The Tourist.

Our Pleasure Trip to the Hawkesbury.

By Grandmamma.

' If, sick of home and luxuries, you want a new sensation,

And sigh for the unwonted ease of unaccommodation—

If you would taste, as amateur and vagabond beginner,

The painful pleasures of the poor, get up a picnic dinner!'

Such was the advice of Horace Smith in days of old, when we were young, and rather failed to appreciate his pleasant sarcasm. But as years go on, and the romance of youth goes off. in company with lissomness of limb and elasticity of spirit, his words of wit and wisdom find readier echo in our thoughts, and 'The days when we went gipsying, a long time ago.' assume a somewhat fabulous halo —even a lunar halo— as they are pictured in our sane and sober elderly memories. A recent experience of our own suggests a variation on the above-quoted verse :

If, sated with the loveliness of Sydney's peerless haven

You covet sight of other scenes more rugged and unshaven—

If steamers swift and clean and trim you value not a stiver.

But like them slow, and black and grim, go up the Hawkesbury River!

We did, and as a member of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals I am constrained to say to all who may think of doing likewise, 'Don't' — until a thorough reformation and rearrangement in the modes of transit be effected. On last Friday afternoon, our small party of three, viz., Mr. and Mrs. B ? and 'Grandmamma,' steamed pleasantly to Manly Beach in the Fairlight, in time to 'catch the coach' for Newport, as prescribed in our sailing directions. These assured us that the trip was always accomplished in the easiest and pleasantest manner, and that we should arrive in town on Saturday evening. How delusive these promises proved will be seen hereafter. Two rough vehicles were in waiting at Manly, and we scrambled into the better looking of the twain, drawn by four horses, to be immediately taken to task and roundly rated in no measured terms by the driver of the two-horse machine for not going in his coach and to his 'hotel,’ he seeming to claim a monopoly of all Hawkesbury-bound passengers, whether he had room for them or not. Dire and dismal were the threats he hurled at us, and which rumbled in our rear as our good-humoured 'whip' drove off with us. The road was good, and glimpses of grand shore cliffs and headlands, and bits of lovely unspoiled ' bush,' bright with exquisite native flowers (which, alas, we might not stay to gather and delight in), pleasantly beguiled the way, and softened many a jolt ; whilst the discovery that two other lady passengers (visitors) were friends of mutual friends in various parts of Australia made a cheery, chatty quintette of the performance which had begun as a trio. 'Crack went the whip, round went the wheels, Were never folks more glad. They told the deeds of long ago, And merry tales and sad.'

Presently we splashed through a wide lagoon, looking, or at any rate intending to look, as though we found it quite an agreeable incident, but holding on tightly all the same, and hailing our return to dry land again with little gasps of satisfaction. The appearance, not far from the roadside, of a plant of the panoanus was a sensation. We greeted it with a cry of joyous welcome, as the advanced guard of those tropical glories which previous visitors to this region had glowingly described. The graceful plumy crowns of the cycas, too, were abundant in parts of the bush as we neared Newport, and we revelled in rich anticipation of the wealth to come.

Our conveyance brought us to the steps of the only visible house, a new-looking abode, of the usual country inn type, where, after considerable delay, a rough (very rough) meal was served; chops, coarse and nearly raw, over which the contents of the frying-pan had been liberally bestowed, and a piece of beef, which seemed to have been just introduced to a fire, but not permitted more than a brief acquaintance therewith.

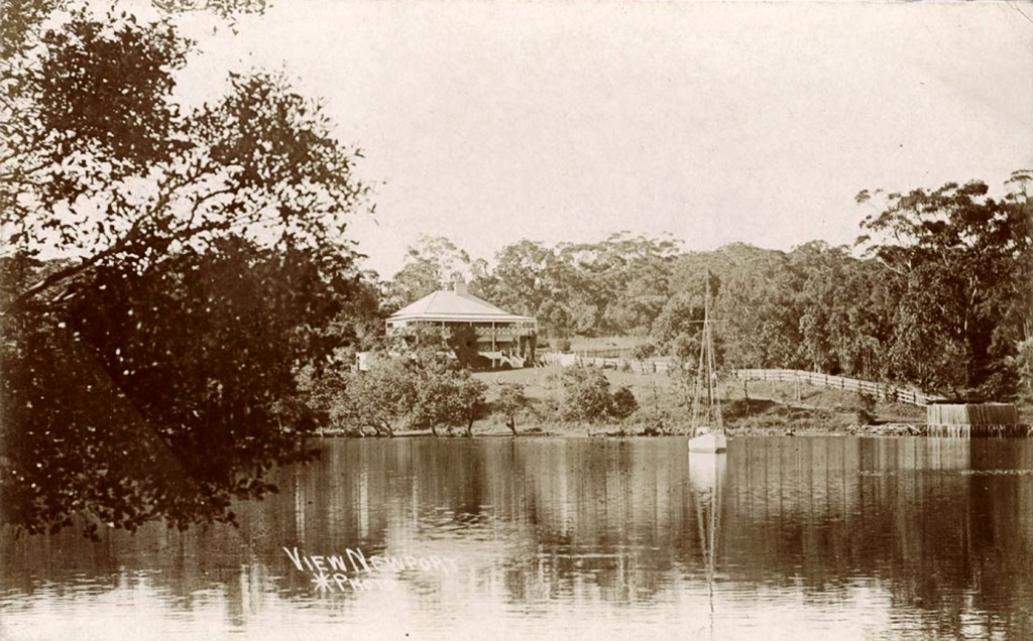

Scott's Hotel from Broadhurst image 1900-1927 106124h Courtesy State Library of NSW.

Henry King Photographs, courtesy National Library of Australia and Pittwater Image Library Mona Vale, c. 1900-1910. Top: Bay view House, Newport NSW. Below: Pittwater from BayView House.

But appetite for even a more luxurious repast was destroyed by the announcement that the engineer of the steamer which we expected to take us on the morrow was very drunk at the other 'hotel' (kept by the opposition driver whom we did not patronise), and that he declared the vessel out of repair and unfit for the voyage, whilst darker rumours were soon afloat that he said she would 'blow up.' One version was that he threatened he would blow her up himself, as 'he could swim if others couldn't.' The roseate hue began to fade from the complexion of our hopes, and we spoke of returning to Manly in the morning; but a promise that the tipsy engineer should be well watched, and kept sober when he became so, allowed us still to dream of pursuing our intended course.

Our rooms, though small and scant of comfort, were clean; and our rest undisturbed by any entomological specimens. After a very early breakfast, we were summoned to go on board the steamer, which lay half a mile off, at a rude sort of landing place near the other 'hotel.' With great difficulty and fatigue we made the descent of the steep bank, some 50 feet in height, by means of logs laid at uncertain distances, making a species of stairway, some steps being thrice the depth of others, and all slippery. The captain — whose civility and kind attention throughout we all gratefully appreciate— assured us that the engineer was 'all right,' so, on arriving on board, we picked the least dirty spots to sit in, the deck being strewn over with coal, and off we steamed down Pittwater, at a very moderate rate, but fast enough for one of the party, who, pencil in hand, took rapid notes, rather than sketches, of the ever-changing and most picturesque headlands and islets as we proceeded. A pretty stiff breeze was blowing, and through the broken waters of Broken Bay the little steamer puffed and groaned and rolled horribly.

Elliot Island was long: the central point in our view, and its isolated position seemed, in our perhaps superficial judgment, to point it out as a suitable spot for the storage of at least a portion of the 900 tons of mischief in the shape of dynamite and powder, the expected explosion of which is now so sorely exercising the fears of many a worthy resident in and near Sydney.

The absence of nearly all evidence of population, so far as we could see, and the barren nature of the land around, seem to render it improbable that even in the future any number of inhabitants would occupy the neighbouring shores to be endangered by the proximity of a magazine on Elliot Island. The discovery that two passengers who had come by the other coach to the other hotel were friends from Melbourne, also, like ourselves, 'on pleasure bent,' was an agreeable surprise, and conversation, in often varying knots of twos and threes, went on with animation. As the channel narrowed, the shores gained in picturesqueness, and we understood the comparisons which have been drawn between the scenery of the Rhine and that of the Hawkesbury, but surely they were made by enthusiastic Australians of die 'Marchioness' persuasion, prepared to 'make believe a great deal' on patriotic grounds !

