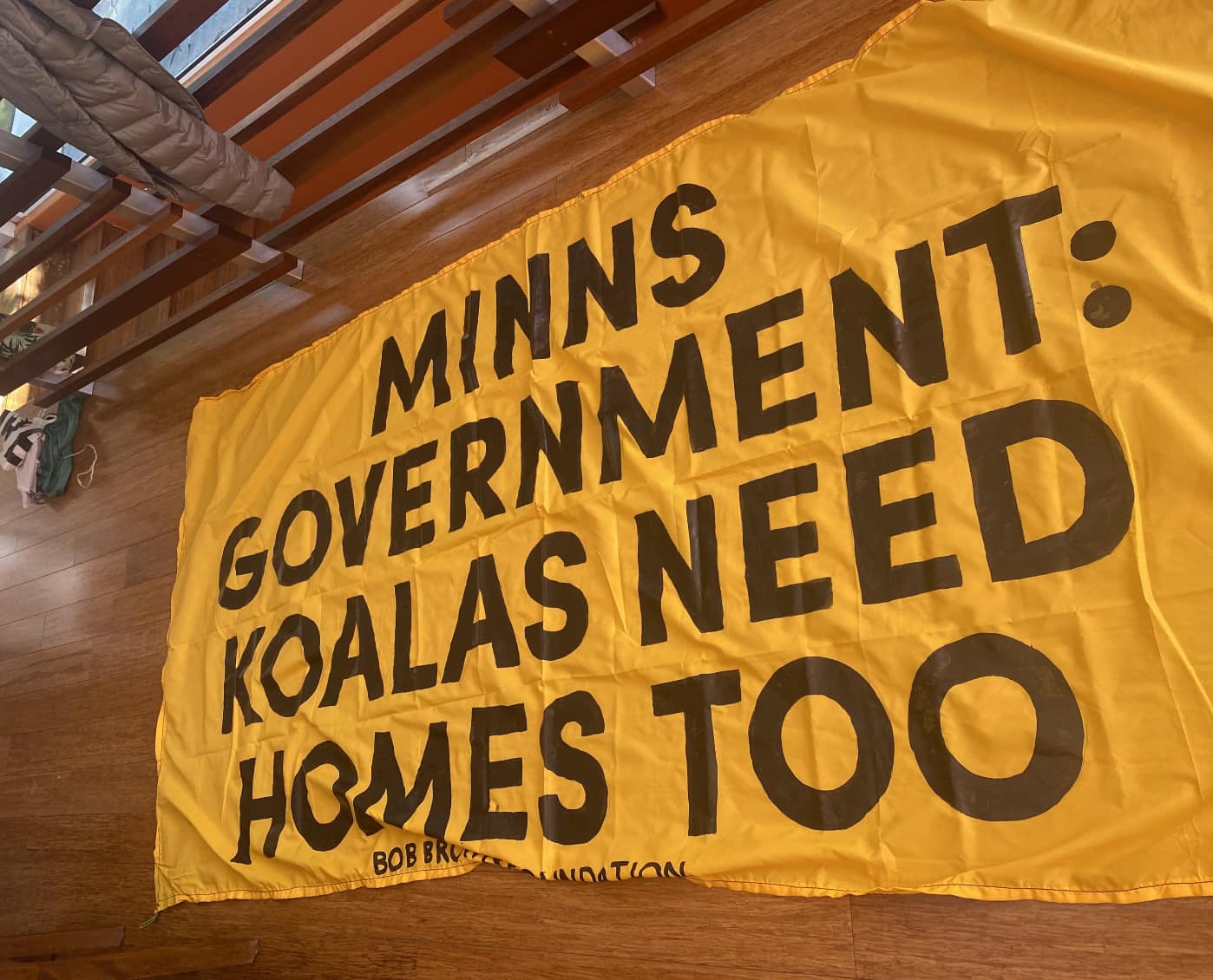

Koala Vigil: Opposite Parliament House At Martin Place On Thursday 3rd August 12-1 Pm

Endangered 4-Month Old Monk Seal Pup Found Dead In Hawaii Was Likely Caused By Dog Attack Officials Say

Turtle Conservation Program Named Eureka Prize Finalist

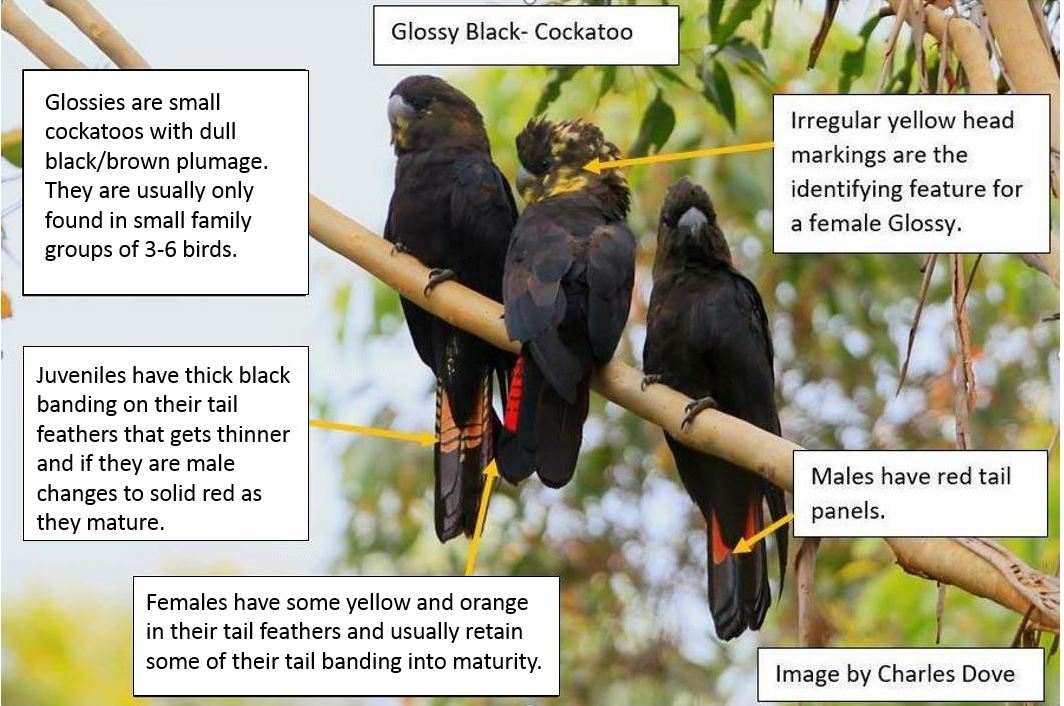

Seen Any Glossies Drinking Around Nambucca, Bellingen, Coffs Or Clarence? Want To Help?: Join The Glossy Squad

- a female bird (identifiable by yellow on her head) begging and/or being fed by a male (with plain black/brown head and body and unbarred red tail feathers)

- a lone adult male, or a male with a begging female, flying purposefully after drinking at the end of the day.

- One-hundred brush-tailed mulgaras released onto Dirk Hartog Island

- Eighth species translocated as part of ground-breaking ecological restoration project

- Return to 1616 project is protecting populations of unique Western Australian wildlife

Endangered Dibblers Destined For Dirk Hartog Island National Park

- 24 Dibblers will be released at Dirk Hartog Island National Park for the first time

- Since 1997 over 900 Dibblers bred at Perth Zoo have been released into the wild

WA's New Strategy To Crackdown On Feral Cats In Nation First

- New five-year plan to manage invasive feral cats across Western Australia

- Strategy first of its kind to be implemented by a State Government in the nation

- $7.6 million investment to expand feral cat management in 2023-24 State Budget

- Fight against feral cats ramps up to protect native wildlife and biodiversity

New Victorian Homes To Go All Electric From 2024

Get Off The Gas: Victoria Is Quitting Gas, NSW Should Follow Suit

New Trail In Yallock-Bulluk Set To Stun Visitors

Australia's First Commercial Hydrogen Refuelling Station Opens At Port Kembla

Port Kembla is now home to Australia's first commercial hydrogen refuelling station for zero emissions heavy road vehicles, in a major breakthrough towards de-carbonising the region’s 7000 heavy vehicles, the NSW Government has announced.

