Palm Beach Pavilion to be renamed the Lieutenant Colonel Douglas Marks DSO, MC Pavilion

Ocean facing side of Palm Beach Surf Pavilion in January 2019

On that day, 100 years ago, the young soldier aged just 24, while picnicking at Palm Beach, drowned in heavy surf trying to rescue a swimmer caught in a rip. His death and the death of the woman he dived into save, was instrumental in the formation of the Palm Beach SLSC.

Although her body was later recovered, his was never found.

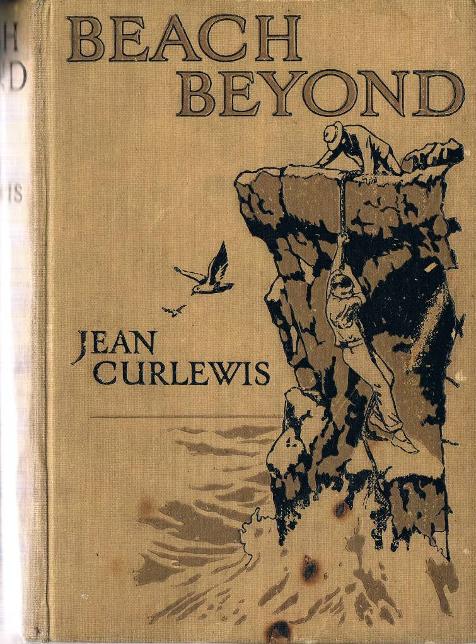

Newspaper reports carried the tragedy to their readers far and wide, some even reporting the rescuers had to run over the hill to the store at Gow's wharf to telephone for help, there being no Ocean road yet at Palm Beach, the only access, and telephone, was over the Palm Beach road. Jean Curlewis, sister of Adrian Curlewis, in her book 'Beach Beyond', a fiction work based on early days at Palm Beach, speaks about this tragedy. Her brother was on the sand that day, as was good friend, 'Jack' Ralston.

At Black Rock, close to the Palm Beach Pavilion, an information board installed by Pittwater Council, once informed visitors of this man's heroism:

Adrian's daughter Philippa, while speaking about what would run in her account shared here years ago, The Breakers at Beach Beyond 1901 – 2011, spoke about her father being on the beach that day and being witness to the drowning. The incident sparked him, Jack Ralston and other local full-time Palm Beach residents, after a meeting by called by the organisation then known as the Palm Beach Progress association, and the drowning of another in March of the same year, to hire a life saver for the coming 'season', finding Austin Dellit - a foundation member of 'The Wombats' camp at Collaroy, from which the Collaroy SLSC would be formed in 1911, and soon after form the Palm Beach SLSC.

SURF LIFE-SAVING ASSOCIATION.

At an executive meeting of this association on Monday a good deal of business was put through. Palm Beach Progressive Association notified that they had decided to set up a complete life saving outfit, and will have an expert life saver on the beach. Assistance was asked for from the association, and it was decided to meet them in the matter. The secretary of the S.L.S.A. will confer with the Palm Beach body. ON THE BEACHES (1921, February 18). Arrow (Sydney, NSW : 1916 - 1933), p. 12. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103430118

Next Summer the North Steyne club visited to provide a demonstration and instruction in current life saving techniques at the season's opening. The Surf Life Saving Association, striving to have beaches in the then Warringah Shire protected, provided and promoted such demonstrations on beaches that were without any form of a Surf Life Saving Club.

Shortly after the visit Len Palmer, a member of the Manly Club and frequent visitor to Palm Beach, discussed with the young men who would camp in the Reserve at the south end of the beach that they could support the new lifeguard as volunteers and form their own volunteer surf life saving club. A subsequent meeting at E.P.M. Sheedy's Palm Beach home on November 26th 1921, attended by permanent residents and summer permanents, proposed, and seconded by Arthur Goddard, the formation of a group of volunteer lifesavers and a Club to be named the 'Palm Beach Surf Life Saving Club'.

Those present at this meeting are the stuff of Pittwater legends and pioneer families; C. Larsen, Walter Rayner, J. Gonslaves, Arthur Goddard, L. Gallagher, Len Palmer, Roy Ellis, H.A. Wilshire, A. Milton, Geoffrey Oatley, Keith Oatley and Austin Dellit. Adrian Curlewis, who had witnessed the drowning the year before and was determined to see change, was a member of the Committee from its outset.

Influential and prominent members of Sydney society and Palm Beach permanent residents at this time were invited and accepted Vice-Presidency of this new club; A.J. Hordern, Thomas Peters, W.Goddard, Dr H.H. Bullmore, Judge Clive Curlweis, William Chorley, W.J. Barnes and R.B. Orchard.

The club badge, which no member could wear on his costume until he had passed his Bronze Medallion, featured a Cabbage Tree Palm on a circular backdrop. The Club's green and black colours stem from those of the First Battalion, AIF and were proposed by Great War veteran J.F. Mant.

Members trained hard this first season with 23 weekenders and permanent residents gaining their Bronze Medallion. They improvised for equipment; their first reel, secured permanently on the beach, homemade, with a ferry cork belt was supplemented in the southern corner a box line fixed to a post had to suffice.

On January 1st, 1923, they hosted their first carnival:

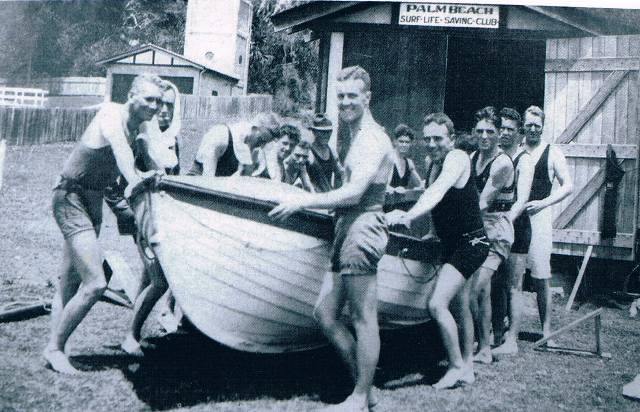

This R&R squad competed in the first Surf Carnival to be held at Palm Beach on 1/1/1923. Adrian Curlewis can be seen at back on left side - photo courtesy Philippa Poole (nee Curlewis)

PALM BEACH CARNIVAL.