The towering heights, crowned and bristling with fantastic rocks, resembling in many places the ruined fortresses and castles of the old world, are most striking, and we gazed, in keen enjoyment, as cliff after cliff, and crag on crag appeared. But, alas for the imperfections of humanity ! We found that, after doing some 20 miles of ecstasy, the old story of 'Toujours perdrix!' made itself remembered; for there is, it must be confessed, considerable monotony in the general aspect of the wall-like barriers of cliffed and caverned rocks, although, if considered in detail, nature's inexhaustible variety gives to each some special feature.

The few habitations near the river are of a very humble character, and our expectations of seeing orange groves were but scantly realised. The native fig and a graceful pine in some spots gave a pleasant relief to the too common forms and sombre hues of the universal gum trees, but the prevalent browns and dim olive tints of the general masses were most aesthetic combinations, and ' tropical vegetation' was conspicuously absent. Long before we arrived at Wiseman's Ferry the condition of the delinquent engineer had again become critical, and our apprehensions as to progress and safety anything but pleasant. Our landing was effected in very primitive fashion, no attempt whatever had been made to cut down the bank, or to make the most rudimentary stepping-places, but we all had to scramble and claw our way up, clinging to projecting roots or hanging boughs, as we best might.

A walk of half a mile to the inn followed, and then succeeded luncheon, roughly served, but clean and abundant. On returning to the bank where the boat lay, the engineer was found lying on the deck in a hopeless state of intoxication, inert and insensible, he having, as was ascertained, brought with him a bottle of gin which he had finished. The captain said he did not understand working the engine himself, and that he could not take us further. The result of a council of war held on the spot was the decision that we must perforce return to the inn for the night, and that the captain should obtain the services of a sober engineer he knew of, and to whom he went forthwith; and our party, disgusted and disappointed, crawled wearily back again to the welcome shelter of the inn, and severally disappeared from public view for a 'siesta.' After tea we adjourned to the wide balcony to look at the brightly blazing bush fires on the neighbouring hills.

Next morning, Sunday, after breakfast we again walked down to the boat, and found the difficulties of re-embarkation greatly increased by the low tide. A large space of black mud now intervened between the steep bank and the vessel; over this some bits of firewood had been flung down for us to step upon and only the aid of strong and kindly hands enabled the elders of our party to escape being bogged, but no serious disaster happened, and we went on, under the care of the new sober engineer, the semi-sober one frequently and vainly endeavouring to interview the passengers, who very naturally declined to have aught to do with him. Parts of these higher reaches of the river were beautiful, even though but partially discerned through the thick veil of vapour — a most provokingly opaque combination of smoke and fog — and we were pleased and hopeful until, on reaching the end of our voyage at the landing place at Sackville Reach, it was found that the conveyance which had come to meet us the previous evening, and brought a number of passengers to go down the river, by the steamer that brought us up it, had returned to Windsor with its cargo of deluded tourists; and we were left without any means of proceeding, as arranged, to the railway. Another council was held. One passenger, not of our party, a young man, Winded, to walk the 10 miles; but we were (some of us) not young, and not able to be so independent. To land was simply absurd. We could not sit starving on the shore till on some future day (date uncertain) we might be picked up, and returned to our friends. The inn at Wiseman's ferry seemed our inevitable destination once more, and thither we steered, as vexed, humiliated, and indignant a group of grumblers, justified in the very strongest Utterances of our grumblings, as ever had the cup of pleasure embittered and spoiled by unpardonable negligence in those on whom the arrangements depended.

Sackville Wharf, Hawkesbury River, from Scenes of Hawkesbury River, N.S.W. ca. 1900-1927 Sydney & Ashfield : Broadhurst Post Card Publishers Image No.: a105344, courtesy State Library of NSW.

On arriving at Wiseman's, the new engineer positively refused to take us any further, and we as positively refused to put our lives in peril by going in charge of the drunkard. Meanwhile, dinner was an imperative necessity, and all of the passengers, save two, went up to the inn, a buggy having been sent down to convey them in relays. The two who remained, feeling unequal to any exertion, in their weary and hungry condition (having breakfasted at 7, and it was now nearly 4 p.m.), begged that some food might be sent down to them.

The indefatigable sketcher beguiled the first half-hour with a pencil; then the cravings of Nature conquered even love of art, and eyes were strained in the direction of the inn. Poor Mrs. Bluebeard herself could scarcely have uttered in more plaintive accents, 'Sister Ann! Sister Ann! do you see anybody coming?' than our pair of expectants might have been heard to faintly exclaim in turn : — ' Look ! there's something moving. Is it a man? No, its only a cow.' 'Surely that's a human shape. No, it's a stump.' 'There's another figure ; yes, it really moves this way. Is it carrying anything ?' 'I think I see a bundle— perhaps a plate in a handkerchief!' 'Yes, he sets it down as he climbs die fence.' The excitement grew too intense for words. It teas a man!— he had a bundle! There was a plate inside with chicken and bread upon it! Knife and fork came not; but that chicken's bones were picked with a relish that rarely comes to mortal lips in civilised lands, and those two poor sufferers, restored and comforted, could listen calmly to the plans discussed.

At the price of five guineas extra, the sober engineer undertook to see us back to Newport that night. Our Melbourne friends, fearful of the rough, sea and the lateness of the hour, and being utterly weary of the dirt and discomfort of the wretched little boat, resolved to sleep at the Ferry Inn and hire a vehicle to take them to Parramatta (39 miles) next morning. But our party of five remained on board. The return voyage was slow, and after sundown the seabreeze blew very cold. The wooden gridiron-seats were not couches to satisfy a sybarite, however one might twist and turn and ingeniously feel for a batten softer than the rest. Broken Bay was what an old non-nautical Scotch servant of ours in the old days termed 'vary lumpy,' and the little vessel tossed and rolled amongst the lumps in so unpleasantly active a fashion that, had the exercise continued long, it would have had serious results; but we fixed our gaze either on Venus, brilliant above us, or on the bright red lighthouse star on Barrenjoey, and came safely into smooth water, going, I should think, about two knots an hour. Remembering vividly the terrible steps at the Newport landing, grandmamma had determined to roll a sail about her and lie on the deck till daylight, but the good captain pledged himself that we should be helped safely up, and well redeemed the promise, with the ship's lantern carried in front, to show the 'course' to be steered.

The time being nearly midnight, the people of the inn had been long in bed, when the yelling steam whistle, telling of our approach, aroused them to prepare supper and beds. It would be hardly fair to criticise preparations so hurriedly made, however many their shortcomings. We had this and a half hour's rest, and rose at 5 on Monday morning. It was the opposition inn to which we had come, as being the nearest to the landing, and in the opposition conveyance, which exceeded, in ragged roughness of form and material, any other conveyance we ever beheld, we reached Manly, very thankful that our expedition had safely ended; and resolved to give friendly warning to others: that, until sober and civil persons are employed by the proprietors of all conveyances concerned, and punctuality, safety, and passable comfort assured to passengers, the grand scenery of the Hawkesbury had better remain unvisited. The Tourist. (1882, October 14). The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 - 1912), p. 638. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article161925522

Wiseman's Ferry, N.S.W. circa 1900-19127 - Sydney & Ashfield : Broadhurst Post Card Publishers, Image No.: a106388, courtesy State Library of NSW

This is one of many retorts, over many years, to an Argyle style report:

A Pleasure Trip on the Hawkesbury,

TO THE EDITOR OF THE SYDNEY MAIL.

Sir, — We notice in your issue of the 14th instant, under the nom de plume of 'Grandmamma,' a long and plaintive story, commencing with the flourish of a poetical pen. Judging from, the manner in which this story is told, we should think that 'Grandmamma' possessed one of those super-poetical natures easily disturbed by common occurrences, and certainly unfitted to give to the pleasure-seeking public a fair idea of a trip on the Hawkesbury, under ordinary circumstances. The drunken engineer threatened to blow up the steamer, but 'Grandmamma' was Ices ambitious and contented herself by ' blowing up ' everybody in connection with buggies, coaches, steamers, and hotels en route. Now we have done the Hawkesbury, and although not wishing to assert ...we have, however, succeeded in enjoying ourselves thoroughly. We did not notice the roughness of the vehicles at Manly, neither the necessity to 'scramble' into them. We did not find the slightest cause for nervousness in crossing the lagoon— entre nous,' Grandmamma' must have been asleep when passing the stranded Collaroy, and the awaking -when in the proximity of the pandanus must have been the 'sensation ' referred to.

We happened to stay at the opposition house at Newport, and without delay were served with dinner, consisting of fowls and roast beef, the latter a little too well done, if anything.

Picture of Newport hotel above is dated 10.7.1884 by Robert Hunt and courtesy Pittwater Local studies - Historical Images, Mona Vale Library.