Port Kembla is now home to Australia's first commercial hydrogen refuelling station for zero emissions heavy road vehicles, in a major breakthrough towards de-carbonising the region’s 7000 heavy vehicles, the NSW Government has announced.NSW Landholders To Be Rewarded For Private Land Conservation

Tasmanian ALP Continues To Back Wildlife Slaughter And Forest Destruction

Rockliff Liberal Tasmanian Government States It Is 'Rock-Solid In Our Support For Tasmania’s Forestry Sector'

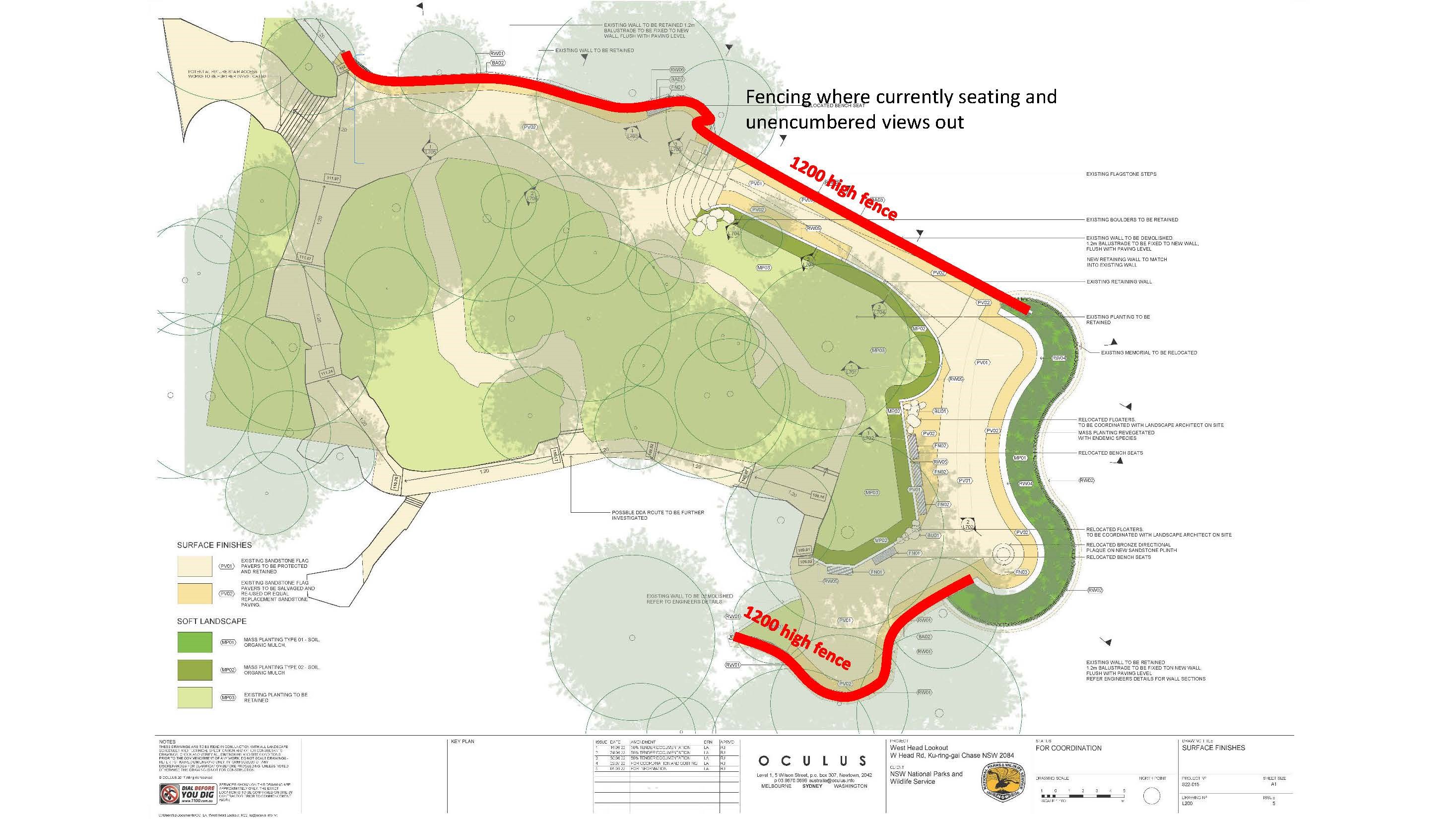

Areas Closed For West Head Lookout Upgrades

NPWS advise that the following areas are closed from Monday 22 May to Thursday 30 November 2023 while West Head lookout upgrades are underway:

NPWS advise that the following areas are closed from Monday 22 May to Thursday 30 November 2023 while West Head lookout upgrades are underway:

- West Head lookout

- The loop section of West Head Road

- West Head Army track.

Vehicles, cyclists and pedestrians will have access to the Resolute picnic area and public toilets. Access is restricted past this point.

The following walking tracks remain open:

- Red Hands track

- Aboriginal Heritage track

- Resolute track, including access to Resolute Beach and West Head Beach

- Mackeral Beach track

- Koolewong track.

The West Head lookout cannot be accessed from any of these tracks.

Image: Visualisation of upcoming works, looking east from the ramp towards Barrenjoey Head Credit: DPE

Time Of Burrugin

Cold and frosty; June-July

Echidna seeking mates - Burringoa flowering - Shellfish forbidden

This is the time when the male Burrugin (echidnas) form lines of up to ten as they follow the female through the woodlands in an effort to wear her down and mate with her. It is also the time when the Burringoa (Eucalyptus tereticornis) starts to produce flowers, indicating that it is time to collect the nectar of certain plants for the ceremonies which will begin to take place during the next season. It is also a warning not to eat shellfish again until the Boo'kerrikin (Acacia decurrens, commonly known as black wattle or early green wattle) blooms.

Eucalyptus tereticornis, commonly known as forest red gum, blue gum or red irongum, is a species of tree that is native to eastern Australia and southern New Guinea. It has smooth bark, lance-shaped to curved adult leaves, flower buds in groups of seven, nine or eleven, white flowers and hemispherical fruit.

Eucalyptus tereticornis was first formally described 1795 by James Edward Smith in A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland from specimens collected in 1793 from Port Jackson by First Fleet surgeon and naturalist John White. The specific epithet (tereticornis) is from the Latin words teres (becoming tereti- in the combined form) meaning "terete" and cornu meaning "horn", in reference to the horn-shaped operculum.

Habitat tree: Sclerophyll Forest.

Food tree: Natural stands are an important food tree for koalas and a wide variety of nectar-eating birds, fruit bats and possums.

Eucalyptus tereticornis buds, capsules, flowers and foliage, Rockhampton, Queensland. Photo: Ethel Aardvark

Shelly Beach Echidna

Photos by Kevin Murray, taken late May 2023 who said, ''he/she was waddling across the road on the Shelly Beach headland, being harassed not so much by the bemused tourists, but by the Brush Turkeys who are plentiful there.''

Shelly Beach is located in Manly and forms part of Cabbage Tree Bay, a protected marine reserve which lies adjacent to North Head and Fairy Bower.

From the D'harawal calendar, BOM

D'harawal

The D'harawal Country and language area extends from the southern shores of Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour) to the northern shores of the Shoalhaven River, and from the eastern shores of the Wollondilly River system to the eastern seaboard.

Bush Turkeys: Backyard Buddies Breeding Time Commences In August - BIG Tick Eaters - Ringtail Posse Insights

PNHA Guided Nature Walks 2023

Our walks are gentle strolls, enjoying and learning about the bush rather than aiming for destinations. Wear enclosed shoes. We welcome interested children over about 8 years old with carers. All Welcome.

So we know you’re coming please book by emailing: pnhainfo@gmail.com and include your phone number so we can contact you if weather is doubtful.

The whole PNHA 2023 Guided Nature Walks Program is available at: http://pnha.org.au/test-walks-and-talks/

Red-browed finch (Neochmia temporalis). Photo: J J Harrison

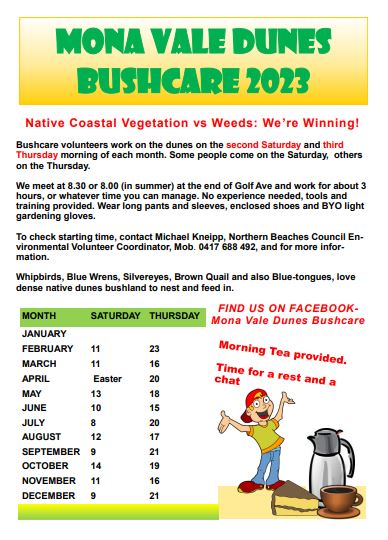

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Hottest July Ever Signals ‘Era Of Global Boiling Has Arrived’ Says UN Chief

Warming Trend In Asia Set To Cause More Disruption: UN Weather Agency

Seismic Testing + Exploration Drilling In Western Australia, Victorian, Tasmanian, Northern Territory Waters - Past And Currently Open For Feedback Proposals

NOPSEMA's Compliance Strategy 2023 Released

Why can’t we just tow stranded whales and dolphins back out to sea?

Vanessa Pirotta, Macquarie UniversityOn Tuesday night, a pod of almost 100 long-finned pilot whales stranded itself on a beach on Western Australia’s south coast. Over the course of Wednesday, more than 100 parks and wildlife staff and 250 registered volunteers worked tirelessly to try to keep alive the 45 animals surviving the night.

They used small boats and surf skis to try to get the pilot whales into deeper water. Volunteers helped keep the animals’ blowholes above water to prevent them drowning, and poured water on them to cool them down.

Our rescue efforts were, sadly, unsuccessful. The animals (actually large ocean-going dolphins) able to be towed or helped out to deeper water turned around and stranded themselves again, further down the beach. Sadly, they had to be euthanised.