The attendance of 800 persons at Palm Beach carnival on New Year's Day was a record. It was Palm Beach's first attempt at carnival management, and the new body must be complimented upon the excellence of the programme.

Don Mclntyre, who forsook the Cronulla fixture at the last minute in order to help Palm Beach, was ably seconded by Messrs. J. Lee (Collaroy), J. Cole (Newport), J. Evans (Collaroy), and Bert Vesper (Newcastle). Len Palmer, Austin Delitt, and Mr, Peters (an enthusiastic local resident) were responsible for a great afternoon's entertainment. Newport, Mona Vale, Palm Beach and North Narrabeen paraded in their new uniforms, making a great show. There were 120 competitors.

ALARM REEL RACE.— North Narrabeen, 1.

SURF RELAY RACE.— North Narrabeen, 1 : Palm Beach, 2 ; Collaroy, 3. Palm Beach led at the second relay, and a great race ensued between G. Oatley (Palm Beach) and C. Proud foot (North Kurrabeen). Proudfoot snared a wave and won. Cronulla & Palm Beach Carnivals (1923, January 5). Arrow (Sydney, NSW : 1916 - 1933), p. 7. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103540446

The first Club House, a shed, was built beside the Peter's residence on land still owned, at that time, by the Barrenjoey Land Company. This too was made by members and afforded them a place to change and a place to stow club equipment. It was built to store the club's first surf boat.

The First Shed: Left; Merle Loxton, Laurie Gallagher, Tim Gonsalves and Sydney Gonsalves. H.R. Ayres and Midge Gonsalves. Right; Adrian Curlewis, Len Palmer, M Ormsby.

Unfortunately the first surf boats were too heavy to be carried too far (they required 12 men to lift and move them) while the southern end of the Palm Beach, with its natural run out, was the best place to launch this craft from. It seemed sensible to leave the boat in the southern corner.

PALM BEACH AWAKE. Palm Beach awoke from its Winter slumber last Sunday, and held its second annual meeting. The following officers were elected : Patron, W. J. Barnes ;president, A. J. Hordern ; vice presidents, J. Goldsmith, T. Peters, D. B. Wilshire and E. R. Moser; committee, J. Ralston, M. Loxton, A. Goddard, S. Gonsalves, L. Gallagher; captain, Adrian Curlewis ; boat captain, A. Goddard ;vice-captain, N. Holt ; hon. secretary, L. A. Palmer ; hon. treasurer, N. H. Erwin. R. D. Doyle, hon. Examiner in chief S.L.S.A.A., was the guest of theclub over the week-end. He made a fine speech at the annual meeting, and later instructed the members on the new R. and R. methods. The club is in a flourishing state. The annual carnival will be held on New Year's Day. Palm Beach will entertain all competitors at luncheon. A fine band has been engaged, and entry to all events is to be free. Mr. T. Peters has presented the club with a 600gal. tank, two showers, a pump, and sufficient guttering and downpipe for the completion of the clubroom. WHAT'S DOING ON THE SURF BEACHES. (1923, December 7). Arrow (Sydney, NSW : 1916 - 1933), p. 13. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103537126

PALM BEACH AWAKE. Palm Beach awoke from its Winter slumber last Sunday, and held its second annual meeting. The following officers were elected : Patron, W. J. Barnes ;president, A. J. Hordern ; vice presidents, J. Goldsmith, T. Peters, D. B. Wilshire and E. R. Moser; committee, J. Ralston, M. Loxton, A. Goddard, S. Gonsalves, L. Gallagher; captain, Adrian Curlewis ; boat captain, A. Goddard ;vice-captain, N. Holt ; hon. secretary, L. A. Palmer ; hon. treasurer, N. H. Erwin. R. D. Doyle, hon. Examiner in chief S.L.S.A.A., was the guest of theclub over the week-end. He made a fine speech at the annual meeting, and later instructed the members on the new R. and R. methods. The club is in a flourishing state. The annual carnival will be held on New Year's Day. Palm Beach will entertain all competitors at luncheon. A fine band has been engaged, and entry to all events is to be free. Mr. T. Peters has presented the club with a 600gal. tank, two showers, a pump, and sufficient guttering and downpipe for the completion of the clubroom. WHAT'S DOING ON THE SURF BEACHES. (1923, December 7). Arrow (Sydney, NSW : 1916 - 1933), p. 13. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103537126 Warringah Council were approached with a request to build a second 'shed' for the boat on council land at the southern end. In the 1922-23 season, permission granted, the original shed was moved to Hordern Reserve and Dellit, reengaged for his second season, with these original members, carried out extensions and alterations. It was still a shed when completed but now had a verandah. In 1925 a shower room and fence around the clubhouse were added.

Right: The second shed in Hordern Park.

Club members were increasing rapidly too, much of this due to Adrian Curlewis' championing of the club and Palm Beach itself to fellow students at the University of Sydney's Law School and its residential colleges. Visitors and residents were kept safe, some rescued during these first seasons.

Palm Beach was still a fair way from the rest of Sydney then though and after these first seasons, and the proven necessity for full-time lifeguards during Summer, supported by squads of volunteers, membership fell away and Dellit, after four seasons as Palm Beach's Lifeguard, and Instructor for new members, did not take up a fith season. Three years, and three different lifesavers later, Captian of the Club, Adrian Curlewis, in examining the problem, knew the Club and Palm Beach residents had to provide better accommodation for the full-time lifeguard then that already in place in the ramshackle shed. He approached Warringah Council to build further extensions which would provide a modicum of privacy for the resident lifesaver during the season.

A.J. Hordern, whose Summer residence was beside the Reserve named after him, had, according to some residents, a growing dislike of this modified second 'ramshackle' shed, especially the way it interfered with the view from his balcony and the noise that came from it. He offered to finance the building of a new clubhouse as long as it was on a site other then where it was at present. He would then 'lend' one hundred pounds on improving this park.

The humble sheds, and all they represented in donated materials and members labour, were finished by December 1929 when, after years of squabbling between club members and manipulators within the community and Warringah Shire Council itself, a new clubhouse, further up the beach was opened.

A little from those pages of the past about this Mr. Marks' service as an ANZAC and that tragic incident:

BEACH TRAGEDY.