After breakfast next morning, at the very early hour of 6, we made for the steamer, much fearing the descent of the steep bank. It is true we did not find marble steps, but very convenient ones, and were at a loss to know how other than a confirmed cripple could complain of the fatigue and uneasiness of their descent. We found the steamer all that could be desired, even to having carpets spread on the 'gridiron' seats, so particularly noticed by ' Grandmamma,' and the engineer was perfectly sober. After passing through beautiful scenery on either side, we arrived at Wiseman's Ferry — a distance of some 50 miles — at 12.30 p.m. Here we found a substantial stone wharf, upon which the passengers stepped directly from the steamer, even at low tide. As the steamer could not go alongside the hotel, and there were no rails laid for the hotel to run down to the steamer, we were obliged to walk some half-mile to the latter. A well served good, substantial lunch was ready, and we were attended during the repast. Finding also the hotel very clean and comfortable, and being informed by the landlord that he drove folks to or met them by appointment (by telegram, as there is only twice a week delivery of mail) at Windsor gratis, if they wished to stay here a few days, and not a week, as the steamer service would oblige them, we readily took the opportunity, especially when considering the rest of the river was more or less indifferent in respect to scenery. In this we had no cause for regret. We stayed some four days, during which time we had a boat and buggy at our disposal, and were able to make very pleasant excursions inland and down the river. After paying a very moderate reckoning, we were driven into Windsor and thence caught the train to town, having firmly made up our minds that, with your kind permission, we would first challenge ' Grandmamma's ' disparaging comments, and then give friendly warning to others that, if a few days are no object, by far the best (and also the cheapest) way of seeing the Hawkesbury is to adopt our plan and make Wiseman's Ferry the base of operations. — We remain, Sir, yours truly, COMMONPLACE YOUNG MEN.

A Round Holiday Trip.

By “IBIS”

I had often heard of the beauties of the Hawkesbury, the afore irresistible charms of Kurrajong, so resolving to make a round trip of it, we arranged a party and started one fin morning in spring. I give my experiences with the charges or cost of the flying visit, hoping it will be valuable information to my readers, and that many may be enabled to do as we did in the coming Christmas holidays.

We reached the Royal Hotel, Richmond, at 11 o'clock, where, after being kindly attended to by the excellent lady of the house- we were thankful to lounge on the balcony and rest after the tiring events of the day. ' The next morning at half-past 9 we started by coach, Powell's Royal Mail; for the Kurrajong. This drive takes two hours and is a very pretty, pleasant road. The charge is moderate, about 2s, and the coach stops at Powell’s homestead, where you can have a good dinner, cleanly served and not expensive, and any amount of any fruit in season, English or tropical.

When you reach the heights of the Kurrajong the view of the lowlands is very fine. You see Richmond and Windsor lying little patches in a field; the Nepean winding through the plain like a twist of macaroni — no larger, so you may guess the distance you see Parramatta and the adjacent little settlements, and (the 'Railway Guide' informs me) 'even the locality of the metropolis itself”, for this I cannot vonch, as I did not observe it. As I stood upon the height gazing at the vast stretch of country before me, I was forcibly reminded of the temptation of our Saviour on the Mount. The most beautiful large tree ferns grow at the Kurrajong, and are easily procurable. Also the waratah, or so-called native tulip.

The next day we wandered about Richmond. This is quiet little place, whose-growth appears to have suddenly, stopped some thirty or more years ago. And the present inhabitants seem quite content to leave well alone. Business seems stagnant, and quiet content reigns over all. The park, or cricket and sports ground, lies in the centre of town and is a goodly square of ground, with a large ring like a mammoth circus fenced off from the trees and seats. The ground here is smooth and the grass green. There is not much in Richmond for sightseers to see, for it is built on a portion (very small) of the immense plains. Windsor also'is built on the same a few miles on — three or four, I think; but, then, Windsor is worth anyone's visit, if it is only to see the fast-falling old records of the past days of this colony. Windsor is one of the very oldest settlements, ranking almost with Sydney and Rose Hill, or, as they call-it- now, Parramatta.

We left Richmond for Windsor on Saturday afternoon by the 4 o'clock train,, and reached there a few minutes later. At the station waiting the arrival of the train were two omnibuses; and some safety cabs. I felt we were in a recognised town again, and felt sorry as I looked around and saw the substantial buildings as far up as eye could see. I was somewhat astonished too; for after Richmond with its placid quiet air, which put me in mind of a boy dozing at his work on a Summer's day, or a bullock driver asleep in his dray while the team pulled lazily on, the little town is there, but everything is green — grass even growing in its principal street; it seems dozing under the heat of the summer's sun. Now, Windsor, although so near; is entirely different ; life here strikes one as life — not existence only, but work. The very women who stand at their door to see you pass are busy — either with nursing or sewing. Sister towns, Windsor appears like a hungry ratter looking for his food; Richmond like a pampered overfed pet sleeping on his cushion. As we drove up the street I saw that most of the buildings were old. I felt a feeling akin to awe possess me as we went on. Up the old street on either side the old houses stood, thickly interspersed by the bright fresh ones, some with every pane of glass out and only the sash in the windows, others with the shutters hanging by one hinge, others in order but still unmistakably old. There seemed a forlorn air of neglected old age about them that appealed to the sympathies. They seemed to say, 'See, here we are ! standing still ; and each one us could tell many a tale if we chose.'

The people of to-day vanished, and I saw the inhabitants of the past once more come and go in the streets. The phantom faces looked out of the glassless windows at rue. A detachment of the old 109th marched down the street. I heard a clanging sound. Lo ! a body of convicts, with their grey or yellow dress, with the broad arrow-branded on the back, chained together, moved past with their armed guard. Yet another came on-. This time they took the place of four footed animals, and were drawing up a dray and its load. Now a prancing, champing horse came up the road, its trappings and its rider's dress glittering in the sun. He was an officer of the regiment sitting firmly upright in his saddle in all the pomp and glory of fall regimentals. Oh! people of the past ! Oppressed and oppressors, sinners and stoned against, how paltry and fleeting your sorrows and chains appear now ? 'Twas but a little time even at the best. You have passed away, and the earth knows you no more. Only the effects of your works remain. You have passed, even as we are doing, like a shadowy panorama.

The coach stopped at the Royal Hotel. This is a square brick building, still good, with a verandah round two sides, it ends the street, and was aforetime the officers' head mess-quarters. The old barrack and gaol are just round the corner of the opposite side, and would have been, I conclude, in sight of this house when the officers had it.

Opposite one side of the verandah is a smallish green field, fenced in by a white fence. Here stood the whipping post, the call bell, and the stocks of old memory. The present holders of the hotel remember all three standing, and of being in use.

Just below this is a branch of the river, almost dry as I saw it, edged on each side by large old weeping willows, brilliantly, brightly green. I have never seen such a multiplicity of weeping willows as I saw here, and on the Hawkesbury large graceful trees.

' 'I wonder' I wondered aloud, 'why they planted so many willows ?’

‘Because thems the weeping willows,’ returned a voice at my back. I looked round, and leaning against the inside fence was a little, dried-up looking old man.

'But what good do they do ?' 'Why, they show to the world the sorrows of ‘em as planted ‘em living momenters of tha old times.’

'But they weren't all sorry.’

' Every man Jaek on 'em, mum, frees or lags. Everyone on 'em.'

He said this with an uncompromising firmness that forbade argument.

'Why, the officers who lived here were not sorrowful? What had they to be sorry for ?'

'Most o' them tress were planned by the hoffisers. Out o' that werry door as fine a young gent as ever lived was carried in his coffin wi' a broken heart. Not sorry ! Why, sorrow an' New South Wales camped at the same fire, in them days! '

' So you remember them ? I asked,

'Remember 'em? I should think I did! I onghter when I lived in 'em!’

'I feel much interested in the past, and would be very happy if you would tell me something of it, but not all of suffering.’

‘Why, twas the time of suffering. If that there piece of ground opposite could 'up and talk it could tell of suffering. Often the flogger has dyed the grass with the blood of man. Talk of suffering, why, if all the tears that were cried in Windsor could flow down together, they’d make as big a flood as ever swamped the town, or overflowed the banks of the Hawkesbury.'

….