Unfortunately, towing whales and dolphins is not simple. It can work and work well, as we saw in Tasmania last year, when dozens of pilot whales were rescued. But rescuers have to have good conditions and a fair dash of luck for it to succeed.

Rescuing Beached Whales Is Hard

When we try to rescue stranded whales and dolphins, the goal is to get them off the sandbars or beach, and back into deep water.

Why is it so difficult? Consider the problem. First, you have to know that a pod has beached itself. Then, you have to be able to get there in time, with people skilled in wildlife rescue.

These animals are generally too big and heavy to rely on muscle power alone. To get them out far enough, you need boats and sometimes tractors. That means the sea conditions and the slope of the beach have to be suitable.

Often, one of the first things rescuers might do is look for those individuals who might be good candidates to be refloated. Generally, these are individuals still alive, and not completely exhausted.

If rescuers have boats and good conditions, they may use slings. The boats need to be able to tow the animals well out to sea.

Trained people must always be there to oversee the operation. That’s because these large, stressed animals could seriously injure humans just by moving their bodies on the beach.

There are extra challenges. Dolphins and whales are slippery and extremely heavy. Long-finned pilot whales can weigh up to 2.3 tonnes. They may have never seen humans before and won’t necessarily know humans are there to help.

They’re out of their element, under the sun and extremely stressed. Out of the water, their sheer weight begins to crush their organs. They can also become sunburnt. Because they are so efficient at keeping a comfortable temperature in the sea, they can overheat and die on land. Often, as we saw yesterday, they can’t always keep themselves upright in the shallow water.

And to add to the problem, pilot whales are highly social. They want to be with each other. If you tow a single animal back out to sea, it may try to get back to its family and friends or remain disorientated and strand once again.

Because of these reasons – and probably others – it wasn’t possible to save the pilot whales yesterday. Those that didn’t die naturally were euthanised to minimise their suffering.

Successful Rescues Do Happen

Despite the remarkable effort from authorities and local communities, we couldn’t save this pod. Every single person working around the clock to help these animals did an amazing job, from experts to volunteers in the cold water to those making cups of tea.

But sometimes, we get luckier. Last year, 230 pilot whales beached themselves at Macquarie Harbour, on Tasmania’s west coast. By the time rescuers could get there, most were dead. But dozens were still alive. This time, conditions were different and towing worked.

Rescuers were able to bring boats close to shore. Surviving pilot whales were helped into a sling, and then the boat took them far out to sea. Taking them to the same location prevented them from beaching again.

Every Stranding Lets Us Learn More

Unfortunately, we don’t really know why whales and dolphins strand at all. Has something gone wrong with how toothed whales and dolphins navigate? Are they following a sick leader? Are human-made undersea sounds making it too loud? Are they avoiding predators such as killer whales? We don’t know.

We do know there are stranding hotspots. Macquarie Harbour is one. In 2020, it was the site of one of the worst-ever strandings, with up to 470 pilot whales stranded. Authorities were able to save 94, drawing on trained rescue experts.

We will need more research to find out why they do this. What we do know suggests navigational problems play a role.

That’s because we can divide whales and dolphins into two types: toothed and toothless. Whales and dolphins with teeth – such as pilot whales – appear to beach a lot more. These animals use echolocation (biological sonar) to find prey with high-pitched clicks bouncing off objects. But toothless baleen whales like humpbacks (there are no dolphins with baleen) don’t use this technique. They use low-frequency sounds, but to communicate, not hunt.

So – it is possible to save beached whales and dolphins. But it’s not as easy as towing them straight back to sea, alas.

The Conversation thanks 10-year-old reader Grace Thornton from Canberra for suggesting the question that gave rise to this article.![]()

Vanessa Pirotta, Postdoctoral Researcher and Wildlife Scientist, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

An expert explains the stranding of 97 pilot whales in WA and their mysterious ‘huddling’ before the tragedy

Kate Sprogis, The University of Western AustraliaSad scenes are unfolding in Western Australia after a pod of pilot whales became stranded on a beach late on Tuesday. According to the latest reports, 51 of the whales have died. Some 46 remain beached and authorities are working desperately to get them back out to sea.

Pilot whale strandings unfortunately occur in WA, and other Australian states, from time to time. In recent years they have also occurred in New Zealand and Scotland. But this stranding is unusual because of the behaviour the whales exhibited prior to becoming beached.

The pod of long-finned pilot whales began congregating in the ocean off Cheynes Beach on Monday evening. They remained in a “huddle” on Tuesday, raising fears a stranding was imminent.

I am a marine biologist who specialises in marine mammals. I am based at the University of Western Australia’s Albany campus, about 70 kilometres from where the stranding occurred. Sadly, the chances of survival for the remaining whales is very low – and time is fast running out.

Understanding Pilot Whales

There are two species of pilot whales: short-finned (which live mainly in tropical and warm-temperate regions) and long-finned (generally found in colder waters). As the name suggests, the long-finned pilot whales have longer pectoral fins than their counterparts.

The pilot whales stranded at Cheynes Beach are long-finned. They are generally found offshore, in the deep open ocean. We rarely see them close to the coast. This makes the species hard to study.

Pilot whales are, however, known to inhabit Bremer Canyon, a very deep ocean area 70 kilometres off the WA coast.

What Happened At Cheynes Beach?

The group of whales was spotted swimming in shallow waters at Cheynes Beach late on Monday. An official from the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions called me on Tuesday morning, and asked about the strange huddling behaviour. I was immediately concerned.

Healthy pilot whales do not form huddles, so something seemed very wrong. The department’s drone footage showed the pod was forming a very tight ball, then moving into a line, then back into the ball shape. And the pod was in very shallow coastal water, which is odd.

We suspected the behaviour was a precursor to a stranding. The department prepared its whale stranding kit and had officials on standby in case a stranding occurred. Unfortunately, it did.

By 4pm on Tuesday, almost 100 whales had beached themselves. Officials monitored them overnight. By Wednesday morning, 51 had died.

This is unsurprising. And sadly, the chance of survival for the remaining whales is very low. Cold, windy conditions means the whales are susceptible to hypothermia. And if they are already sick – as is sometimes the case with beached whales – this combination of factors can be fatal.

What’s more, whales are not used to the pressure of gravity we experience on land. When whales are stranded, their organs can collapse due to the weight of their own body.

In some cases, long-finned pilot whales have been known to survive after being stranded. But time is of the essence.

Why Did The Whales Beach Themselves?

In 2015, another pod of pilot whales beached itself in Bunbury, north of Albany. Sadly, 12 died. At the time, I and a colleague conducted necropsies – scientific examinations of animals after death – but the findings were inconclusive.

Whale strandings cannot be predicted and we do not know exactly why they occur. But in the case of pilot whales, their social behaviour offers some clues.

Pilot whales are similar to elephants in that they live in tight-knit family groups. It’s thought mass strandings may occur when the matriarch of the group is sick and swims into shallow water, and the others follow, or are “piloted”.

Whales may also become stranded due to an external stress. For example, whales use sound to communicate, navigate and search for food. Loud man-made underwater noises can disrupt this system.

What Next?

Officials at Cheynes Beach are trying to refloat the whales. Researchers are also taking biopsy samples and nasal swabs from the dead whales.

Experts will examine the swabs and samples, to try and understand more about this stranding event. I anticipate they will look for evidence of illness such as influenza or cetacean morbillivirus, as well as stress from underwater noise.

You might also be wondering what everyday people can do to help. If you observe marine mammals behaving unusually or getting stranded, alert authorities. And please stand aside to let authorities and other experts do their work. This is vital for the welfare of the animals and the safety of both helpers and bystanders.

Right now, I feel a bit helpless. I would like to be able to answer everyone’s primary question: why do pilot whales become stranded? It is a long-standing mystery in marine mammal science, and we don’t really know the answer.

More research is needed. Scientists need funding to attend mass strandings, collect and analyse samples and write up the findings. That gives us the best chance of piecing together this complicated puzzle.