A LOST HERO.

GIRL ALSO DROWNED.

MAGNIFICENT RESCUE ATTEMPTS

SYDNEY, Sunday.

An epic tragedy, in which the sadness of death was brightened by cool unflinching heroism, was enacted at Palm Beach, a seaside resort near Broken Bay, this afternoon, when Johanna Rogers, 33 years of age, of Leichhardt, and Lieut.-Colonel Marks lost their lives in the surf.

The picnics party arrived, at the beach, which is far removed from habitation, about mid-day, and shortly afterwards, several of them went into the surf. Johanna Rogers got into difficulties and was carried out to sea.

It was some minutes before her plight was noticed, when two members of the party unhesitatingly plunged in and attempted to swim out to her. But the distance was too great, and the would-be rescuers were compelled, by a common-sense regard for their own lives and recognition of the uselessness of trying to go further without life-lines, to return to the beach, where they fell down helplessly exhausted.

Then a life-line was improvised out of tent ropes and the like, and with this fastened to him, Lieut.-Colonel Marks went out into the breakers. He passed the three lines of surging waves successfully, and was well out into the rolling water beyond, when the line broke. Thereafter the gallant soldier was seen no more.

Other members of the party, undeterred by this tragic event, made repeated efforts to reach the two, fighting for life against current and waves, and eventually a man named Ralston, after a tremendous fight with the pounding waves, reached the girl.

Already very weak from his long and exceptionally hard swim, Ralston seized the still body and doggedly turned back towards the beach.

Then began a battle for life such as has never been seen before on the Australian Pacific coast. Time after time his companions on shore, some already worn out by their efforts, praying for his success, saw him go under; time after time he struggled to the surface again and forged desperately on towards the shore and safety. Fierce waves rolled him over, tossed him about, played with him and the girl which they had claimed as victim, like corks, but he plunged on and on. After what seemed an age to the agonised watchers on the shore, he got into the breakers and was swiftly carried into shallow water. Willing hands pulled him and the girl on to the dry sand, and feverishly set about trying to restore animation in the still body of the girl.

But their efforts were in vain. She was dead.

Ralston soon recovered from his ordeal, and with several others of the party who narrowly escaped drowning themselves, accompanied the saddened party to the nearest habitation, whence the police were communicated with.

There has been no further news of Lieut. Colonel Marks. BEACH TRAGEDY. (1920, January 30). The Urana Independent and Clear Hills Standard (NSW : 1913 - 1921), p. 6. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article116182266

PALM BEACH DROWNING

Colonel Marks' Bravery Evidence at Inquest

The circumstances surrounding the fatality at Palm Beach on January 25 were recalled this morning at an inquiry by the City Coroner (Mr. Jamieson) into the deaths of Miss Johanna Mary Rogers and Lieutenant-Colonel Douglas Marks. The latter lost his life in an attempt to save Miss Rogers, who had been carried out by the surf. His body has not yet been recovered.

Dr. S. N. Bray said he was bathing at Palm Beach when the life-savers brought in Miss Rogers' body. Witness tried unsuccessfully for an hour to restore animation.

Herbert Leslie McDonald, an accountant, living at Moruben-road, Mosman, stated that Colonel Marks was his brother-in-law. He was 24 years of age, and was a company manager. Marks was fair swimmer and had been decorated with the D.S.O., M.C., and Order of the White Eagle of Serbia. He arrived home from the war in December 1918, and was unmarried.

Story of Tragedy

"I was with him at Palm Beach on January 25," continued witness. "About 3 p.m. I heard a commotion, and, looking round, saw a woman a long way out in the surf, and two men holding her up. I ran towards the beach. Looking to the sea, I noticed that the men had had to leave the woman, and were coming back.

"Going along the beach, I saw my brother-in-law with a piece of clothes line, with a knot in it, wound round his waist. He was about to go out to the woman, and was accompanied by Messrs. Bromly and Hendry. After they had gone about twenty-five yards the three got into difficulties.

"The current was strong. Bromly called out a warning to the other two. Hendry evidently heard him, and made back for the shore; but Marks went on about another ten yards. He then threw up his hands. Hendry and Bromly had to be assisted out.

Where was the Life Line?

"I rushed in with my clothes on to go to Marks. The proper life-line could not be found. The crowd was holding on the line round Marks. There was a lot of excitement. I got more than half-way to Marks, when I was compelled to re-turn as I was hopeless trying to reach him. By the time I had turned to come in he had disappeared. It was not the usual bathing place."

Edward James Rogers, a butcher, of Leichhardt, said that Miss Rogers was his sister. She could swim, and had been in the habit of going surf bathing.

Horace James Hendry, an accountant, residing at Chatswood, said that he got within 20 yards of Marks when he lost sight of him. "Marks," added witness, "had on sand-shoes, trousers, and shirt, and was sucked down."

Holland Hodgson Wright, a wool appraiser, of Cremorne, stated that he recovered the woman's body. Witness, who is a member of the Cronulla Life Saving Club, said the whole of Palm Beach was dangerous to strangers who did not know it.

The Coroner's Remarks In recording a verdict of accidental death by drowning in each instance, the Coroner said "I feel sure that every-body concerned did their utmost to rescue this unfortunate woman. Unfortunately one of the bravest, Lieutenant-Colonel Marks, lost his life.

"It seems particularly sad that one who performed such glorious deed at the war and came through safely should have lost his life in this manner, but though it is sad in one way in another it appears to be a not unworthy end to a glorious career."

The Coroner also remarked that something should be done to warn visitors of the dangers existing at the beach.

PALM BEACH DROWNING (1920, February 25). Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 - 1931), p. 5. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article115869886

Mr. Douglas and Miss Rogers were not the only one around this time to lose their lives at this popular beach:

DROWNED AT PALM BEACH

BODY IN THE BREAKERS

A tutor, Walter A. Corry, of Whitton, was found drowned In the surf at Palm Beach late on Tuesday afternoon. He arrived in Sydney recently, and was staying with his sister. Mrs. Budge, in Holdsworth-street.Woollahra, He was a tutor at Mr. J. J. Taylor's station, Whitton, for some years. When the body was recovered the name was unknown, but Identification was established late yesterday by 'Mr. Andrew Sherard, of Whitton, in Sydney, on his way home from Victoria.