Just then the tea bell sounded, and I was reluctantly forced to leave this entertaining fellow. I found out that the coach, for the Hawkesbury left at 7 o’clock on the following morning and if I didn't take that I would have to wait till the following Sabbath morning, as it only went once a week. We decided to leave in the morning. Intimating our desire to our hostess, she informed us that punctually at 7 the following morning we would have to be standing in the verandah, ready to mount, when the coach drove round ; for its driver was a very irrascible man, by the name of Paddy, and known far and wide for the hotness and strength of his temper, having frequently driven off without his passengers, loudly and often expressing his resolve to ‘wait for nobody’, even if this 'nobody should be the Governor of Australia’. At a few minutes before 7 the following morning we were standing on the verandah, awaiting the coach, and certainly lost no time in scrambling up into our seats. This was agreeable to the driver, so he greeted us by glancing round and giving us a grunt. This the hostess of the Hotel informed me, in a whisper, was a great unbending on Paddy's part. We were off, and crossing the bridge passed down-a very pretty road, still plentifully besprinkled with weeping willows. This drive is one of 10 miles, and was done by Paddy in fine style, and well within the two hours. He very politely came and helped us down, carried the box on board the little steamer that waited alongside the bank and returning, escorted us on board.. This unwonted conduct caused the captain of the steamer and his wife to stand aghast; they stared open mouthed at us.

But Paddy soon brought them to their seinses by telling them if they were one minute behind next time next trip they could stay away altogether or let the passengers find some other means of going over the 10 miles to Windsor; they wouldn't, get his car. The captain mildly explained that last trip the engineer had been under the potent power of ardent spirits. ‘I don't care, drunk or sober, if yer not here to the minit you don't get me, so mind’. With this parting 'warning Paddy took himself off.

The little steamer lay against the log that does duty for the quay. There was on board, besides, 'our party.' the captain's wife, the captain, and his one solitary help. This person was A.B., engineer, steward, cook, and first mate rolled into one. Like a generally useful help, he was remarkably dirty and greasy. He was sitting forward with his arms' folded, dozing, when we came on board. He looked out at us with one eye, but immediately closed it, and his head fell on his chest, again. His appearance was very warmly received by one of our party, who fondly hoped there might be some after dregs of drunkenness left in him sufficiently strong to cause him to play some tricks. This wish, I am glad to say, was not gained, as the present party was not the one who had so enlivened the trip of the preceding voyage. He was sleeping off the effects of his alarming carovsal in the little slab hut on the bank, and the captain's lady informed me she had not yet recovered from the frights she had received, nor did she expect to for an indefinable period.

Be it known, the Hawkesbury River is one continuous chain of bends and curve. You appear floating down a beautiful lake all the way; every twenty yards or so you turn a sharp, corner, and, lo! a more beautiful spot than the last. These sharp turns are dangerous to careless steering, and require not only a keen knowledge of the river, but steady steering. If the steamer ran aground, there you might stay for days; for she is the sole disturber of the water, and the banks are but very thinly populated. Consequently the vagaries of this intoxicated engine driver caused considerable alarm to the captain and unbounded fright and horror to the passengers, who were mostly ladies — about 18, I hear — and who got entertained in a manner they did not expect in this their trip up the beautiful Hawkesbury. The captain could not steer and manage the engines, small as the vessel was. The gentlemen there were nervous— besides, they were landsmen in every sense, and understood neither ; besides, the help did not appear very drunk on starting. He had the signs of licker but he had a bottle of brandy by his side, and a frequent application of his lips to this soon began to tell upon him. The first intimation they had of this was when, the captain politely desired him to 'clap on a little more speed.'; He turned it on with such a will that they had sharp work to clear the corner in safety. The captain expostulated, and said 'slower’, whereupon he nearly stopped the engine, and they scarcely moved through the water. By-and-by the captain mildly remarked a little more speed-would meet the wishes of the company better; hearing which the engineer sprung up, saying they didn't know what they wanted. He clapped on full steam, and the little boat positively flew up the river, emitting ever and anon an unearthly screech. This screech soon became a duet, for the fellow seeing the alarm around him, joined his voice to the whistle, and enjoyed amazingly the state of affairs. He kept possession of the engine, and the captain dare not leave the helm.

The ladies began to scream, the scenery was forgotten, terror and alarm took possession of all, and confusion reigned triumphant* ' Ye want speed do ye ? I'll give yon speed; I'll race the whole wurruld. Whoop ! twenty to one on the 'Florrie.' Look out for the banks, Cap'n.. Ha ! ha ! Isa ! be me sowl, but yo'll run uz aground if ye don't look sharp, an' thin tbira lovely crafchers forrard'll git drowned.

Och I sura 'twould amaze yiz,

How one Misther Theseas,

Desarted a. lovely young lady iv ould,

On a dissolute island

All lonely and silent

She sobbed herself sick as she sat in the cowld, '

“Take care Capt'n. Begorrah ye nearly done for us that time ; faith I never thought ye war such a poor steerer.- Its soon ye'll have us all on a “Dissolute island” if ye don’t take care. But I'm not a miserable ould hathin. I'll not desart the ladies. I'll stick be ye darlings.'

Here the drunken fellow gave a long wink and leer at the crowd of terrified females and continued his song. The echos on the many hills around caught up the refrain and threw back the discordant sound in many voices. Presently he got tired and appeared to be dozing, and a consultation was held on board as to the best means of ensuring the safe termination of their journey. It was decided that the man should be taken from his present position and safely bound aft. This was quietly arranged, and two gentlemen were told off to bind the unruly delinquent, and then take his place under the captain's orders. It was a very easy arrangement, but scarcely so easy to do as to say. No sooner did they lay their hands on him than he sprung up and soon laid them both on the deck.

‘Ha! ye divil's imps, would you take the engineer from his duty. What d'ye mane, ye pair iv igaorent savages be layin' yer claws upon rne ? Begorrah ! if ye attempt to get up from there I'll throw you both into the say. Where 'id ye be ye pair of lawyer's clerks — process servers may be for all I know, where 'id ye be, ye miserable haythins if ye tuk me from the works ? Stop yer screetchin ' he added, angrily, turning to the ladies, who were clinging together screaming, ' Ye set iv paycocke, or I'll blow ye all up, every one iv yez. Begorrah! I'll have ye in the nest world afore ye can say an ' Ave' if ye go on screetchin, ye unruly numbers iv society. I think ye've all come on boord drunk!’

Thus the up trip was made, the steamer arriving at the end of her journey a good hour or more late, where the passengers were received by ‘Paddy ' the whip, on the bank. If the waiting had cooled his horses and his feet it had warmed his temper, for he was in a very fiery mood, and made his horses and passengers suffer in consequence. The excursionists, sightseers, and pleasure seekers will not forget their visit to the Hawkesbury in a hurry.

The intoxicated engineer was brought up in Sydney and accused before a jury of his 'countrymen, of riotous behaviour, being drunk and incapable at his post, and of endangering and threatening the lives of 'so many of her Majesty's subjects. But these enlightened body of men found a trace of spite and animosity on the captain's part, and the worthy engineer was discharged, leaving the court with an aggrieved air, Verily, trial by jury is a wondrous and fearful thing. Justice is Hindi and law is as uncertain a thing as a woman's mind, of betting a hundred to one on the favourite.

We all watched the engineer's every move with expectant delight, trusting to see some drunken vagary, but we moved uneventfully down the stream, passing from one bend into, another, each beautiful enough for fairy land. The banks on both sides were almost continuously edged with the graceful weeping willow, their dropping branches trailing in the water.' I have never seen any scenery in Australia to compare in the remotest degree with that of the Hawkesbury. Nor had I connected any such grandeur with the name of Australia. Take it where you will, the river is splendid? On one side a steep hill rising immediately from the water's edge, covered with lovely tree-ferns, cabbage-trees, large trees covered with brilliant scarlet blossoms, another yellow, a third pure white* with here and there a huge grey rock showing. On the opposite bank, about a hundred yards of level ground, upon which a homestead, perhaps, is built, then the ground gently rises into a hill, with more and more behind. Sometimes you get a glimpse far away up a beautiful glen, with little, and large hills rising on every side. This goes on all the way down.

By 1 o'clock we stop at Wiseman's Ferry, and see the telegraph wire and Sydney-road going up the hill. There stands the ruins of the old church, roofless, doorless, and all gone the way all things earthy, excepting the walls, it is built strongly of stone, so possibly the walls will stand till the stones are taken away. Within this church is a vault, also roofless, wherein lie the remains of Mr. and Mrs. Wiseman, and others. No more. The leaden coffins lie on their ..exposed to view and the weather. I wondered if really no person was left with sufficient Interest in these coffins to cover the vault, and so let them rest is peace. As we stopped at the stone wharf that Sabbath day, the place looked one of silence…

Wisemans Ferry, Hawkesbury River, N.S.W. Image No.: c026780132, from Album: Photographs of Sydney and New South Wales, ca.1892-1900 / N.S.W. Government Printer, courtesy State Library of NSW.