Correction: An earlier version of this article said 87 whales were stranded, rather than 97.![]()

Kate Sprogis, Adjunct Research Fellow, UWA Oceans Institute, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

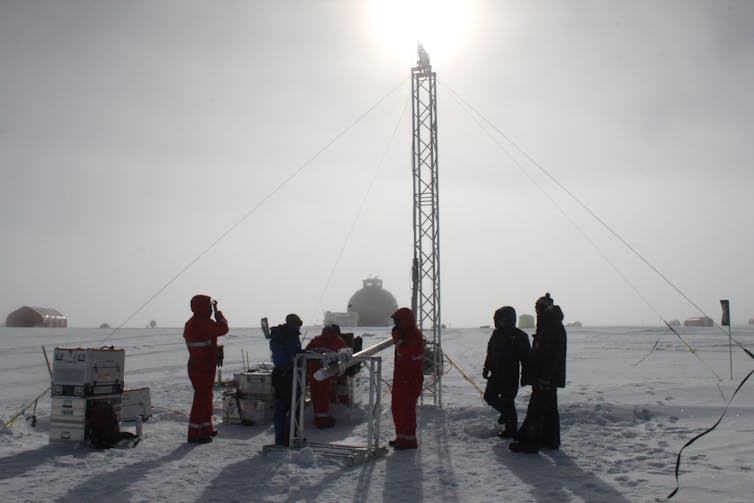

Gloomy Climate Calculation: Scientists Predict A Collapse Of The Atlantic Ocean Current To Happen Mid-Century

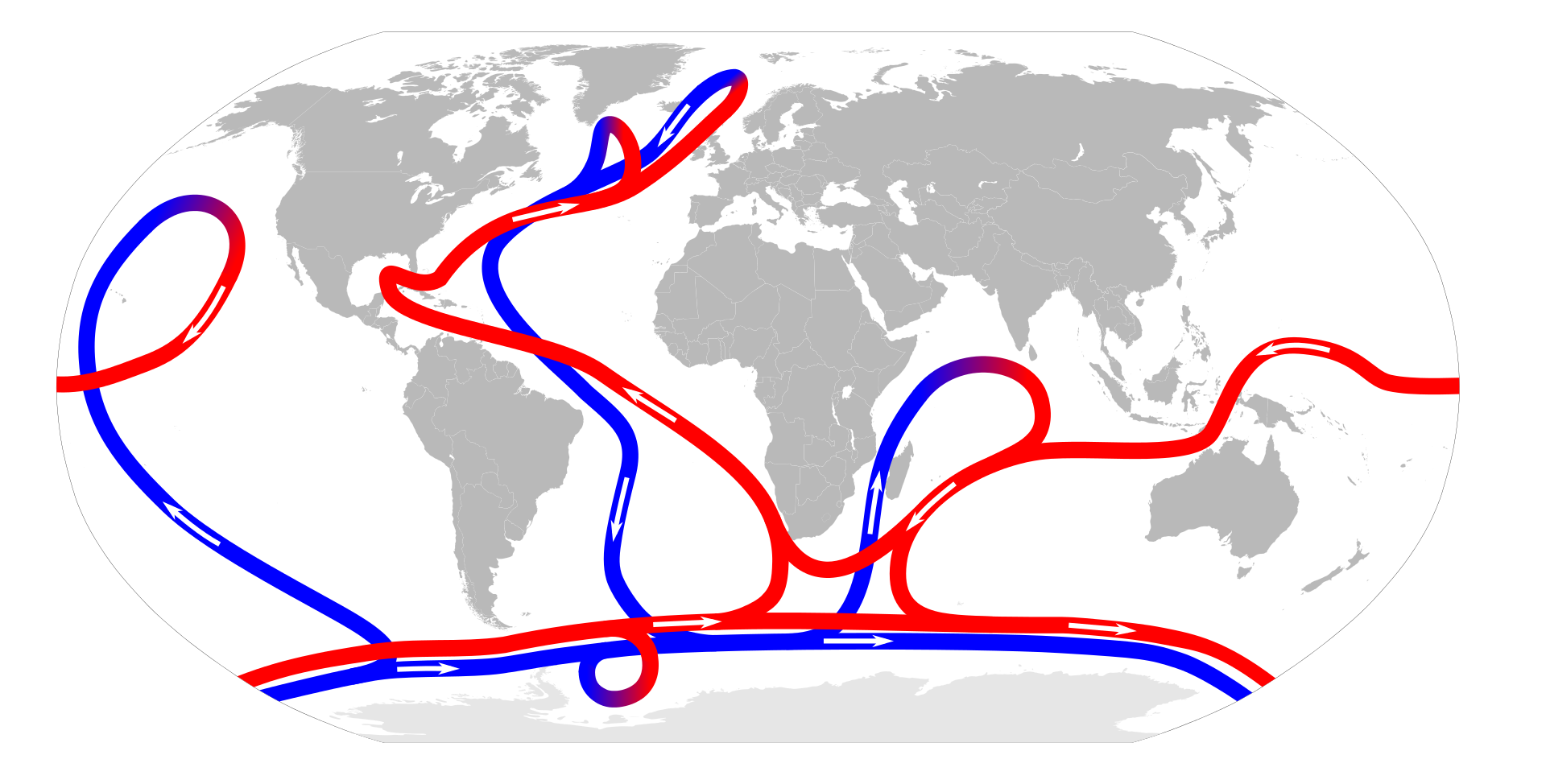

- The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is part of a global system of ocean currents. By far, it accounts for the most significant part of heat redistribution from the tropics to the northernmost regions of the Atlantic region -- not least to Western Europe.

- At the northernmost latitudes, circulation ensures that surface water is converted into deep, southbound ocean currents. The transformation creates space for additional surface water to be moved northward from equatorial regions. As such, thermohaline circulation is critical for maintaining the relatively mild climate of the North Atlantic region.

- The work is supported by TiPES, a joint-European research collaboration focused on tipping points of the climate system. The TiPES project is an EU Horizon 2020 interdisciplinary climate research project focused on tipping points in the climate system.

The Atlantic is at risk of circulation collapse – it would mean even greater climate chaos across Europe

Amid news of lethal heatwaves across the Northern Hemisphere comes the daunting prospect of a climate disaster on an altogether grander scale. New findings published in Nature Communications suggest the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, or Amoc, could collapse within the next few decades – maybe even within the next few years – driving European weather to even greater extremes.

The Amoc amounts to a system of currents in the Atlantic that bring warm water northwards where it then cools and sinks. It is a key reason why Europe’s climate has been stable for thousands of years, even if it’s hard to recognise this chaotic summer as part of that stability.

There is much uncertainty in these latest predictions and some scientists are less convinced a collapse is imminent. Amoc is also only one part of the wider Gulf Stream system, much of which is driven by winds that will continue to blow even if the Amoc collapses. So part of the Gulf Stream will survive an Amoc collapse.

But I have studied the links between Atlantic currents and the climate for decades now, and know that an Amoc collapse would still lead to even greater climate chaos across Europe and beyond. At minimum, it is a risk worth being aware of.

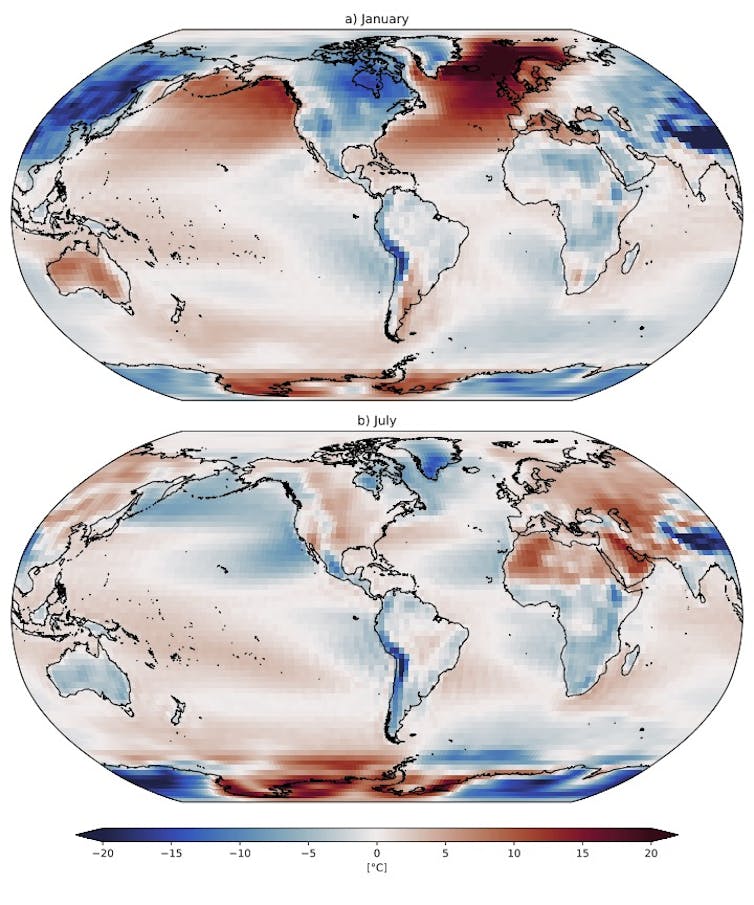

Amoc Helps Keep Europe Warm And Stable

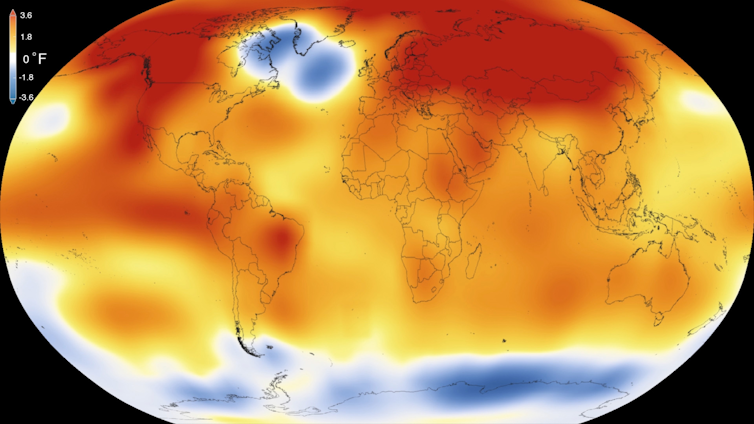

To appreciate how much Amoc influences the climate in the northeast Atlantic, consider how much warmer north Europeans feel compared to people at similar latitudes elsewhere. The following maps show how surface air temperatures depart from the average at each latitude and highlight patterns of warm and cool spots around the planet:

Most striking in the northern winter (January) is a red spot centred to the west of Norway where temperatures are 20°C warmer than the latitude average, thanks to Amoc. The northeast Pacific – and therefore western Canada and Alaska – enjoys a more modest 10°C warming from a similar current, while prevailing westerly winds mean the northwest Atlantic and northwest Pacific are much colder, as are the adjacent land masses of eastern Canada and Siberia.