The body had not long been in the water when It was recovered. Mr. Meggitt, a resident, was walking along the beach when he saw the body in the breakers. Constable Grant, Mona Vale, was informed, and later he secured it. There was a gash on the forehead which had evidently been caused through contact with rocks. DROWNED AT PALM BEACH (1920, March 11). The Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article221380215

Douglas Gray Marks was born on March 20th, 1895 at Junee, New South Wales, the youngest son of Montague Marks, storekeeper, and his wife Elizabeth Caroline, née Plunkett.

Douglas Gray Marks was born on March 20th, 1895 at Junee, New South Wales, the youngest son of Montague Marks, storekeeper, and his wife Elizabeth Caroline, née Plunkett.

His father was a JP, sitting on the local Police Court from at least 1878.

The family moved to Neutral Bay, Sydney and Douglas attended Fort Street Boys' High School, Sydney, becoming a bank clerk, and studied mining engineering part time at Sydney Technical College.

In June 1914 Marks was commissioned second lieutenant in the 29th Infantry (Australian Rifles). He joined the Australian Imperial Force on November 20th and was appointed a second lieutenant in the 13th Battalion which sailed for Egypt in December. After landing at Gallipoli his battalion moved to Quinn's Post and Pope's Hill with the task of clearing Russell's Top. In its first week of action the 'Fighting Thirteenth' suffered very heavy casualties.

On May 2nd to 3rd, in the attack on Baby 700, the battalion temporarily captured the Chess Board and Dead Man's Ridge. Marks's personal knowledge of the enemy dispositions assisted his commanding officer Lieutenant-Colonel Burnage significantly. Having been acting adjutant, on 20 July he was promoted temporary captain but on August 7th he was wounded in the left foot and evacuated.

For outstanding service on Gallipoli he was awarded the Serbian Order of the White Eagle.

Order of the White Eagle of Servia

MAJOR DOUGLAS G. MARKS, Who has been awarded the Order of the White Eagle of Servia, the cable advice of which also notified his promotion to the rank of Major. Major Marks obtained a commission in the Australian Rifles just prior to the outbreak of war. He left Australia with the 13th Battalion as Second-Lieutenant, was in the original landing, and served right through the Gallipoli campaign. While on the peninsula he was successively promoted First-Lieutenant, Captain, and Adjutant. Since the evacuation, Major Marks has been with his battalion on the Western front. He is the youngest son of Mr. and Mrs. Montague Marks, of Sundridge, Lindsay-street, Neutral Bay. Order of the White Eagle of Servia (1916, December 31). Sunday Times (Sydney, NSW : 1895 - 1930), p. 9. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article121350082

A more detailed article about Douglas Marks' service:

LAST SACRIFICE OF GALLANT SOLDIER

Lt.-Col. D. G. Marks, of Whom Australia is Proud, Gives His Life for a Woman

Perhaps the grandest act of the brilliant life of Lieut.-Colonel. D. G. Marks, M.C., D.S.O., White Eagle of Servia, &c., one of the boys who took part in the Landing of the Australians at Gallipoli, and who covered himself with credit in succeeding operations in the course of the great war, was the act that cost him his life. In the effort to save a woman in difficulties in the surf at Palm Beach last Sunday he was drowned.

Previous attempts by stronger swimmers to rescue the woman had failed, and Colonel Marks, well knowing his limitations in the water, took the small chance of the forlorn hope, and went over the top — for the last time. One of the true comrades of the A.I.F. who, as a subaltern, shared the difficulties of the soldiers, and whose first thought was for his men, and not for himself, he endeared himself to the Anzacs. His watchword was Service. The youngest man to attain to the high rank he held in the Army, he was ever faithful to his battalion. He had the complete confidence of his fellow officers and the men of his command, and more than one successful operation of those under him was attributed to the determination of the men not to fail a commander whose faith in them, and care for them, were unbounded.

A Most Promising Soldier

In the untimely death of this young officer Australia has lost one of her most promising soldiers — one who would have helped to maintain that spirit of the volunteer and military enthusiasm which is to mean so much in the future defence of this country. Colonel Marks was no mere product of this war — the fields of Gallipoli and France — but showed that the foundations of his peace training were well and truly laid. The distinctions he won on the field proved that he could carry his ideas and ideals of soldiering with success through the test of war.

Like others of our leaders, he believed in preparing for war in peace, and had he, like them, started in this war with more mature years, there is little doubt that he would have held a very high position in the Australian Forces. Colonel Marks began his military career as a cadet officer in the 26th Battalion Senior Cadets, and from the start he displayed that thoroughness of organisation and energy of execution that marked all his work in the A.I.F. Later he obtained a commission as 2nd Lieutenant in the Australian Rifles, with which he was serving at the outbreak of war. He was mobilised with the regiment for duty on Coast Defence during the first month of hostilities.

On September 14, 1914, he enlisted with the A.I.F. and went into camp at Kensington.

On November 20 he was gazetted as 2nd lieutenant, and posted to the 13th Battalion as the junior subaltern, joining the Battalion just before the embarkation for Egypt. In Egypt he set to work to ensure that his platoon was second to none, and toiled unceasingly to this end. If at first the men resented working harder than their comrades in the other platoons, they quickly caught the spirit of their commander, and were all keen to follow his example.

LT.-COL. D. G. MARKS.

On the Peninsula

The memorable 25th of April found the 13th Battalion heavily engaged in the vicinity of Pope's Hill, with young Marks in command of one of the leading platoons. Here he quickly showed that he could put his theory and training into practice. At one time he found him-self in command of a body of men from nearly every unit on Anzac. These he re-organised, and with them he was successful in maintaining his part of the line. He was present throughout the whole operations on the Peninsula, with the single exception of eleven days, during which time he was evacuated, suffering from a wound in the foot.

He was promoted to lieutenant on May 25, 1915, and on June 4 he was appointed adjutant of his battalion, which position he held till the evacuation. He was later promoted to the rank of captain. As early as October of the same year he temporarily held command of the battalion. The great confidence that his senior officers had in him is shown by the fact that they entrusted the command of the battalion to so junior a captain, while senior officers were to be found in other battalions.