Old Church, Wisemans Ferry, Hawkesbury River by John Black Henderson (1827-1918) St. Mary Magdalene's Church (Wisemans Ferry, N.S.W.). Image No.: a1528498, courtesy State Library of NSW.

…was the dip of the' puntsman's oars and a Voice as he sang at his work. I thought it a beautiful picture as I watched his form bend with the strokes, and his punt move on. The horseman got out, and after a friendly leave taking, went up the opposite bank, had the punt cams towards our side. I pictured the man judging partly by the thin quavering voice— a little old shrivelled man bent with his work, but happy and content. I was envying him his disposition, when the punt drew near, and I saw the man was young, with a face swollen and distorted either with drink or insanity. He began cursing and swearing at the unfortunate captain, who really seemed a butt for all their anger, and flew to the rope vowing to cut it adrift as we were Secured a yard or so more to one side. He soon cooled down and began to make himself more pleasant by ridiculing our steamer's build, &c. He came on board, and depreciated every particle of her from the wheel down. This party's name is 'Jack’ and he has plentifully bedaubed the fence with hid name and initials in tarry letters. He became quite friendly with us, and volunteered to show a trial and exhibition of his pulling capabilities This he quickly did by getting into a boat and pulling strongly Up the river, crying out as he did so, 'There's Bush for you. Ha ! Laycock, where are you now? Here's Wiseman's ferry style. Here's muscle. Come on Trickett. Come on, be beaten by Wiseman's ferry. Heap's Hanlan.’ As he swept by he glared at me, inquiring ' what I thought of Wiseman's ferry style.' We all cried out 'lovely.’

This favourable opinion he received pleasantly, and he informed us of the nature of the river, the fish it held, all particulars, saying sharks abounded 16 or 20ft long. I expressed astonishment, when he said he didn't care, he'd swim across the stream at A swinging rate this minute. The arrival of two gentlemen from the Inn put a stop to his executing this feat, and we put off, Jack waving us a good-bye, and assuring us of a welcome on our next visit. As we had no dinner we made a meal of biscuits, oranges and sweets; the captain's wife very kindly gave me an excellent cup of tea, for which I felt grateful. She would take no money for it, but said she intended to begin and have tea, coffee, or chocolate for any who chose to take at so much a cup ; this will prove an additional comfort to this most lovely trip. The elder gentleman got out some sketching materials and began to sketch some of our party, very soon I followed his example and I was, glad to see their neglected blocks and pencils come out and be used. Thus example was better than preaching. The younger fellow-passengers in passing bowed; and we were soon, like most travellers in a small space, upon friendly terms.

Although Wiseman's Ferry looked uneventful quiet and peaceful, it sees some funny scenes at times. For example, a few days before a travelling Bible distributer had come to the river's bank with a buggy full of Bibles. The buggy_ was drawn by a horse that had had no drink for over 24 hours. (This treatment of the poor animal seems at variance with the load on the baggy.; Upon seeing the water it rushed into it and was drowned. The dismay of the owner was extreme, as he saw his possessions swallowed up by the water. He called upon Jack to help, but his ludicrous antics and words caused Jack to be powerless of anything but wonder at himself. The buggy had been rescued, and a few of the Bibles, the missionary had them all spread out on the grass in the orchard of the hotel, in the sun to dry, and was kneeling in the centre, crying and praying, asking the Father to come down and get him out of his trouble. Then he-, would sit down, hugging his knees up to his chin and stare stonily before him, crushed with sorrow. Again he would pray and cry. He diversified this by going- over his books turning and straightening them. He had been like that for the last three days, sitting helplessly crying aloud upon the Lord-to come down and help him, apparently forgetting that God helps those that help themselves. These fellow travellers of ours had subscribed .£2 10s towards his relief and gave it to him, but he still sat like Niobe of old in tears, and refused to be comforted. I have often wondered if he is there still, or if he has procured a horse to take his buggy, Bibles, and self back to Sydney. We still sailed on, the banks on either side still as beautiful; they widened as we reached the mouth, and the foliage upon the hills grew darker.

At last we turned into Broken Bay, and we looked an admiring farewell at the beautiful river behind us.

I had been often wishing to visit the Hawkesbury, for I had heard two opposite opinions as to its claims for beauty: one was the laudatory encomiums of Anthony Trollope ; the other the condemning, disappointed opinion of a whilom friend, also an author and a traveller. But then he very naively remarked that his mode of travelling was rougher than he expected, and the creature comforts offered not up to his expectations or custom. He thus stood a living example that he saw through his palate, and proved the savine true that man may be governed by his stomach. He certainly has more of the animal than spiritual in his composition, else he never could have passed so much of the beautiful in nature without acknowledging its power. We stopped, at the inn at Newport all night; in the morning drove along the lovely road into Manly Beach, passing the poor old Collaroy lying high and dry up on the sands near Narrabeen Lagoon.

The country around was brilliant with the bright hues of wild flowers at this season. The stately cabbage tree waved its fan-like leaves, and a flock of black swans were visible on the waters of the lagoon. A wallaby hopped across the road, much to the children's delight. We took the steamer at Manly, and so home, sunburnt, tired and happy and as Buttercup sang; ' Not a penny in our pockets, la-de-dah !' This trip I would urge upon the notice of youne people, shut up in the city at business all the week, and highly recommend it. You could leave Sydney by the 9 o'clock train for Richmond on Saturday morning j on arriving there take Powell's coach to the Kurragong, dine there ; go on to Windsor by the train, sleep all night there, down the Hawkesbury on Sabbath morning, and back in Sydney on Monday morning by the first boat from Manly in time for office, school, or shop. The probable expense would be between £3 and £4 possibly less. A Round Holiday Trip. (

1882, December 30).

Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 - 1931), p. 6. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article108000733

Michael Maher, the former engineer on the steamship Florrie, was summoned, by Mr. C. E. Jeannerett, the owner of the vessel, for having, on the Hawkesbury River, on the 30th September, by drunkeness, so neglected the engine of the vessel as to endanger her. The vessel was at Newport, Pittwater, on the 30th September, having onboard the Hon. W. A. Brodribb and eight other passengers. The speed of the vessel was very irregular, sometimes being very fast, at other times only two or three knots an hour, and occasionally the engine stopped working ; at times there was only 40lb. of steam, and at other times there was 70lb. ; the engineer was observed to frequently go up and down from the engine-room to the deck ; a stoppage was made at Wiseman's Ferry, and as the passengers after going ashore came aboard the engineer was found lying on the deck helplessly drunk. The party were going to Sackville Reach, but a consultation was held, and it was decided not to proceed until the services of another engineer were obtained. The passengers stayed at Wiseman's Ferry that night, and next day an engineer named G. Brooks was engaged to look after the engine of the vessel. The prisoner was committed for trial. Bail was granted, the prisoner being required to enter into his own bond of £80, and to find two sureties in the sum of £40 each. WATER POLICE COURT. (

1882, October 10).

The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 5. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13524784

October sittings of the Metropolitan Quarter Sessions commenced yesterday, before Mr. District Court Judge Josephson, Mr. I. J. Healy prosecuted for the Crown. The only case of importance was one in which a man named Michael Maher was charged with endangering the safety of the steamer Florrie of which vessel he was the engineer, and the passengers on board of her, while on a passage from Newport, Pittwater, to Wiseman's Ferry, on the Hawkesbury River. Not withstanding that the evidence was very strong against the defendant, the jury found him not guilty, and he was discharged. NEWS OF THE DAY. (

1882, October 31).

The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 7. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13527380

Death of the Hon. W. A. Brodribb, M.L.C.

[By Telegraph]

From our Correspondent

Sydney. Wednesday.