The weather and climate of Europe, and northern Europe in particular, is highly variable from day to day, week to week and year to year, with competing air masses (warm and moist, cold and dry, and so on) gaining or losing influence, often guided by the high-altitude jet stream. Changes in weather and climate can be triggered by events located far away – and over the ocean.

How Ocean Temperatures Are Linked To Weather

Over recent years Europe has witnessed some particularly unusual weather, in both winter and summer. At the same time, peculiar patterns of sea surface temperatures have appeared across the North Atlantic. Across great swathes of the ocean from the tropics to the Arctic, temperatures have persisted 1°C-2°C above or below normal levels, for months or even years on end. These patterns appear to exert a strong influence on the atmosphere, even influencing the path and strength of the jet stream.

To an extent, we can attribute some of these sea surface temperature patterns to a changing Amoc, but it’s often not that straightforward. Nevertheless, the association of extreme seasons and weather with unusual sea temperatures might give us an idea of how a collapsed Amoc would unsettle the status quo. Here are three examples.

Northern Europe experienced successive severe winters in 2009/10 and 2010/11, subsequently attributed to a brief slowdown of the Amoc. At the same time heat had built up in the tropics, fuelling an unusually active June-November hurricane season in 2010.

In the mid 2010s a “cold blob” formed in the North Atlantic, reaching its most extreme in the summer of 2015 when it coincided with heatwaves in central Europe and was one of the only parts of the world cooler than its long-term average.

The cold blob looked suspiciously like the fingerprint of a weakened Amoc, but colleagues and I subsequently attributed this transient episode to more local atmospheric influences.

In 2017, the tropical Atlantic was again warmer than average and once again an unusually active hurricane season ensued, although the Amoc was not as clearly involved as 2010. Extensive warmth to the northeast in late 2017 may have sustained hurricane Ophelia, emerging around the Azores and making landfall in Ireland in October.

Based on just these few examples, we can expect that a more substantial reorganisation of North Atlantic surface temperatures will have profound consequences for the climate in Europe and beyond.

Larger ocean temperature extremes may alter the character of weather systems that are powered by heat and moisture from the sea – when and where temperatures rise beyond current extremes, Atlantic storms may grow more destructive. More extreme ocean temperature patterns may exert further influences on tropical hurricane tracks and the jet stream, sending storms to ever more unlikely destinations.

If the Amoc collapses we can expect larger extremes of heat, cold, drought and flooding, a range of “surprises” to exacerbate the current climate emergency. The potential climate impacts – on Europe in particular – should add urgency to our decision-making.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Robert Marsh, Professor of Oceanography and Climate, University of Southampton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate litigation is on the rise around the world and Australia is at the head of the pack

Jacqueline Peel, The University of MelbourneAustralians relish being at the top of international league tables in sport. But few would know we’re a global champion when it comes to using the courts to hold governments and companies to account on climate change.

A new report from the United Nations Environment Programme found a staggering 127 climate lawsuits in Australia. We’re second only to the United States on the number of cases and slightly ahead on a per capita basis. The count started in the 1990s and runs through to December 2022.

The research comes as the Northern Hemisphere suffers through unprecedented heatwaves and Antarctica experiences record sea ice retreat. And in Australia, we are bracing for an El Niño-charged summer.

The report says “climate litigation represents a frontier solution to change the dynamics of this fight” against climate change. And Australia, with our many cases and innovative tactics, is on the frontlines. But the report does not capture wins or losses. So while the case load is certainly growing and the field of law is maturing, it’s not yet clear what difference it will make in the long run.

What Is Climate Litigation?

Climate litigation describes a broad range of legal interventions brought to address climate change. The goal is generally to reduce emissions of climate-harming greenhouse gases (mitigation) or improve resilience in the face of climate impacts (adaptation).

These cases have become more common as the climate crisis has worsened and the gap grows between needed action and what governments and companies are actually delivering.

As the report states:

Climate change litigation provides civil society, individuals and others with one possible avenue to address inadequate responses by governments and the private sector to the climate crisis.

It’s an avenue that’s widely available. It can be accessed by many different groups including some of the most vulnerable. And it can be initiated using a wide range of laws, such as those protecting human rights, preventing misleading greenwashing, requiring corporate disclosures of climate risk or regulating the obligations of countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

This could make climate litigation a powerful tool for those disproportionately affected to demand and secure climate justice.

Australia As A Climate Litigation Hotspot

The US tops the climate litigation charts with 1,522 lawsuits filed. Australia comes second with 127.

But we’re in front on a per capita basis. The US figure works out to about 4.6 lawsuits per million people, compared to 4.8 lawsuits per million in Australia.

Australia’s status has been driven by several factors. These include our carbon-intensive economy and significant fossil fuel exports. Until recently, the dearth of climate policy nationally also encouraged some to resort to the courts for solutions. Australia also has a very active and engaged civil society which has tried a range of innovative legal arguments.

A key example in the report is the case brought by eight Torres Strait Islanders and six of their children to the UN Human Rights Committee.

In 2022, the committee delivered a landmark decision, finding the Australian government was violating its human rights obligations to Torres Strait Islanders through climate inaction. The decision delivered a number of legal world-firsts including the first time a country had been held responsible for its greenhouse gas emissions under international human rights law.

Australia has also been a pioneer in climate litigation against private sector entities, starting a wave of cases now building to a tsunami globally. Leading this trend are anti-greenwashing complaints.

The report singles out a case brought by the Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility against oil and gas company Santos. It alleges the company’s pledge of net zero emissions by 2040 is misleading and deceptive in violation of Australia’s consumer protection laws. This case is before the courts.

More Where That Came From

The report acknowledges it applies a “narrow approach” to defining climate litigation by excluding cases not sent to courts or quasi-judicial bodies, or which don’t feature climate change as a central issue.

As we’ve found in our Australian and Pacific Climate Change Litigation database, maintained by Melbourne Climate Futures, a broader lens yields even more climate cases. Between 2000-22, our database records 371 examples of Australian climate litigation.

In previous research we found most Australian cases do not yield court wins. For example, there have been many cases against coal mines but only a handful have actually stopped the mine going ahead.

How Do Lawsuits Help Fight The Climate Crisis?

Litigation is an important tool for advancing climate action and accountability. A report last year by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change considered climate litigation for the first time, finding some cases influenced the outcome and ambition of climate governance.

The latest report spells out ways individuals, communities and groups are using litigation to drive action. This includes efforts to:

enforce existing climate laws

ensure climate issues are widely integrated into planning and economic decision-making

force governments and companies to raise the ambition of their emissions reduction commitments

establish a link between climate change and human rights violations, and

seek compensation for climate harms.

Many cases put forward innovative legal arguments but are ultimately unsuccessful in getting the remedy they seek. One example is the 2021 Australian litigation by teenage climate activist Anjali Sharma and other young people against the federal environment minister, then Sussan Ley. Even where lawsuits do deliver a legal win, the report highlights potential “implementation challenges” when it comes to putting those judgements into action.

The report predicts where climate litigation might head next. This includes the potential for more cases addressing risks of climate displacement and migration, and consequences of climate-fuelled disasters such as the Black Saturday bushfires.

It also forecasts more cases brought by vulnerable groups, a trend we are already seeing in Australia. In the last year, several cases were brought by First Nations people and Indigenous youth. These challenged coal mines and gas projects impacting their traditional lands, or fought for greater government action to prevent islands in the Torres Strait being overwhelmed by sea level rise.

As demands for climate justice increase, further growth and worldwide spread of climate litigation now seems a given. ![]()

Jacqueline Peel, Director, Melbourne Climate Futures, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Through the magnifying glass: how cutting-edge technology is helping scientists understand baby corals

Marine Gouezo, Southern Cross University and Christopher Doropoulos, CSIRONew photographic technology has allowed scientists to dive beneath the ocean’s surface and peer into the hidden world of baby corals, to learn how these tiny organisms survive and grow in their crucial first year of life.

In a study just published, researchers from Southern Cross University and CSIRO describe how advanced imaging techniques offer new ways to monitor baby corals.