Even at this early stage of the war, his conduct and military skill had brought him to the notice of the higher commands. On arrival in France, the 13th Battalion had a short spell in the comparatively quiet sector round Bois Grenier before being transferred to the Somme.

At Pozieres Captain Marks again distinguished himself by his complete and thorough organisation of everything appertaining to the comfort and fighting efficiency of the battalion. During the fighting of November, 1916, he was promoted to the rank of major. At Bulle-court he was severely wounded by a fragment of shell that passed through his chest. For some time it was not expected that he would live; but careful treatment and a determined spirit brought him through.

A Battalion Command

While convalescent in England, Major Marks was appointed commandant of the depot at Verre Citidal, where about 2000 Australians were under treatment. Re- turning to France in August, though then only 21, he took over command of the battalion from (then) Major Murray, V.C. From then to almost the close, with the exception of two months, he commanded the battalion continuously throughout the strenuous operations in front of Ypres, during the trying days of early 1918, and in the last great advance to the Hindenburg line.

In the German attempt to break through to Amiens the 13th Battalion, under his capable leadership, rendered signal service in the defence of Heburterne, an important town north of Albert. For this operation he was mentioned in Sir Douglas Haig's dispatches.

On October 5, 1918, he left the battalion with which he had been associated since its inception, to return to Australia on 1914 leave. The following are the decorations gained by this distinguished officer:

Awarded the White Eagle of Servia, December, 1916; Military Cross, January, 1917; Distinguished Service Order, June, 1918; four times mentioned in dispatches, June 1917, January 1918, June 1918, and January 1919.

His main genius lay in his wonderful power of organisation. To this was added a command of men and a fearlessness that could not but hold the respect of all who came in contact with him. In the leader of to-day it is the power of organising and planning that is so essential, and it is this, unusual in so young a soldier, that leads one to say in no uncertain voice that in Colonel Marks Australia has lost one of her future leaders.

Memorial Service

There will be a memorial service at St. James' at 4 p.m. next Sunday, when it is hoped that there will be a good muster of members of the A.I.F. to do honor to the memory of one of their number of whom they can all be proud. LAST SACRIFICE OF GALLANT SOLDIER (1920, February 1). Sunday Times (Sydney, NSW : 1895 - 1930), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article120517286

Gallant Officer Drowned at Palm Beach.

DOUBLE FATALITY.

A gallant but unsuccessful effort to save a woman from tho surf, cost Lieutenant Colonel Douglas G. Marks his life at Palm Beach on Sunday after Lieut-Colonel Marks was on the beach near Barrenjoey Lighthouse, with a picnic party, including his sister, Mrs. Bertie McDonald, and about twenty friends. Not far away from this group; Miss Johanna Mary Rogers, 32, of Catherine-street, Leichhardt was surfing during the afternoon with some friends.

The dangerous parts of Palm Beach are not marked off with flags. The day was very, windy and a rough sea was running, and Miss Rogers was caught in the current and swept out to sea. Her signals of distress were seen from the shore and two men. S. Thorne of Paddington, and E. Walsh, of Eastwood, swam out to her. They reached her when she was about 200 yards off the beach, but, though they tried for about half an hour, their combined efforts could not bring her towards the shore. After a long struggle they become exhausted and had to leave the woman, in the hope that they would be able to get a lifeline on the beach. After a tough swim against the current they landed, thoroughly exhausted.

Colonel Marks was by this time well situation the woman was now in. He was fully clothed, but without stop-ping to take off more than his coat, and though a poor swimmer, he plunged into the surf to her assistance. There were no life-saving appliances immediately to hand, so he took with him the nearest thing that he could find, a length of clothes line. With this knotted round his waist, he battled his way through the breakers and began to swim to where the drowning woman could be seen, evidently in the last stages of exhaustion.

He made a desperate effort to reach her in time but she sank before he could get near her. Colonel Marks was by this time well in the grip of the current. The frail rope to which he had entrusted him-self broke, and he was seen by the watchers on shore to drift further and further away. He appeared to be making a strong effort to got back, but the current was too strong for him, and after he had drifted some distance he was seen to sink.

Later in the afternoon a proper life line was procured, and the body of Miss Rogers was found floating some distance off the beach. Lieutenant-Colonel Marks, who lived with his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Montague Marks, at Lindsay-street Neutral Bay, was only 24 years of age, and a single man.

He served with the 13th Battalion, A.I.F., and was one of the first to land on Anzac. He later went to France. During the war he was awarded the Order of the White Eagle of Servia, and returned about 18 months ago. In civilian life he was manager of the Continental Paper Bag Company. Gallant Officer Drowned at Palm Beach. (1920, February 2). The North Western Courier (Narrabri, NSW : 1913 - 1955), p. 2. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article134214911

The church was filled for his Memorial Service - a report on this:

Tribute to a brave man.

THE LATE COLONEL MARKS. IMPRESSIVE MEMORIAL SERVICE.

An impressive memorial service to the Into Lieut.-Colonel Douglas Gray Marks, D.S.O., M.C., Order or tlio White Eagle ot Sorvla, who was drowned while attempting to save a young woman's life at Palm Beach on January 24 was held at St. James's yesterday afternoon.

Before the time appointed, the church was crowded, the congregation Including a large number of military officers, both of the 13th Battalion, of which deceased had been commanding officer, and of other A.l.F. units. The father, sisters, and brothers of the deceased occupied seats near the nave. There were also present Generals Rosenthal (commanding 2nd Division) and Herring. Lieut.-Colonel Smith and Lieut. Patrick (representing the State Commandant), Commanders Spain, V.D., and Lambton. V.D., representing the Commonwealth Naval Forces, and Colonel Murray, V.C. (13th Battalion).

The service was marked by simplicity and great fervor on the part of the congregation. The hymns were "Fight the Good Fight," "Nearer, My God, to Thee," and "Abide With Me." Chaplain-General Rose officiated. A large number of people were unable to gain admission, and remained in the vicinity of the porches.

Buoyancy of Youth.

Speaking from the text, "Come, and Follow Me" (Matthew, ch. 19. verso 21), Chaplain Wray, who had served with the 13th Battalion in Gallipoli, Egypt, and France, contrasted the lives of those who followed this call with the lives of those who spent their days in selfish money-getting. He did not hesitate in taking those words to one who had laid down his life for the sake of others, and in applying them to the- young man they honored that day.