The Hon. William Adam Brodribb, M.L.C., of New South Wales, is dead, aged 77. The deceased gentleman, who was the son of an English attorney, was born on May 27th, 1809, and came out to the colonies when only 7 years old, arriving at Hobart in 1816. He came to New South Wales in 1836, and at once engaged in squatting pursuits, being one of the pioneers of the Murrumbidgee, establishing a cattle station in the Maneroo district, and subsequently a sheep station near Gundagai. Thence Mr. Brodribb proceeded to the Goulburn and Port Phillip districts, and he there embarked upon an eventful and important exploring expedition in Victoria, which resulted in the opening up of the Gippsland lakes and the formation of the port now known as Port Albert, and named by his party. After many similar exploring expeditions, marred by much difficulties and hardship, Mr. Brodribb returned to New South Wales and again engaged largely in squatting undertakings. He crossed the Australian Alps with a herd of cattle and horses and a flock of sheep, and established a station at Wangaratta, but sold out on the approach of free selectors and went to Victoria, residing at Brighton, for which electorate he was returned to Parliament. He then went home to England, and returning to the colonies established some stations in the Lachlan district, New South Wales, somo of which he retained until his death. During a second visit to England Mr. Brodribb was elected F.R G.S. and F.R.C.I., and proved instrumental in bringing about some important reforms in the wool trade in association with Sir Daniel Cooper. Coming back to the colonies, Mr. Brodribb purchased Buckhurst, near Sydney, in 1876, and remained there till he died. He was called to the Legislative Council of Now South Wales in 1881. Death of the Hon. W. A. Brodribb, M.L.C. (

1886, June 2).

The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 - 1947), p. 5. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article174701998

Alfred Milson's holiday house, Milson Island, Hawkesbury River - Dr R.D. Ward, amateur photographer, on the veranda of Alfred Milson's cottage, Milson Island, Hawkesbury River- Digital Order Number: a282009 from Collection ; Millers Point, Sydney ; Residences at Hunters Hill, Milson Island & Nattai ; Ships, China, Eastern Light, & Parramatta, courtesy State Library of NSW

The Sketcher.

A Trip to Gosford.

Leaving Sydney by the 7.15 a.m. steamer for Manly, one discovers how pleasant and refreshing a trip down the harbour may be on a crisp September morning, and regrets on reaching Manly that there are but some 15 or 20 minutes allowed for satisfying the sharpened appetite before the Pittwater coach gets under way. Bowling round the corner, the team, fresh as two-year-olds, takes us at a merry pace along the level road, past the lagoon, and into the bush, continuing amid rock and scrub that grows so prolifically in this sandy soil. A fairly good road gradually ascends for several, miles, the left being a mass of rough broken country, and the right, some high ground shutting us off from the sea, till presently we come almost on to the sea-shore, and every hill we top gives as a view of the continuous bay and headland coast-line stretching ahead for miles.

After some six or seven miles, descending a sharp decline, we almost ran on top of the Collaroy, high and dry on the beach. The bizarre object startles one as it is so absurdly out of place; but the Company's balance sheet still reckons her an asset.

The road seems to end here, and the coach enters upon a level strip of sward overawed by a straight range of steep, rocky hills, with a cabbage tree on top, limned against the sky. Here, meeting the fresh north wind that lifts the horses' manes, the leaders put their heads down and stretched themselves for a canter. I had been especially directed to select this route on account of the beauty of its scenery, so closely resembling, at times, that of the Rhine. But although one part of Europe may frequently recall another to the recollection, yet in Australia nature has assumed such distinct characteristics, that all comparison is rendered out of the question, nor could any effort of the imagination convert the old stone ruins on the rise at the end of the flat into the remains of some castle of romance. We could not elevate oneself above the conviction it was but a settler's or free selector's home-stead. Recently the land about here was sold, fetching prices up to £10 for quarter-acre blocks.

A little further on we entered Narrabeen Lagoon, when the water came over the bottom of the coach. For three quarters of a mile the coach struggled along through marsh and water, not daring to stop lest the wheels sink in the sand. However, it is understood the Government will call for tenders next month for the construction of the bridge. Coming out of Narrabeen the coach passes round a finely formed hill abundantly clothed with tree and fern, including quantities of the Burrawang species. On the left arises a cleared eminence with two red cattle; beyond, a half-cleared flat, with a mass of low gnarled gum trees in front, through which the road leads ; on the right are some stretches of white sand, with a reddish-brown bluff rising above, and splashes of spray dashing up against it ; a few light clouds above break the sunshine. It is a good specimen of natural Australian landscape, and these are to the picture the finishing touches of the artist's master hand. As a centrepiece of such a scene, none but a painter knows the value of a lumbering coach and four, axle deep in water, slowly dragging its way along.

From Narrabeen to Pittwater is a succession of hills and gullies, the views, and retrospect from each becoming finer and finer. The aspect of the coast, which is now continuously in sight, suggests somewhat the snapped off red clayey cliffs of Devon ; while two or three miles beyond are seen the deep gorges among the hills that hide the lake of Pittwater. From a distance, the rugged boldness of the hills bear many of the characteristics of mountainous parts of the Black Forest, although when close the vegetation and the general appearance of 'unfinishedness' effectually dispels the illusion.

Presently we approach a promontory with rounded top and sides, smooth shaven like a lawn, and interspersed with scrub like the soft buxom furze of a Cornish hillside. It is remarkable besides for its massiveness, and one feels on reaching the summit as though he had overcome one of the obstacles of life. At length, reaching the eminence above Pittwater, we take our last view of the ocean with its half score of white sails dotting its wide surface in an aimless sort of way, and call each other's attention to the dignity waves can assume as they come rolling in with a slow lazy sweep and curl and break on the curved sandy stretch that connects the protruding frowning headlands. Turning inland, we enter, as it were, the top rim of the basin of the lake, and suddenly come upon the loveliest spot between Sydney and Brisbane Water. On the left one looks down a gorge ever so steep down : down through the stems of several species of gum, ironbark, mahogany, forestoak, turpentine, and cabbage tree, their tops netted into a dense mass of foliage, their bases buried in a profuse overgrowth of fern, bracken, clematis, and the graceful burrawang, a species of palm-fern, while in the mid-distance between the tree stems one can trace the stream at the bottom. The scene is rich with the luxuriant beauty of a New Zealand pass. Coming round the shoulder of the hill, openings in the trees betray glimpses of the deep blue waters of the lake, while the scene stretches away beyond to the high enclosing hills, in all their deep colouring, like one of Conrad Martens' pictures.

A few minutes more, and the coach stops at the Newport Hotel, having accomplished the 14 miles in about two hours. At the waterside awaits the steamer Florrie. A little to the right, in a small bay, is another wharf, with a large house close by approaching completion, and destined for a boarding-house. As we steam out, we wonder which way we shall take, for the lake is completely landlocked by huge bluffs rearing themselves up above us like so many 'Ball's Heads,' and suffering rough jagged gorges to penetrate their way deep into their mass. In several places where the nature of the ground allows settlement, cottages and gardens and orchards have sprang up, and their beauty of situation renders one envious of the owners.