Corals provide vital habitat for a large variety of marine life. So it’s useful to better understand how baby corals select and attach to reefs, establish themselves and grow into adult corals.

This knowledge is particularly important if we want to help reefs recover from devastating events such as mass bleaching and cyclones.

The Secret Life Of Corals

The life of a coral begins in an annual, synchronised spawning event. Coral colonies release millions of tiny eggs and sperm into the water at the same time. They all rise to the surface where the eggs are fertilised, developing into embryos and then later, into larvae.

Over days or weeks, the millions of larvae disperse with ocean currents. If things go according to nature’s plan, the larvae eventually fall through the water, attach to a reef and grow into adult corals. This process is known as coral “recruitment”.

In healthy coral reefs, this recruitment occurs naturally. But as coral reefs become more degraded – such as through coral bleaching brought on by climate change – fewer coral larvae are produced. This often means recruitment slows down or stops, and natural recovery weakens.

Scientists are working on ways to ensure coral larvae attach to and grow on reefs. This includes collecting coral spawn from the ocean, rearing embryos in floating nurseries and releasing larvae onto damaged reefs.

Coral larvae are less than one millimetre in size, so recruitment occurs on a tiny scale, invisible to the human eye. To better understand the process, researchers traditionally attach artificial plates to the reef. Once corals have established themselves, the plates are taken back to the lab to be inspected under a microscope.

This method can provide valuable insights, but it does not replicate the natural reef environment. That’s where our research comes in. Essentially, we brought the lab to the reef.

Capturing The Reef In Incredible 3D Detail

Our new study explores the development and application of an innovative imaging approach known as underwater “macrophotogrammetry”.

The technology combines macrophotography – photographing small objects close-up, at very high resolution – and photogrammetry – taking measurements from photos. In this case, we used photogrammetry to “stitch” photos together to recreate three-dimensional models, such as the one below.

The three round objects in the model are “targets” we placed to help the software stitch the photos together. Look closely, and you’ll see a nail head to the left of each target. To give you an idea of the scale of the model, the nail head is 2.8mm in diameter.

Reef-scale photogrammetry can be a valuable tool to track changes in coral cover and growth over time. However, it does not provide the detailed resolution needed to identify and observe tiny new corals.

Macrophotography provides this incredibly detailed scale. The coupling of the technologies also enables a comprehensive understanding of the entire ecosystem, from the smallest processes to the largest.

We conducted macrophotogrammetry surveys near Lizard Island on the Great Barrier Reef. We marked several 25cm x 25cm locations on the reef. We then captured hundreds of photographs taken at different angles using high-resolution cameras.

Photogrammetry software was used to process the photos, creating precise 3D models that represent the small sections of reef at very high resolution.

The models were examined to find where baby corals settle, to mark their location and measure their size. They reveal the complexity in the reef micro-structure, including tiny crevices, where coral larvae often settle.

The models also reveal diverse micro-organisms such as small turf algae or invertebrates, which interact with corals during the recruitment process.

Macrophotogrammetry surveys can be conducted at the same reef locations over time. This allows us to monitor the survival and growth of baby corals, and observe changes in the organisms living near them.

Looking Ahead

Complementary techniques may increase the potential of macrophotogrammetry even further. For example, coral larvae can be dyed various colours before release, making them more visible when they swim to and settle on the reef. This could be captured in 3D models to allow even better tracking of larval restoration efforts.

The use of macrophotogrammetry will deepen our understandings of why some larvae settle and survive on reefs, and others do not. This knowledge can help support our efforts to improve the overall conservation and recovery of coral reefs.

Its application need not be limited to coral reef ecosystems. We are excited about the potential of the technology to drive marine research more broadly.![]()

Marine Gouezo, Postdoctoral research fellow, Southern Cross University and Christopher Doropoulos, Senior research scientist, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You’ve heard the annoyingly catchy song – but did you know these incredible facts about baby sharks?

Jaelen Nicole Myers, James Cook University“Baby shark doo-doo doo-doo doo-doo, baby shark doo-doo doo-doo doo-doo …” If you’re the parent of a young child, you’re probably painfully familiar with this infectious song, which now has more than 13 billion views on YouTube.

The Baby Shark song, released in 2016, has got hordes of us singing along, but how much do you really know about baby sharks? Do you know how a baby shark is born, or how it survives to become an apex predator?

I study coastal marine ecology. I believe baby sharks are truly fascinating, and I hope greater public knowledge about these creatures will help protect them in the wild.

So sink your teeth into this Q&A on the weird and wonderful world of baby sharks.

How Are Baby Sharks Conceived And Born?

To the human eye, shark courtship practices may seem barbaric. Males typically attract the attention of a female by biting her. If successful, this is generally followed by even toothier bites to hold on during copulation. Females can carry the scars of these encounters long after the mating season is over.

The act of copulation itself is comparable to that of humans. The male inserts its sexual organ, known as a “clasper”, into the female and releases sperm to fertilise the eggs.

However, in extremely rare cases, sharks can reproduce asexually – in other words, embryos develop without being fertilised. This occurred at a Queensland aquarium in 2016, when a zebra shark gave birth to a litter of pups despite not having had the chance to mate in several years.

Sharks give birth in a variety of ways. Some species produce live pups, which swim away to fend for themselves as soon as they’re born. Others hatch from eggs outside the mother’s body. Remnants of these egg cases have been found washed up on beaches across the world.

How Big Is A Litter Of Shark Pups?

Litter size across sharks varies considerably. For example, the grey nurse shark starts with several embryos but only two are born. This is because the embryos actually eat each other while in utero! This leaves only one survivor in each of the mother’s two uteruses.

Intrauterine cannibalism may seem disturbing but is nature’s way of ensuring that the strongest pups get the best chance of survival.

In contrast, other species such as the whale shark use a completely different strategy to ensure some of their offspring survive: having hundreds of pups in a single litter.

Where Do Baby Sharks Live?

The open ocean is a dangerous place. That’s why pregnant female sharks often give birth in shallow coastal waters known as “nurseries”. There, baby sharks are better protected from harsh environmental conditions and roaming predators, including other sharks.

Sites for shark nurseries include river mouths, estuaries, mangrove forests and coral reef flats.

For example, the white shark has established nursery grounds along the east coast of Australia, where babies may remain for several years before moving to deeper waters.

Although most types of sharks are confined to saltwater, the bull shark can live in freshwater habitats. Bull shark pups born near river mouths and estuaries often migrate upstream (sometimes vast distances inland) to escape being preyed upon.

When Are Baby Sharks Born?

Sharks, like most animals in the wild, generally give birth during periods that provide favourable conditions for their offspring.

In Australia, for example, scalloped hammerheads and bull sharks tend to breed in the wet summer months when nursery grounds are warmer and there are rich feeding opportunities.

How Long Do Baby Sharks Take To Grow Up?

Sharks grow remarkably slowly compared to other fish and remain juveniles for a long time. Although some species mature in a few years, most take considerably longer.

Take the Greenland shark – the world’s longest living shark. It can live to at least 250 years and according to recent research, it’s thought to take more than a century to reach sexual maturity.

What Threats Do Baby Sharks Face?

While small, sharks must eat or be eaten – all the while enduring the elements and finding enough food to survive and grow.

Yet there is another challenge: humans. In fact, we are the greatest threat to sharks.

Shark nurseries are heavily concentrated in coastal zones, and often overlap with human activities such as fishing, boating and coastal development. And because sharks grow so slowly, they are particularly to vulnerable to overfishing because when populations decline, they can take a long time to bounce back.

Much More To Learn

Scientists are still working to understand the life cycles of the 500-plus species of sharks in our oceans. Each time I hear the song Baby Shark, it reminds me there’s a lot more work to do.

It’s crucial to keep monitoring and studying these baby wonders of the deep, to ensure shark populations survive and we maintain the delicate balance of our underwater ecosystems.![]()

Jaelen Nicole Myers, PhD Candidate, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Glide poles: the great Aussie invention helping flying possums cross the road

Next time you’re road-tripping along the east coast, keep an eye out for a little-known Aussie invention piercing the skyline: glide poles. For Australia’s gliding possums, or gliders, they’re the next best thing since tall trees.

These tall timber structures, with timber cross arms near the top, give gliders a way to cross big roads. They can shimmy up a pole on one side of the road and then leap to another (and another) to get to the other side.

After witnessing the earliest experiments with glide poles decades ago, it’s heartening to see the design refined and replicated up and down the east coast.

The world’s largest gliding marsupial, the greater glider, was listed nationally as endangered a year ago this month. That’s because their populations had declined by 80% in just 20 years. As land-clearing and bushfires continue to destroy old growth forests with tall trees and hollows, gliders need all the help they can get.

Biomimicry With Wooden Poles

From the match-box sized feathertail glider to the small cat-sized greater glider, Australia’s 11 species each have a gliding membrane, or patagium. This a thin area of skin stretching from the ankles to the wrists or hands.

When a glider leaps from a tree (or glide pole), it extends its front and hind limbs, stretching out its patagium, which allows it to glide.