Colonel Marks had heard the call to defend the weak and the helpless, and to fight for freedom and peace; they might truly say of him that he never thought of himself, but took up the Cross "In a holy cause to follow Christ's way."

Colonel Marks was a young man, hardly more than a boy, when the call came, but, in him, as in so many young Australians, it touched an undreamt-of undercurrent of patriotism and strength which transformed youth into manhood. But he did not ever lose the buoyancy and spring of youth, and rose magnificently to what turned out to be man's work.

Ono of the earliest of the original 13th Battalion, he throw himself with characteristic energy and enthusiasm into the training work, and he embarked, on December 22, 1914, holding the rank of lieutenant.

Two things about Colonel Marks had struck tho speaker while in Egypt— his keenness and enthusiasm for his work, and his zest and enjoyment of life.

Courage and Resource.

In Gallipoli Colonel Murks had been fortunate in coming unscathed through the first terrible weeks, and he was promoted adjutant, with rank as captain. At Suvla Bay his cool courage and ready resource were noticeable. In France, while major and second in command, he was severely wounded by high explosive, but the clean, healthy life he had always lived served him well in this crisis, and he made a wonderful recovery.

Before long he was— at one of the earliest ages for such a position— appointed commanding officer, and throughout the greater part of the strenuous times of 1918 he led the battalion In Its many victories till, just before the armistice, he came back to enjoy a well-earned spell.

Colonel Marks made good, taking up again his civil life, and gave every indication of being as efficient and forceful in the ways of peace as he had been In the stern paths of war. His life was opening out, full of promise of usefulness and happiness, when once again the sudden call came to him to go to the weak and helpless, to a woman struggling In a treacherous surf. It was a fine thing to gone, and though they grieved at his want of success, they could not be anything but very proud of their comrade. Colonel Marks went to his death in that same glorious spirit of courage in which he had answered the call.

General Brand and General Monash had spoken in terms of the warmest admiration and appreciation of Colonel Marks' services. He (the chaplain) had also received a telegram from General Birdwood, as follows: —

Greatly regret the death of a gallant comrade In Lieutenant-Colonel Marks. It was a splendid act of self-sacrifice, in keeping with his military career, and a fine example to his men.

"Como, follow Me,"- concluded the chaplain. "The call applied to each one of us. The world is crying out for those who will live for others. What a glorious opportunity for each of us to answer that call!"

The benediction was pronounced, then, clear and shrill, followed "The Last Post," sounded very beautifully by a trumpeter in the gallery while the large congregation reverently stood.

A verse of the National Anthem was sung and the organist played the "Dead March" in "Saul, the congregation standing In silence. The late Lieutenant-Colonel Marks would have been 25 years of ago on March 20 next. He enlisted on September 14, 1914, and was severely wounded at Bullecourt on April 11. TRIBUTE TO A BRAVE MAN. (1920, February 9). The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1883 - 1930), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article239665790

PBSLSC Members clubhouse (old Chorley's home) has a permanent honour to members who served in WWI and WWII

Excerpts from Jean Curlewis' 'Beach Beyond'

NB: The Pittwater Online News copy of this book has been donated to the Avalon Beach Historical Society for community access to this work. The ABHS office is within John Stone's photography shop in Bowling Green Lane, Avalon Beach.

NB: The Pittwater Online News copy of this book has been donated to the Avalon Beach Historical Society for community access to this work. The ABHS office is within John Stone's photography shop in Bowling Green Lane, Avalon Beach.

The book was serialised and run by the Sydney Morning Herald during 1923 for those who like to delve into the NLA's TROVE.

In Summer Houses In Pittwater: A Cottage Of 1916 And Palm Beach House and in Pittwater Summer Houses: The Cabin, Palm Beach and The Pink House Of The Craig Family there are a few insights into some of the earliest holiday makers at Palm Beach.

BEACH BEYOND.

BY JEAN CURLEWIS

[ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.]

CHAPTER I. MONDAY.

It was a Monday when things began, and the atmosphere was—well, Mondayish.

That is to say, instead of springing brightly and enthusiastically to work after the refreshing rest of the week-end, everyone was tired, everyone had had a scrambled breakfast and a rush for their trams, and every single one of us was meditating dispassionately on the fact that, with the solo exception of himself, our office staff was the least interesting in Sydney. I remember feeling it as a personal grievance against Kennett, the man at the next desk to mine, that he hadn't got a new face or a new voice or at least a new tie during the week-end.

It was always like this on Mondays—quite probably it is also like this in every other office in town—and by lunch time the feeling invariably wears off. But this was the first Monday in September and therefore worse than usual. I don't know—it was still winter,

but there were occasional drifts of warmth in the air and a faint smell of—I can't analyse it, but it was a cross between the smell of something that happened a long time ago that you can't quite remember and the smell of something that is just going to happen, but you don't know what. Mixed with just a suggestion of wood smoke, as if someone had lit a handful of gum leaves on a far off hill as a signal to you that it was time to start.

But where to start for I didn't know.

Not that I wasn't keen on the office work. I was. I sacrificed three evenings a week to improving my mind, had all the orthodox in-tentions of becoming managing director, and had laid out four and sixpence on a pocket "Message to Garcia" and an "If" printed on a card in three colours to hang over my dressing table.

But if one comes straight from school to an office without having ever been anywhere, seen anything, met anyone, done anything in parti-cular, then on the first Monday in September one is apt to be restless.

However, I settled down to my desk in a resigned, fashion, and for two hours things were much as usual.

And then the clock struck 11, and, as if it had been the bell rung before the curtain rises in a theatre, the play began.

The first entrance was made by George, an office boy, and his opening speech was "Mr. Massimer wants to see Mr. Merrick."

I jumped. I had been in the office of Massimer and Massimer, for a year, but Mr. Massimer had never before expressed any de- sire for heart-to-heart conversations with me, I had said "Good, morning" to him twice and "Good night" perhaps three times. Not oftener, for, the simple reason that he generally arrived at the office in his Rolls about the time that I at home was beginning to think of shaving, and left it anywhere between 7 at night and 2 the next morning. And mean-while one would have had to hew one's way through a squad of lifeguards to get within shouting distance of his room.