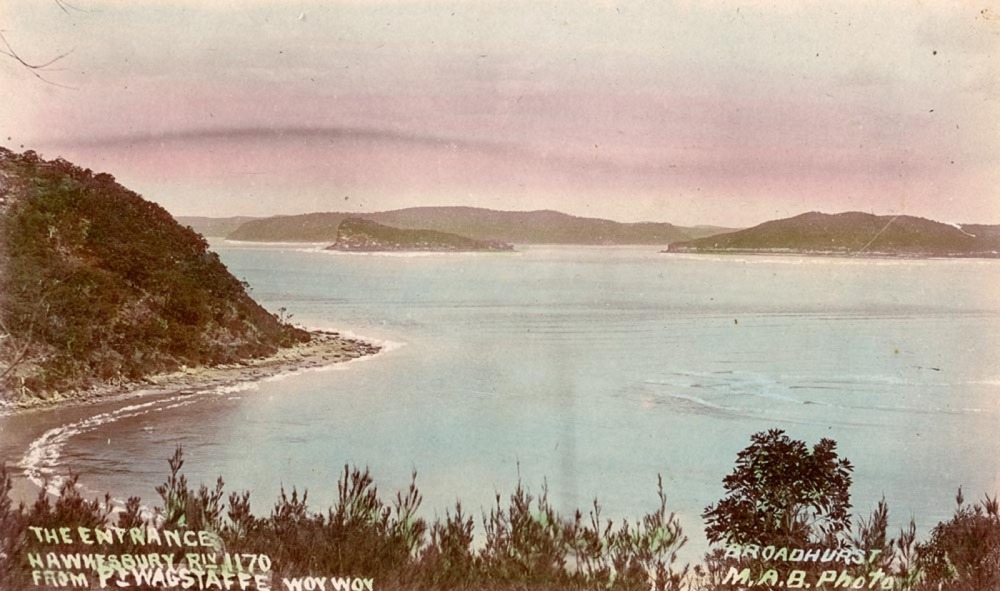

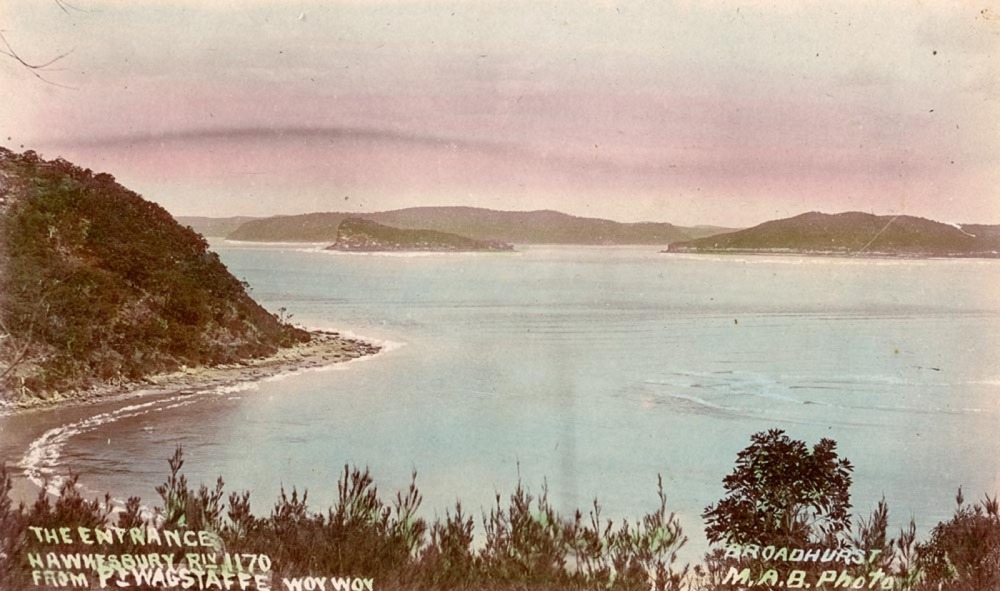

Bending to the right, we pass between Lord Loftus Point and Scotland Island, while far ahead, near the heads of Broken Bay, is seen the noble island, in shape like a couchant lion guarding the entrance as he faces it. Pittwater forms a magnificent harbour, and, undoubtedly, in due time its waves will reflect the lights of a grand city reared upon its banks. Its entrance, some three miles wide, is wondrously safe. Its waters are deep, absolutely sheltered from every quarter; and as to its size, would float the navies of the world. Pittwater is the southern arm of the estuary, Brisbane Water the northern, while between, straight in from the Heads, stretches westward the grand outlet of the Hawkesbury River, between two enormous banks. Few rivers can match its magnificence of debouchure, as the hills boldly approaching the ocean in all their pride of strength majestically deliver up the waters confided to their charge. At the Barrenjoey lighthouse, whence also a cable is laid to Brisbane Water, we come in sight of the entrance to the harbour, and as we cross have a full view on our left of the estuary of the Hawkesbury.

The entrance, Hawkesbury River, from Pt. Wagstaffe, Woy Woy from Scenes of Hawkesbury River, N.S.W. ca. 1900-1927 Sydney & Ashfield : Broadhurst Post Card Publishers Image No.: a105348, courtesy State Library of NSW.

Passing in front of the island, just under the lion's nose as it were, we approach the bar that spoils Brisbane Water as a seaport. It is thought that possibly by blowing up the half tide rocks by dynamite, as was done in Hobson's Bay, the unimpeded rush of water would carry away the sand bar. When the wind is blowing from the south-west the heavy rollers break right on to the bar, rendering it impassable. Before crossing one admires the singularly graceful contour of the high range of ground shutting us of from the ocean, while on the left the eye commands the still higher range that enclose the valley of Brisbane Water, and tempered as to its massiveness by that same deep colouring resting upon its sides that seems to belong to all the Hawkesbury scenery. Safely across the bar we begin to wind about with the river which is much too tortuous, for though numerous huts and humpies perch themselves upon the shore, yet the scene grows monotonous. One misses the rich fields and cornlands, the pasturages, and terraced vineyards that border the (in comparison) tame rivers of Europe. The hills and valleys in their form are beautiful enough, it is the same-ness of the vegetation, the everlasting, unchanging gumtree that tires the eye.

Mr. Rock Davis' building yard at Blackwall is the only place of interest passed on the way. One boat in the stream is near completion, and another is in process of building. Mr. Davis has been very successful with his boats, which, besides for their soundness and durability of make, are much admired for their grace-ful lines. He uses nothing but local timber. Several of the ferryboats in Sydney harbour come from his yard, and orders are tendered far in excess of his power to fulfil them. it is not very long since that he launched his first steamer as an experiment, and her arrival in Sydney at once gained a reputation for this yard, and at the same time proved the adaptability of the Brisbane Water timber for shipbuilding Just as one begins to grow weary and very hungry, our little craft emerges into the Broadwater, at whose far end, under the shadow of the hills, is discerned the little town of Gosford. Presently, on a point to our left, is noticed the first patch of cultivation. On the right, opposite East Gosford is Green Point, which was lately sold in allotments at such high prices. Drawing near Gosford, after some 25 minutes' run across the Broadwater, one's attention is attracted by the parsonage, with four Norfolk pines, admirably situated on a point. Farther round, lying between the hills that rise to a great height, on either side stretches back from the water the town of Gosford. Still to the left, at the extremity of the Broadwater, begins Nerara Creek, extending in a north-westerly direction. On the right, through East Gosford, runs Erina Creek, watering the magnificently wooded tracts lying between Gosford and the sea.

Gosford, situated on the bottom slopes of a hill, consists of one street, in which are located the substantial post and telegraph offices, the Police Court, the Mercantile Bank, three hotels (one being a fine two-storey building), some five or six small stores, and a score or so of dwellings. High up on the hill is the Public school, with an average attendance of about 80. The surveyed line of railway crosses the Broadwater, and passes up the valley some 200 yards from the main street Brisbane Water was but little known until the proposal to construct this railway to Newcastle gave it a prominence it never hitherto enjoyed, although being one of the oldest settled districts. But since being brought thus into notice it has been largely visited by interested speculators and business people, who have returned convinced that Brisbane Water will become something of a winter and spring resort, which, added to the fact of its possessing- many undeveloped capabilities, and being, more over, situated between Sydney and Newcastle, will render it by the time the railway is opened an important town.

Compared with other parts of the colony, Brisbane Water exhibits a lack of energy and enterprise. Its inhabitants, able to earn a fair and regular livelihood by wood getting, have allowed every other industry to fall into abeyance. Even the gardens and orchards, so well known in former years, are now unfenced and uncared for. Even the very homes of the wood-getters are, in most cases, without an enclosure, or, at the most, they grow but a few vegetables to suffice for their own needs. Yet the soil and the climate are well adapted for cultivation and growth, and no place enjoys so mild a winter. But to the visitor the dominant notion of the inhabitants appears to be that it is easier to let the timber grow of its own accord, and content themselves with cutting it when it has reached the requisite size. And these carters and timber-getters do not even attempt to grow their own horse- fodder, preferring to obtain it all from Sydney. To one who knew the place 40 years ago it is saddening to see its retrogression, and naturally one begins to seek the cause. In the early days many of* the best families of the colony either lived there, or owned property. Its natural beauty, fertility of soil, nearness to Sydney, and its accessibility (for in those days a short trip by sea was preferable to one in bullock waggons) rendered it desirable for settlement, and accordingly Brisbane Water acquired a reputation. But the first settlers soon found that timber getting was far more profitable than agriculture, hence, except in a few clearings about each homestead, no attempt was made to cultivate.

The value of the timber trade may be inferred from the fact that from Erina Estate alone timber to the value of £4000 was sold in one year, and from that day to the present timber getters have been, and are still cutting timber on the same land. But in process of time, as the country became more opened up, and sheep farming took the premier position in the colony's industries, then one by one the old families left Brisbane Water, leaving none behind but the actual wood-getters, lime-burners, fishermen, and their purveyors. And thus remained the district for more than a generation. Bat now a new era has begun. At the prospect of a railway it has bestirred itself. Trade has revived. One steamer for passengers alone makes three trips a week, and two steamers direct make each two trips ; a bank has established a branch, and stores and dwellings are in course of erection. Even the church shared in the general improvement, a bazaar having been held to provide funds for its repair, when £106 were realised. As a final evidence of a better state of affairs, the people themselves admit there is now more money than there used to be. To one who knows anything of country towns this confession means much.