In 1993 Ross Goldingay, one of Australia’s leading glider ecologists, came up with the idea of using tall wooden power poles (without wires) as road-crossing stepping-stones for gliders. The glide poles would act as substitutes for tall trees, so it was a very simple and elegant form of what’s known as “biomimicry”.

Ross directed the placement of glide poles on either side of a powerline easement at Bomaderry Creek near Nowra in southern New South Wales. The trial aimed to ensure yellow-bellied gliders could still cross the easement if it was developed into a local road.

Unfortunately, the Bomaderry Creek glide poles were never monitored. More than ten years later, a series of successful trials at Mackay and Compton Road in Brisbane demonstrated gliders would readily use glide poles. I recall showing Ross early images of squirrel gliders shimmying up the smooth, hardwood poles on the Compton Road land bridge soon after we installed cameras. We were blown away!

The poles needed to be tall enough to enable a comfortable glide crossing of the intervening gap. This is where trigonometry and the laws of physics come in, to get the calculations right for the species being targeted.

Since then, glide poles have become a fixture of upgrades along the Hume Highway in Victoria, the Pacific Highway in NSW and the Bruce Highway in Queensland.

Do The Poles Reconnect Glider Populations?

We are gradually gathering more evidence of glide pole use. Squirrel gliders, sugar gliders and feathertail gliders have been recorded using glide poles to cross roads at several locations.

Mahogany gliders, yellow-bellied gliders and southern greater gliders have also been recorded using glide poles.

Most notably, retrofitting a glider crossing into a road that previously presented a barrier to squirrel glider movement restored gene flow between populations on either side within five years.

Celebrating Some Of Australia’s Most Iconic Wildlife Crossings

Glide poles are one of many structures designed to provide safe road crossing opportunities for wildlife.

Pipes and box culverts can provide safe passage under the road, while land bridges and rope canopy bridges offer an alternative pathway over the road.

When combined with fencing, these structures reduce roadkill, provide access to resources on both sides of the road, and enable gene flow.

My new book combines an exploration of the how, when, where and why wildlife crossings evolved in eastern Australia with a travel guide to 57 of its most iconic sites.

The Road Ahead

We need to conserve, protect and restore our natural landscapes. This is especially the case in a rapidly changing climate. Our unique native species need to be able to move and adapt to the changing environment.

Carving up the landscape for road networks has been particularly bad for wildlife, with many populations becoming increasingly fragmented and increasingly isolated. But roads no longer need to act as roadblocks for the movement of many native species.

Engineers and ecologists have come together over recent years to find new ways to support the safe passage of animals from one side of the road to another. Their efforts deserve to be celebrated. Especially glide poles. They may not be as famous as the good old Hills Hoist clothesline, but they certainly deserve a gong as a great Australian invention. Certainly worth a nod when you pass by on your next great Aussie road trip.![]()

Brendan Taylor, Adjunct Research Fellow in the Faculty of Science & Engineering, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Keen to get off gas in your home, but struggling to make the switch? Research shows you’re not alone

Sangeetha Chandrashekeran, The University of Melbourne and Julia de Bruyn, The University of MelbourneMore than five million households in Australia are connected to the gas network. Tackling climate change requires homes and businesses to move away from gas, and instead embrace electric appliances as the power grid shifts to renewable energy.

People can save considerable money by switching away from gas – even more so if they have solar panels installed. But still, millions of Australians haven’t yet made the move. Why?

Our new research, released today, seeks to shed light on this question. We focused on lower-income households in Victoria and found while most participants supported the transition from gas, few owned electric appliances for heating, cooking and hot water.

There were two main barriers: people couldn’t afford the upfront cost of buying new electric appliances, or were renting and so had little or no say over what appliances were installed. Overcoming these and other challenges is crucial to ensure no-one gets left behind in Australia’s energy transition.

Making It Fair For All

Victoria has committed to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045. To help achieve this, the state government is developing a plan for the state to electrify. Other states and territories are also moving in this direction.

But to date, not enough research and policy attention has been paid to making this transition fair and equitable for everyone.

Low-income households spend a larger proportion of their income on energy bills compared to higher-income households. This is despite those households using less energy.

The affordability of gas will become worse as more households electrify. That’s because part of a gas bill includes the fixed cost of running gas infrastructure – so as progressively fewer people use gas, the remaining users pay more.

And those who don’t make the move away from gas miss out on the long-term economic benefits. Analysis last year suggested a typical Victorian household could reduce its annual energy costs by A$1,020 by replacing gas heating, cooking and hot water systems with electric ones. The figure rises to $1,250 for those with solar power. These savings will be amplified if the price of gas continues to rise relative to electricity.

That’s why it’s important to help as many lower-income people as possible to make the switch to electric appliances. Our research set out to understand what might prevent or enable that shift.

We studied households in Victoria: the state with the highest prevalence of residential gas use in Australia and where plans for an economy-wide transition away from fossil gas are underway.

What We Found

We conducted an online survey, which received 220 eligible responses. We also undertook focus groups with 34 people. All participants were from lower-income households.

Most participants – 88% – used gas in the home, reflecting its prevalence in Victoria.

More than two-thirds indicated some level of support for a transition away from household gas to cleaner energy sources. Support was greater with higher levels of education. There was no significant difference based on financial stress, housing tenure, location or age.

But this support had not translated into action. Just one in ten surveyed households had replaced gas appliances with electric ones within the past five years. Among those who had switched or planned to switch, the main reasons were lower running costs and environmental benefits.

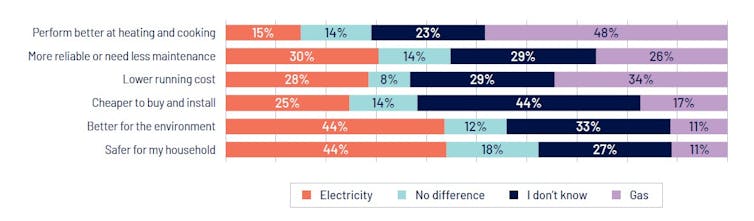

Respondents considered electric appliances to be safer and better for the environment. Gas appliances were considered better for heating and cooking. Many respondents were unsure about the relative benefits of electric versus gas appliances when it came to cost, reliability, safety and the environment.

Preferences were strongly linked to what people were currently using. Most people preferred gas cooktops over electric ones, because of the perceived speed, ease and flexibility. However, few participants had used electric induction stoves, which can also offer these benefits.

People who spoke a language other than English were significantly more likely to prefer gas for heating and hot water.

For those who had not replaced gas appliances, being a renter was one of the biggest barriers to electrification. Some renters said they lived in poor housing, but were unwilling to request improvements in case the landlord increased the rent or evicted them.

Respondents also said they would struggle to afford the upfront costs of electrification, such as buying new appliances and, in some cases, wiring upgrades and other building modifications.

Many participants were aware of and had received state government assistance to help with energy bills. But far fewer people knew about or had used programs that could support them to adopt electric appliances.

Embracing The Switch

An overall strategy is needed to help all households make the shift to electric appliances and technology. Our research suggests this must include specific measures for lower-income households, such as:

targeted and well-promoted electrification programs

more evidence-based information on the benefits of electric appliances

incentives for landlords and standards requiring efficient electric appliances in rental homes

means-tested rebates for electric appliances such as reverse cycle air-conditioners and heat pump hot water, and where appropriate, no- or low-interest loans.

These measures should, where possible, be linked to measures to improve household energy efficiency. And lower-income households, as well as others facing barriers to getting off gas, must be included when planning the transition.

Researchers David Bryant and Damian Sullivan from the Brotherhood of St Laurence contributed to this article and co-authored the research upon which it is based.![]()

Sangeetha Chandrashekeran, Senior Research Fellow, Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course, The University of Melbourne and Julia de Bruyn, Associate Investigator, ARC Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Could the law of the sea be used to protect small island states from climate change?

Climate change will wreak havoc on small island developing states in the Pacific and elsewhere. Some will be swamped by rising seas. These communities also face more extreme weather, increasingly acidic oceans, coral bleaching and harm to fisheries. Food supplies, human health and livelihoods are at risk. And it’s clear other countries burning fossil fuels are largely to blame.

Yet island states are resourceful. They are not only adapting to change but also seeking legal advice. The international community has certain legal obligations under the law of the sea. These are rules and customs that divvy up the oceans into maritime zones, while recognising certain freedoms and duties.

So island states are asking whether obligations to address climate change might be contained in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. This is particularly important as marine issues have not received the attention they deserve within international climate negotiations.

If states do have specific obligations to stop greenhouse gas pollution damaging the marine environment, then legal consequences for breaching these obligations could follow. It is possible small island states could one day be compensated for the damage done.

Why Seek An Advisory Opinion?

The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea is an independent judicial body established by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. The tribunal has jurisdiction over any dispute concerning the interpretation or application of the convention and certain legal questions requested of it. The answers to these questions are known as advisory opinions.

Advisory opinions are not legally binding, they are authoritative statements on legal matters. They provide guidance to states and international organisations about the implementation of international law.