And now Mr. Massimer wanted to speak to Mr. Merrick. So far as I could remember I had done nothing meriting dismissal, and on the other hand I had certainly done nothing worthy of promotion. In either case Mr. Massimer would never have even heard of it.

Naturally everyone began to be weakly funny, and Kennett at the next desk inquired solicitously if he could convey my last words and farewell messages to my family.

(All the same I think he got a shock an hour later when George brought him a note from me with "Will you send this to my aunt. Tell her I hadn't time to say good-bye" scribbled on the outside.)

I have vague remembrances of proceeding up the stairs trying to look as if I dropped in on Mr. Massimer every morning for a chat about gardening or the European situation, but only succeeding in looking self-consciously aware that everyone from the typists to the liftboy was staring at me in an awed fashion, speculating inwardly as to my probable fate.

And then, almost before I knew it, I was leaning back in an armchair and Mr. Massimer and I were smoking cigars together.

For quite 15 minutes we chatted together in a leisurely fashion. He asked where I had been at school and discussed the com-parative merits of the various big schools— asked how, I liked the office work, told me some interesting inside information about things, of which in the lower office we only knew the outlines, and commented on the hint of spring in the air.

Just then he broke off.

"Do you know where Beach Beyond is?" he asked.

"I never heard of it, sir," I said, after a minute's vain endeavour to recall the name on any of the office documents. Was my ignorance going to prove that I took no interest in the firm's work.

But he did not seem displeased.

"You take a North Coast train," he said, and stared out the window which faced north, as if he were looking a long way off, "and get out at a platform called Finn's Siding. You'll see a sort of store—go in and ask for Old Jimmy. He's got a waggonette of sorts, and he'll drive you to the end of the world. Beach Beyond is twenty minutes farther on."

Not quite knowing the correct response to make when a man of Mr. Massimer's standing gives one directions for a place 20 minutes past the end of the world, and, more over, seems to take it for granted that one is about to proceed thither, I said nothing.

"This is the Beach," continued Mr. Massimer, and handed me a framed photograph which had been standing on his desk with its back towards me.

So for the first time I looked at Beach Beyond.

It was a queer photograph—whoever took it was an artist. It was only a cabbage palm, black and lonely against a waste of beach and a tumbling line of surf, but it had caught the atmosphere that later I was to know so well, yet never to be able to describe. ("It's the 'beyondness' of it, as it were" as Egbert said a few months later, with characteristic idiocy, but as a matter of fact that came closer to the mark than anything else I have heard.)

Mr. Massimer went on speaking.

"It's this way, Merrick. At Beach Beyond Sir Julian Whitcombe, Dr. Fenning, myself, and five others have built a small week-end surfing colony. We each have a bungalow, and our wives and children are there most of the hot weather, the rest of us motor down for week-ends. Until last week we have never had even an alarm in the surf, possibly because none of us are sufficiently expert surfers to venture out very far. But last week we had a most ghastly tragedy—the newspapers only gave it three or four lines in the casualty column, but it was none the less horrible."

He paused frowning, as if at an ugly memory.

"All our women folk," he continued, "and the children and luggage had just motored down to take up possession for the summer. One of the chauffeurs went in for a swim, and was snatched off his feet within a few yards from the shore, carried out to sea as if by a mill race, and drowned in a few minutes in spite of the other chauffeurs' extremely brave attempts at rescue. But as they had no surf-line and were all bad swimmers it was hopeless from the first. Apparently a fast-running channel had suddenly appeared in the very spot where we had bathed last year."

"Channels often come and go like that," I remarked. "A storm will dig out a perfect death trap in one night, and even quite a mild wind blowing up a sea from the same quarter for a couple of weeks will have the same effect."

"Apparently it's not the first time a channel has appeared in that particular spot," said Mr. Massimer, "because since the accident we have heard a confused story from neighbouring fishermen that 20 years ago a boy was washed out in exactly the same place. There is some doubt that the story is true, but I owe it to you to tell you."

I said "Yes," though I did not see in the least how it concerned me.

"Naturally," said Mr. Massimer, "we must have a trained life saver at once. I shudder to think of the risks our wives and children have been taking all this time, and I feel almost personally responsible—though legally, of course, no shadow of blame attaches to me —for that poor chauffeur's death. I have sent for you this morning to know if you will take the position of life saver for this spring and summer. I will see to it that you lose no seniority in the office. We are offering eight pounds a week and quarters."

"You can get a first-class professional for four ten," I said. I had to tell him in common honesty.

"Perhaps. But you must remember that very few men would come to Beach Beyond. It's practically cut off from the world, and I'm afraid that there won't be any holidays in the six months. The hours are six to six, with scarcely breaks for meals, and I need hardly tell you the work is monotonous—most of the time you will have to spend on the sand looking at the water without even the pleasure of going in the surf yourself. Your only chance of diversion will be occasions which God grant may never arrive, when you will have to put up a lone hand fight against an ugly current with no trained team on the line behind you like you had last April at Manly."

I stared a little, and he smiled.

(To be continued.) BEACH BEYOND. (1923, March 9). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16064524

BEACH BEYOND.

BY JEAN CURLEWIS.

[ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.]

CHAPTER XI.—Continued.

It was good to round the point and see a vista other than the one that I had stared at from the beach for so many weeks. The rocks were hot and satisfying under my bare feet, and I had never seen such rich coloured sea-weeds. Wine-red and rusty gold, they swung lazily in opal-coloured water while the surf shot up in pillars and columns of white marble that crumbled suddenly into spray like finest lace. On my right the cliffs soared chocolate-purple a good sixty feet.

It was easy enough going, almost smooth, with no big boulders to scramble over or circumnavigate—nor in the shelter of which a man might camp. So far, at any rate, Egbert was right.

And when I finally did come to a great fortress-like volcanic formation, beyond which I had a moment's hope I might discover some-thing, I found on scrambling up that he was right again. The far side dropped straight into the gap or channel, of which both he and An-drew had spoken. And, though ten yards away the rock floor began again smooth and invit-ing, the intervening space simmered white, furious, and utterly prohibitive. And there could be no crawling along a ledge at the back of it for the simple reason that the cliff was as smooth and bare as razor blade.

I was all the better pleased—it narrowed my search to the comparatively small area which I had just traversed. And, as those whom I had come to seek were obviously not camping on the ground floor-well, as Egbert would have remarked, the word "ladder" pos-sessed a certain significance.