As to the salubrity of the climate, there can be no question. There is no doctor there. Yet, although the population is considerable, the last resident doctor declared he owed his subsistence to surgical practice. The appearance of the school children is a living proof of the truth of the doctor's assertion. Sitting on the upper verandah of Campbell's Hotel, one begins by admiring the magnificent hill uptowering in front, hiding the westering sun, and ends with an inexpressible longing to climb to the top, a desire which has to remain unsatisfied till the next day. It is useful to go early, for the cool of the morning is absolutely necessary to enable one to tackle the climb. One has positively to cling to the hillside, but it is an exquisite hill, wooded with tall, straight trees, and carpeted with fern, and capped with rock, the very top being a broad, flat rock, charming for a picnic ground, superb hi its loftiness of site., exquisite as to view. Following a first instinct, one seats himself on the edge of the rock and hangs one's legs over. It is a sheer drop of 20 feet to a broken mass of gray lichen and moss grown rocks, lying cosily in a bed of soft green fern. On every ledge rock-lilies have found a foothold. The treetops are 20 or 30 feet below, and one looks over all to the south over the Broadwater, four miles long, with Gosford below on the left, and the tongue of land running far out into the lake, dividing East and West Gosford. Away over the Broadwater, one looks down between the line of hills that opens for the vision, over the flat scrubby land at the river mouth, over the blue waters of Broken Bay itself; one looks, Broken Bay with its lion-like island in its midst more conspicuous now than ever, across the bay with its single white sails, across to the sandy beaches of Barrenjoey, and to the high lands beyond that finally stop the view. Down at my feet lay a true Australian scene of untouched forest, and to the right, round the hill, sweep the graceful windings of Nerara Creek, across whose mouth runs a line of white posts marking the site of the railway bridge. This hill is the great feature of Gosford, being admirable hi every respect, and a remark in its praise always elicits a gratified smile. On the opposite side of the town, delaying the sunrise, is another range of hills even more lofty, but not so fine, either in form, view, or vegetation. West Gosford lies in the valley between. Leaving West Gosford, a walk of a mile or so from the Post Office brings us to semi-deserted, slowly dying East Gosford, once the chief town, where is the church, and formerly the steamer wharf. The church had been built in one town and the parsonage in the other, in order to allay their rivalries.

In East Gosford the structures are of wood ; but in the other town nearly all the buildings are solidly built of stone. Stone houses in a country town always impress a visitor. They take away the 'mush-room' aspect that distinguishes but too many country places, and evidence, on the part of the inhabitants, a faith in their town. Crossing over Erina Creek by the old punt, still ferried by the same old blind puntman that took me across 20 years ago, we made the best of our way over a horribly bad road (which, however, Government is about to reconstruct) for a couple of miles through low-lying land, bordering the creek, heavily timbered, and with a strong under growth. Having reached a considerable clearing, we are suddenly astonished to behold a ketch, apparently entangled amongst the scrub. The existence of a vessel in the bush reminds one of scenes in Holland, where one is so often startled to see lumbering Dutch crafts in full sail in the middle of a field. Frequently a sail is the only indication one has of the proximity of a canal. At the wharfs of Erina and Wyoming, on Nerara Creek, the ketches chiefly load with timber, laths, &c. The present activity in the building trades in Sydney renders lath-getting unusually lucrative, enabling a couple of boys to earn as much as £3 per week. Bundles of laths, delivered at the wharfs, are sold for 13s. ; formerly they fetched from 6s., and men were glad to get that sum. Beyond the wharf a short distance, ascending a slight eminence, we come to the site where formerly stood Erina homestead (the residence of Henry Donnison, Esq.).

The half-destroyed orchard and the homes of three or four woodgetters in the vicinity are all that remain to mark where once stood a huge and handsome dwelling, with a village comprising artisans of several trades. A ride hence in an easterly direction for some four miles brings us to the coast. Several clearings are passed on the way, in most of which still stand the lemon hedges and the fruit trees that were once a source of considerable profit, but all now apparently forsaken for the timber trade. At first sight one is led to deplore the utter decadence of energy ; but what I myself saw, and the testimony of the people themselves, proved to me that timber getting in this locality is a substantial and remunerative industry, nor does there appear to be any indication of its languishing. Years ago one heard of most of the heavy timber being cut, but the trade is actually on the in-crease. The soil produces wonderful trees, tail, straight, and solid like a ship's mast, and trees that five years ago were reckoned but saplings are now being cut for beams and rafters— aye, even for the piles for the Circular Quay extensions. The supply between Gosford and Tuggarah appears to be practically inexhaustible. The country is undulating and varying in its character from stony ridges and clayey flats to the rich loam of the brush or scrub land. The chief wood obtained from the higher ground is red and blue gum, red and white mahogany, turpentine, iron bark, stringy bark, blackbut, and forest oak. From the brush land, whence come the finest, logs, are derived the coachwood, maidens' brush, and ash. The brushwood is very beautiful. It is a dense jungle, semi-tropical in its character, and wrapped in impenetrable shade. Roads run hither and hither through its midst like avenues cut out of the foliage ; the gaunt grim stems of mighty trees rear themselves out of the undergrowth; here and there giant logs, moss grown, peep from out the screening bush ; clustering vines and clambering clematis run from shrub to shrub; the lawyer vine weaves everywhere an almost impassable net ; Deep, mysterious fissures to the right and left reveal the wonders of vegetation. This is the very home of the fauna tribe, which seems to have attained its perfection, and the groupings of fernery present a positive artistic arrangement. The tree-fern, and also the much-sought-after Bangalow species grow in abundance. In the profusion of wild beauty and overbrimming luxuriance it seems to laugh at the puny attempts of art, and in the dark rivulets that are no sooner seen than lost again, one thinks he has found the dryad of the scene.

Ascending again, we presently pass two prosperous looking cottages, and come within sight of Tarrigal lagoon, then the ocean beyond, and some half-mile distant, on a' high bluff, the residence of Thomas Davis, Esq. Below his house, in a little bight well sheltered from every wind by Point Willoughby, axe the sawmills, building yards, and wharfs. The mill is not at present working, on account of new machinery being erected ; but the good order of the different departments, the constantly arriving teams, and the business-like aspect of the establishment greatly impress a stranger with the importance of the timber trade. D uring the whole of Mr. Davis's experience, but one mishap has occurred, when the schooner Wonga Wonga was blown on to the beach and wrecked, and yet this occurred through an accident that might have been easily prevented. The spot where stands Mr. Davis's house one would suppose to have been chosen from the whole coast for beauty. It commands a view of sea and coast line, over the fields on the hillside, over the lagoons, and the deep woods, away to the hills inland. Returning, we took a road that led us past the lagoon and Womberall Lake, meeting the Tuggarah Beach road. This led us through more magnificently timbered country, even richer in variety, and taking us likewise through much land adapted for agricultural settlement. It has been so long-supposed that coal was to be found in this district that Mr. Davis put down a bore at Tarrigal to prospect. He sank as deep as the old-fashioned bore would allow, and obtained such encouraging indications that he hopes to have it properly tested. The value of such a discovery, close to a place of shipment, is beyond estimate. A ride of some seven miles northward from Gosford, past Wyoming, along the surveyed railway track, brings us to Blue Gum Flat, another settlement that is developing in activity. At every turn of the road one encounters horse and bullock teams, for the timber on the flats beyond Blue Gum Flat is considered some of the finest that Brisbane Water produces. The road from Gosford, as might be supposed from the travelling of these teams, is execrable, although in many parts truly romantic. There is one grand avenue where the trees on either hand rear themselves straight up 100 to 150 feet, hiding their stems for 30 feet in brush, and burying their roots in fern. As we rode slowly along, the forest seemed to acquire that majesty that the American poet Bryant loved to tell of in his own great forests. It is grander even than the noble cuttings in the Black Forest. In the gladness of the morn, every bird seemed to have given itself to song, and ever and anon above the rest was heard the clear rare note of the tiny bell-bird. The road is hilly, but the view circumscribed by reason of the bordering growth of wood. In this direction is Wyong, where was recently found three distinct layers of coal de-posits, and for the purpose of working which Mr. Allison is reported to have gone to England to float a company. Not the least pleasant time in Gosford is the evening, when the environing hills early hide the sun, and lengthen out the gloaming. To drift about on the lake is full of that charm that has awakened poetry in every age, and as the hills draw down their shadows for the night, the masses of dark outline towering above the glimmer of the lake recall the solemn stillness of night upon Lake Como where one feels with unaccountable awe, that it is but the darkness that veils the presence of the Spirit that rules the destiny of life. SYDNEY. The Sketcher. (

1882, September 30).

The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 - 1912), p. 542. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article161926095