The tribunal has delivered two advisory opinions in the past: on deep seabed mining and illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing activities. These proceedings attracted submissions from states, international organisations and non-governmental organisations such as the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

Late last year, the newly established Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law submitted a request for advice to the tribunal. It concerns the obligations of states to address climate change, including impacts on the marine environment.

The tribunal received more than 50 written submissions from states and organisations offering opinions on how it should respond. These submissions, from Australia and New Zealand among others, were recently made public.

While the convention was not designed as a mechanism for regulating climate change, its mandate is broad enough to consider the connection between climate and the oceans. To establish this, the 40-year-old framework agreement must be interpreted in light of changing global circumstances and changing laws, including obligations to strengthen resilience in the high seas. One avenue to achieve this is through an advisory opinion from the tribunal.

The Question Before The Tribunal

The question to the tribunal asks, what are the specific obligations of states:

(a) to prevent, reduce and control pollution of the marine environment in relation to the deleterious effects that result or are likely to result from climate change, including through ocean warming and sea level rise, and ocean acidification, which are caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere?

(b) to protect and preserve the marine environment in relation to climate change impacts, including ocean warming and sea level rise, and ocean acidification?

This question invokes specific language from the convention. That provides clues as to which sections of the treaty the tribunal will refer to in its opinion.

The question refers explicitly to the part of the convention entitled “Protection and Preservation of the Marine Environment”. This part sets out the general obligation of states to protect and preserve the marine environment, as well as measures to “prevent, reduce and control pollution”. It also tells states they must not transfer damage or hazards, or transform one type of pollution into another.

Pollution of the marine environment is defined in the convention as:

the introduction by man, directly or indirectly, of substances or energy into the marine environment, including estuaries, which results or is likely to result in such deleterious effects as harm to living resources and marine life, hazards to human health, hindrance to marine activities, including fishing and other legitimate uses of the sea, impairment of quality for use of sea water and reduction of amenities.

What If States Do Not Meet Their Obligations?

The tribunal will need to answer a key question for the law of the sea: can the convention be understood as referring to the drivers and effects of climate change? And if so, in what ways does the convention require that they be addressed by states?

What the commission’s question does not ask is, what happens when states do not meet their obligations? The answer is particularly important to small island states, who are dissatisfied with ongoing negotiations on addressing loss and damage associated with climate change impacts.

Obligations relating to climate change are contained within other treaties and rules, including the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement. Small island states have sought advice from different courts to clarify these obligations.

The International Court of Justice will consider a wider set of legal issues on climate obligations next year.

The fact that the court has authorised the commission to participate in this separate advisory opinion request signals the UN’s main judicial body will take account of the tribunal’s opinion. It’s also worth noting the tribunal is likely to deliver its views on the law of the sea first, setting the stage for a broader interpretation of international law when it comes to taking responsibility for polluting the atmosphere.

Sustained pressure from small island states is advancing our understanding of the obligations of states to address climate change.![]()

Ellycia Harrould-Kolieb, Lecturer and Research Fellow in Ocean Governance, University of Melbourne and Postdoctoral Researcher, UEF Law School, University of Eastern Finland, The University of Melbourne and Margaret Young, Professor, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

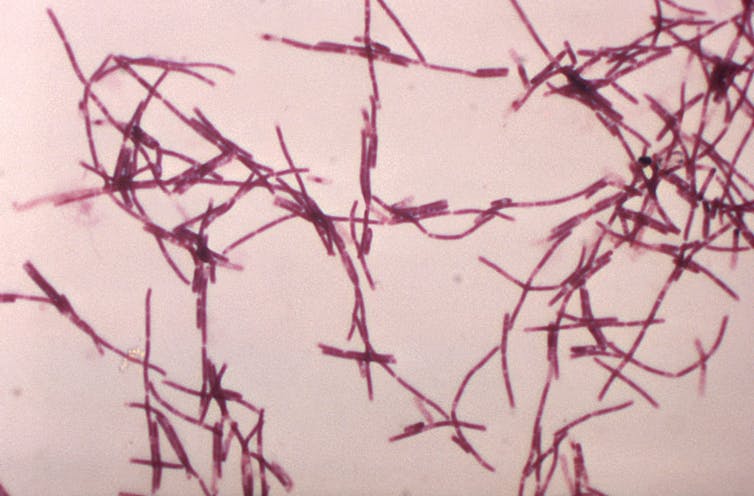

The feral flying under the radar: why we need to rethink European honeybees

Amy-Marie Gilpin, Western Sydney University; James B. Dorey, Flinders University; Katja Hogendoorn, University of Adelaide, and Kit Prendergast, Curtin UniversityAustralia’s national parks, botanic gardens, wild places and green spaces are swarming with an invasive pest that is largely flying under the radar. This is yet another form of livestock, escaped from captivity and left to roam free.

Contrary to popular opinion, in Australia, feral colonies of the invasive European honeybee (Apis mellifera) are not “wild”, threatened with extinction or “good” for the Australian environment. The truth is feral honeybees compete with native animals for food and habitat, disrupt native pollination systems and pose a serious biosecurity threat to our honey and pollination industries.

As ecologists working across Australia, we are acutely aware of the damage being done by invasive species. There is rarely a simple, single solution. But we need to move feral bees out of the “too hard” basket.

The arrival and spread of the parasitic Varroa mite in New South Wales threatens to decimate honeybee colonies. So now is the time to rethink our relationship with the beloved European honeybee and target the ferals.

What Makes A Hive Feral?

European honeybees turn feral when a managed hive produces a “swarm”. This is a mass of bees that leaves the hive seeking a new nest. The swarm ultimately settles, either in a natural hollow or artificial structure such as a nesting box.

With up to 150 hives per square kilometre, Australia has among the highest feral honey bee densities in the world. In NSW, feral honeybees are listed as a “key threatening process”, but they lack such recognition elsewhere.

Feral honeybees have successfully invaded most land-based ecosystems across Australia, including woodlands, rainforests, mangrove-salt marsh, alpine and arid ecosystems.

They can efficiently harvest large volumes of nectar and pollen from native plants that would otherwise provide food for native animals, including birds, mammals and flower-visiting insects such as native bees. Their foraging activities alter seed production and reduce the genetic diversity of native plants while also pollinating weeds.

Unfortunately, feral honeybees are now the most common visitors to many native flowering plants.

Are Feral Bees Useful In Agriculture?

Feral honeybees can pollinate crops. But they compete with managed hives for nectar and pollen. They can also be an reservoir of honeybee pests and diseases such as the Varroa mite, which ultimately threaten crop production. That’s because many farms rely on honeybees from commercial hives to pollinate their crops.

So reducing feral honeybee density would benefit both honey production and the crop pollination industry, which is worth A$14 billion annually.

Improved management of feral honeybees would not only help to limit the biosecurity threat, but increase the availability of pollen and nectar for managed hives. It would also increase demand for managed honeybee pollination services for pollinator dependent crops.

What Are Our Current Options?

Tackling this issue will not be straightforward, due to the sheer extent of feral colony infestation and limited tools at the disposal of land managers.

If the current parasitic Varroa mite infestation in NSW spins out of control, it may reduce the number of feral hives, with benefits for the environment. Fewer feral hives would be good for the honey industry too.

Targeted strategies to remove feral colonies on a small scale do exist and are being applied in the Varroa mite emergency response. This includes the deployment of poison (fipronil) bait stations in areas exposed to the mite.

While this method seems to be effective, the extreme toxicity of fipronil to honeybees limits its use to areas that do not contain managed hives. In addition, the possible effects on non-target, native animals that feed on the bait, or poisoned hive remains, is still unstudied and requires careful investigation.

Where feral hives can be accessed, they can be physically removed. But in many ecosystems feral colonies are high up in trees, in difficult to access terrain. That, and their overwhelming numbers, makes removal impractical.

Another problem with hive removal is rapid recolonisation by uncontrolled swarming from managed hives and feral hives at the edges of the extermination area.

Taken together, there are currently no realistic options for the targeted large-scale removal of feral colonies across Australia’s vast natural ecosystems.

Where To Now?

For too long, feral honeybees have had free reign over Australia’s natural environment. Given the substantial and known threats they pose to natural systems and industry, the time has come to develop effective and practical control measures.

Not only do we need to improve current strategies, we desperately need to develop new ones.

One promising example is the use of traps to catch bee swarms, and such work is underway in Victoria’s Macedon Ranges. However, this might be prohibitively expensive at larger scales.

Existing strategies for other animals may be a good starting place. For example, the practice of using pheromones to capture cane toad tadpoles might be applied to drones (male bees) and swarms. Once strategies are developed we can model a combination of approaches to uncover the best one for each case.

Developing sustainable control measures should be a priority right now and should result in a win-win for industry, biosecurity and native ecosystems.

If there is something to learn from the latest Varroa incursion, it is that we cannot ignore the risks feral honeybees pose any longer. We don’t know how to control them in Australia yet, but it is for lack of trying.