Very slowly I began to walk towards the beach, scanning the cliffs with eyes that endeavoured to probe into every scar and seam and shadow on their faces that might or might not screen the mouth of a cave.

But I reached the point without discovering a hole that would shelter even a bird. Patiently I turned and began to walk back again, hoping that, by some trick of sun or shadow, it might be visible from the north when imperceptible from the south.

But all too soon I found myself back by the fortress rock and the forbidding channel. I scrambled up again, and for a few minutes stood gazing absent-mindedly into the yeasty water.

And then suddenly my throat began to dry and my body to stiffen. Through the clash of the surf my ears had caught another sound the desperate clanging of a bell—the bell of the wrecked ship Lahore. On the beach that I had deserted someone was fighting, choking, drowning in the death-race of the current.

CHAPTER XII.

"BELTMAN GO."

With every pulse in my body bumping and thundering, I began to scramble down the rocks.

By the cuts and grazes I found later on my arms I must have made a rough and reckless passage of it. I only remember that I jumped the last few feet—then came the bright wicked green of the conjerboy bed where my feet landed, and the silky slipperiness of it as my toes fought to grip. Next I remember the warm rock rushing up to meet me as with the bell still clanging in my ears I pitched face forward into darkness.

How long I lay there I don't know. Three minutes perhaps. I only know that when I opened my eyes again everything was very warm and still and my eyes were staring up into the cloudless blue of the sky watching with lazy pleasure a fish-hawk soar and bank, nose dive, and recover again, with scarcely a beat of its superb and powerful wings.

Then little by little the silence began to trouble me—my dazed brain commenced to stir uneasily. Surely there had been a noise not so long ago—a noise that—and then with a cry I knew. The bell—and it had stopped. With blood streaming in my eyes I staggered to my feet—and nearly dropped down again so fierce was the pain that stabbed at my left ankle.

But the pain vanished. I was running clumsily towards the point—I was round it with a brain that was curiously calm. I was taking in, as I ran, the details of a scene as ugly as any lifesaver could wish to see.

There were the white sand, the white lines of serf. Well beyond the outermost line two black heads bobbed and disappeared and bobbed again while the arms attached to them seemed to beat feebly. Between them and the shore floated something I recognised as the box of my boxline. Egbert was nowhere in sight.

Also between them and the shore—right in the line where the breakers dumped most savagely. Silas P. fully dressed with the belt of the reel line slipped over his shirt. Was getting knocked down, struggling gamely to his feet and getting knocked down again with the monotonous regularity of a ninepin.

Knee deep in the shallows, Mrs. Massimer, Mrs. Fenning, and Mrs. Fielding were trying with inexperienced hands to pay out the line to him, while Mrs. Norris ran it off the reel.

"Let the reel run—help with the line," I shouted to her as I ran. "And make the others come out of the water." They were ignorant of the first principle that a linesman must always be high enough on the beach for the breakers not to block his view of the beltman.

I splashed past them, ran through a smother of broken water, and came up by Silas.

"Give me the belt," I panted.

I suppose it was the blood on my face that made him think I wasn't fit to go out, for the game old lad shook his head and tried to battle on.

There was no time to argue. I dived through an oncoming wave ahead of him, and as he, less experienced, came up staggering from the shock of it, I knocked him back-wards and tore the belt over his head. I had to handle him pretty roughly in the process, and I turned my back on him with a horrible doubt that he would be able to get to shore again.

Then lifting one arm as a signal to Mrs. Norris for more line, I pushed sideways to the channel, instead of forward through the breakers.

Generally it is a ghastly feeling to have the current snatch hold of you and suck you out like a leaf, but this time I surrendered thankfully. It was running like a mill race, and I had a second's terror that in another yard the unattended reel would overrun, jam, and pull me up with a jerk. But in the same second I found myself level with my patients, and felt the current slacken its grip.

And now as I swam towards them I saw for the first time who they were. Of all the people in the world—Andrew and Egbert.

They had drifted apart, but both were almost finished and as I covered the inter-vening space my mind worked in an agonised fashion—whom ought I to take first? Egbert was far the weaker of the two—how he came to be still alive right out here was more than I could fathom, but to my amazement Andrew seemed in oven worse straits. Also he was the nearer to me, and Egbert was making feeble signals to me to take Andrew first.

An idea flashed through my mind to put the belt on Andrew, have him pulled in without me, while I tried to drag Egbert in without a belt. But that I knew was hopeless—that way all three would be drowned.

Then the question was suddenly settled for me. By some heaven-sent chance the belt of the boxline—though the line was torn away—drifted against me, and at the same time Andrew's head disappeared. I caught at the shoulder-strap of his costume just in time—gave the box-line a feeble shove to-wards Egbert—then, grabbing Andrew more firmly, I lay back in my belt and gave Mrs. Norris the signal to pull in.

There was nothing else to do, but if I had been Egbert's murderer I don't think I could have hated myself more than that minute when I deserted him. Even if I managed to get out again I knew he would not still be there. To make things worse, he gave me a faint smile, and I saw, rather than heard, his lips frame the word "Cheerio."

Then I forced him out of my mind, and concentrated on the task of getting Andrew in. We were certainly travelling far from fast—the pull of feminine hands on the line was very weak and I could feel they were pulling out of time. Also they could not judge the waves, and instead of slackening up when a dumper broke over us, they dragged us through it, nearly drowning us both. And my fall was beginning to tell.

By rights I should have pushed my patient, who was now limp and unconscious, up with both hands each time a wave came, and gone under myself, But I had need to husband my strength if I were to make a return trip for Egbert. Consequently, I thought it was a fair thing to give us alternate spins. Never, it seemed to me, had the waves come so close together. Line after line seemed to crowd down on us without a second's respite, and every time I went under I thought my lungs would burst.

And then just as I seemed to have been in the water a hundred years, I found people all round me—Mrs. Fenning and the rest up past their waists in water. They took Andrew from me, and, putting down weak legs, I touched the blessed bottom. (To be continued.) CHAPTER XII. (1923, March 22). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 5. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16056693

Dedication ceremony in: Palm Beach Pavilion Renaming Dedication Honours Lieutenant Colonel Douglas Marks DSO, MC